The arrival of Benito Mussolini

The beauty and majesty of Palazzo Venezia, combined with the strong patriotic value acquired during the First World War, captured the attention of Benito Mussolini, who transformed it into an essential element of his propaganda

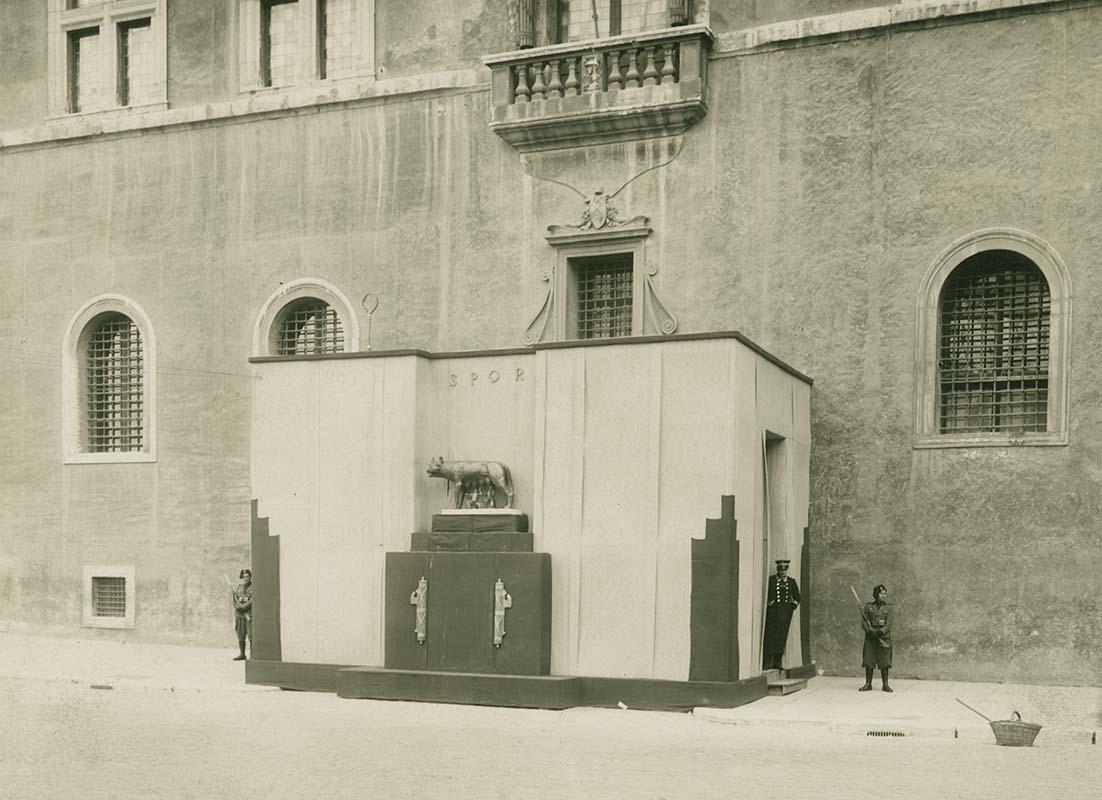

Palazzo Venezia, located in the heart of the capital of Italy and by now one of the symbols of the Italian victory in the First World War, fascinated the leader of the National Fascist Party, Benito Mussolini. After the exhibition dedicated to the works returned from Austria, he declared his intention to make the building the representative seat of his new government. As a master of communication, Mussolini had understood the potential of the building and in particular of its balcony which, directly overlooking the square, allowed him to gather oceanic crowds in front of him.

Mussolini reserved the Barbo Apartment for himself and the monumental rooms, leaving the Cybo Apartment to the museum and the Palazzetto. Curiously, the subdivision of the spaces that had characterised the life of the building between the second half of the sixteenth century and the end of the eighteenth century, when it was simultaneously the residence of the cardinals of San Marco and the ambassadors of the Republic of Venice, was fished out again.

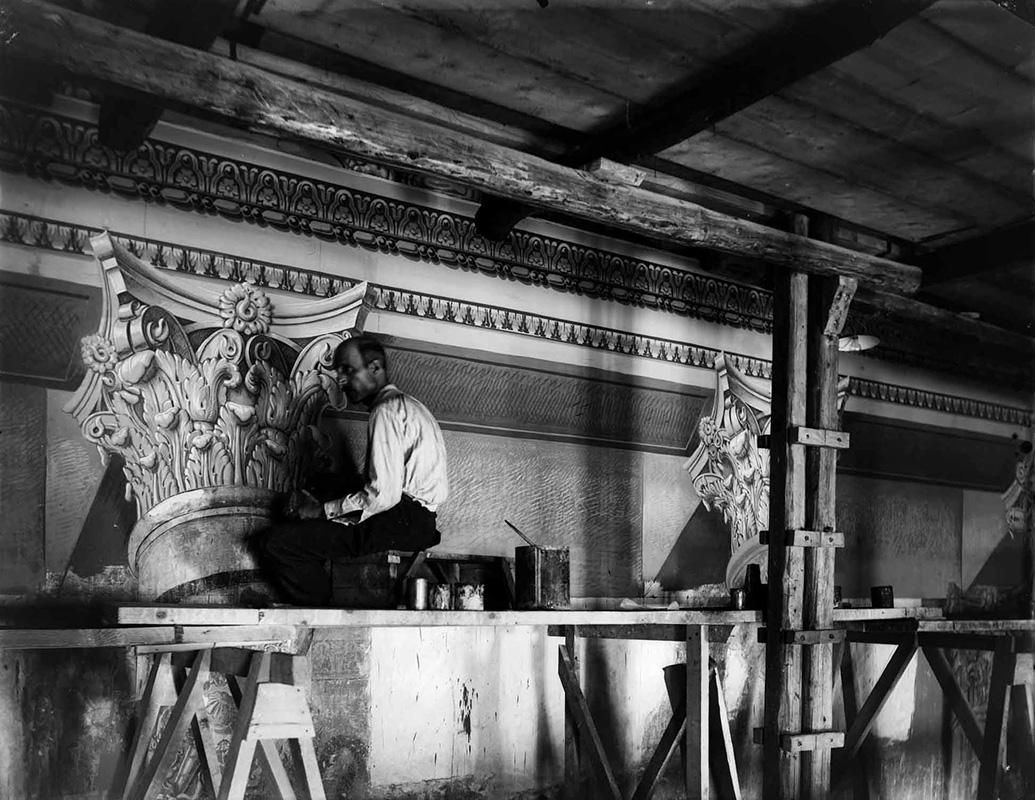

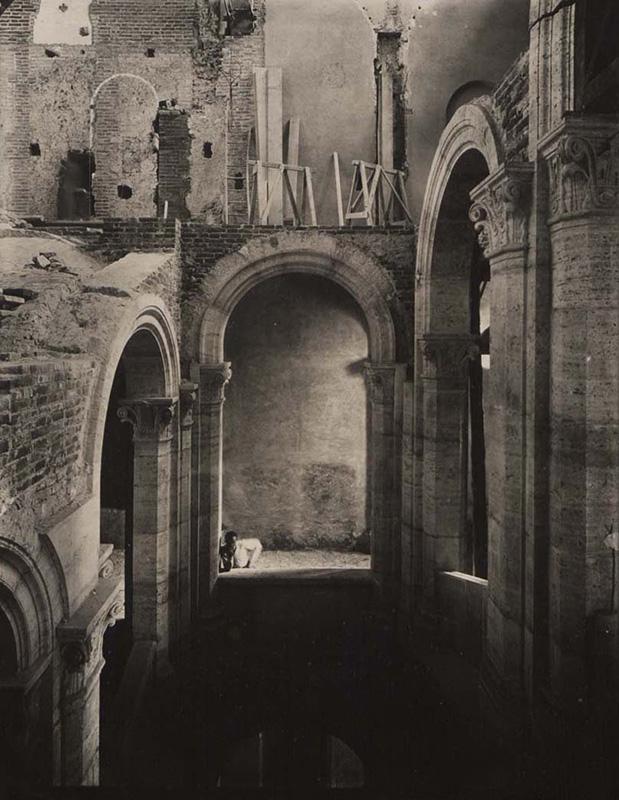

Palazzo Venezia underwent an intense restoration campaign in 1924, in order to fully fulfil its new government function. The works, completed in 1936, deeply affected the decoration and also the layout of the building: this is evidenced by the large reception rooms, the final arrangement of the Barbo Apartment, the adaptation of the second floor to Mussolini's private apartment and the Grand Staircase, built in Neo-Renaissance style. The work was the responsibility of a special committee: chaired by Giuseppe Volpi di Misurata (1877-1947), for the technical aspect the committee availed itself of art historians Corrado Ricci and Federico Hermanin, of architect Armando Brasini, at the time artistic director of the Vittoriano and of the Venetian engineer Luigi Marangoni (1872-1950).

Mussolini, who had been present in the building on an occasional basis since the mid-1920s, moved there permanently on 16th September 1929. Thereafter, the building became a part of the regime's politics and diplomacy on a permanent basis, among other things as the setting for official visits by foreign heads of state.

A photographic campaign of 7th May 1938 portrays Mussolini with Adolf Hitler and his Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop at his side, whilst greeting a cheering crowd from the balcony of the Sala del Mappamondo.

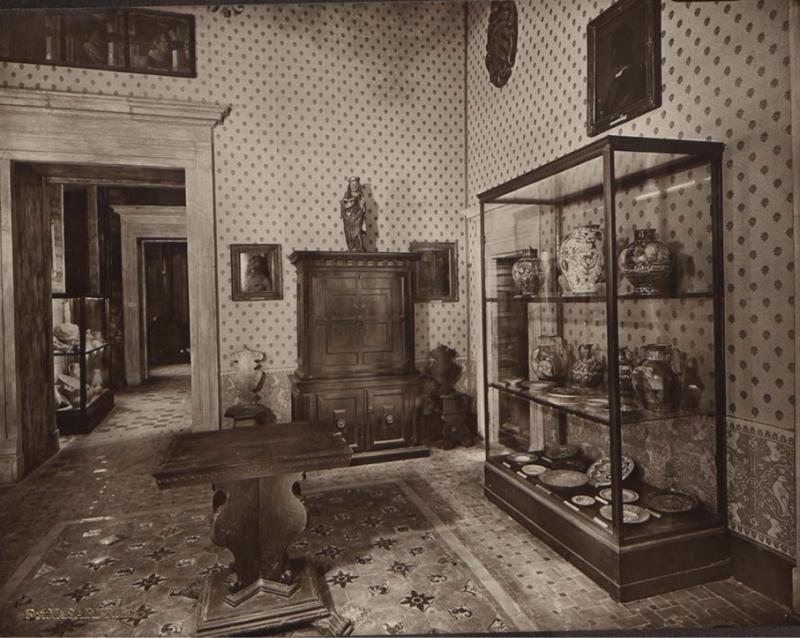

The rise of Mussolini went hand in hand with the development of the museum's artistic heritage. The collection willed by George W. Wurts (1843-1928) and his wife Henrietta Tower (1856-1933), a wealthy American couple who had chosen Rome as their second homeland for several decades, dates back to 1933.

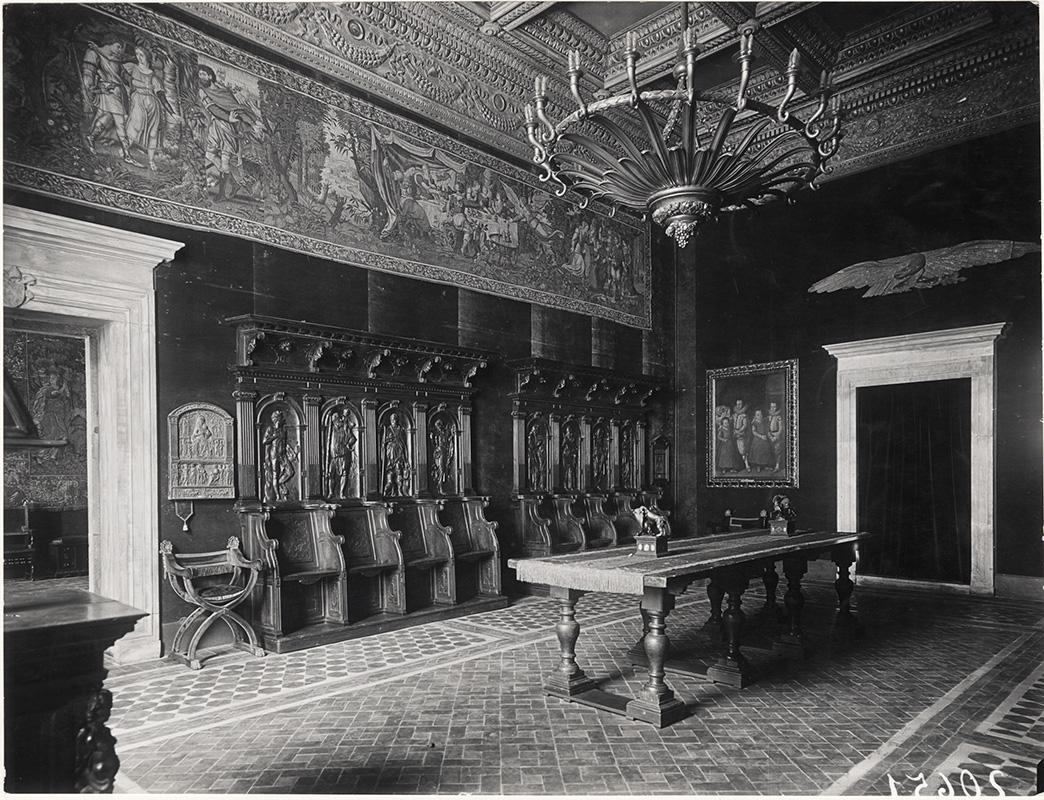

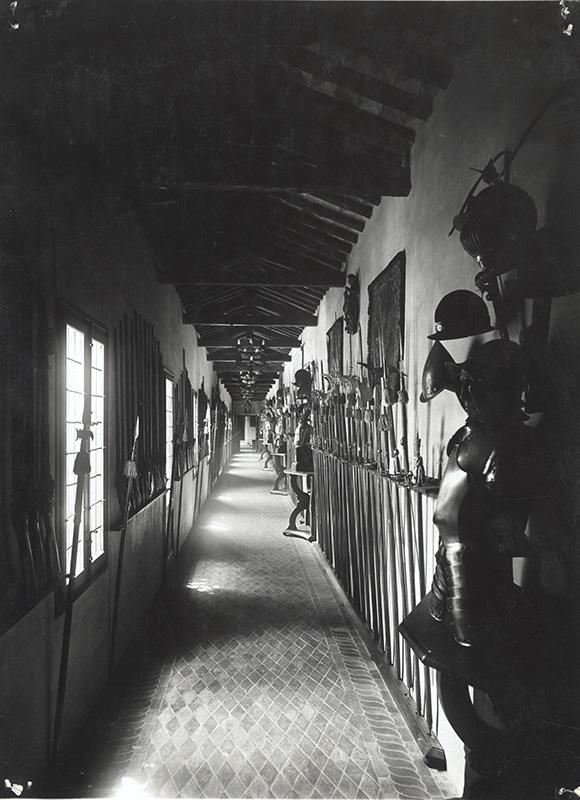

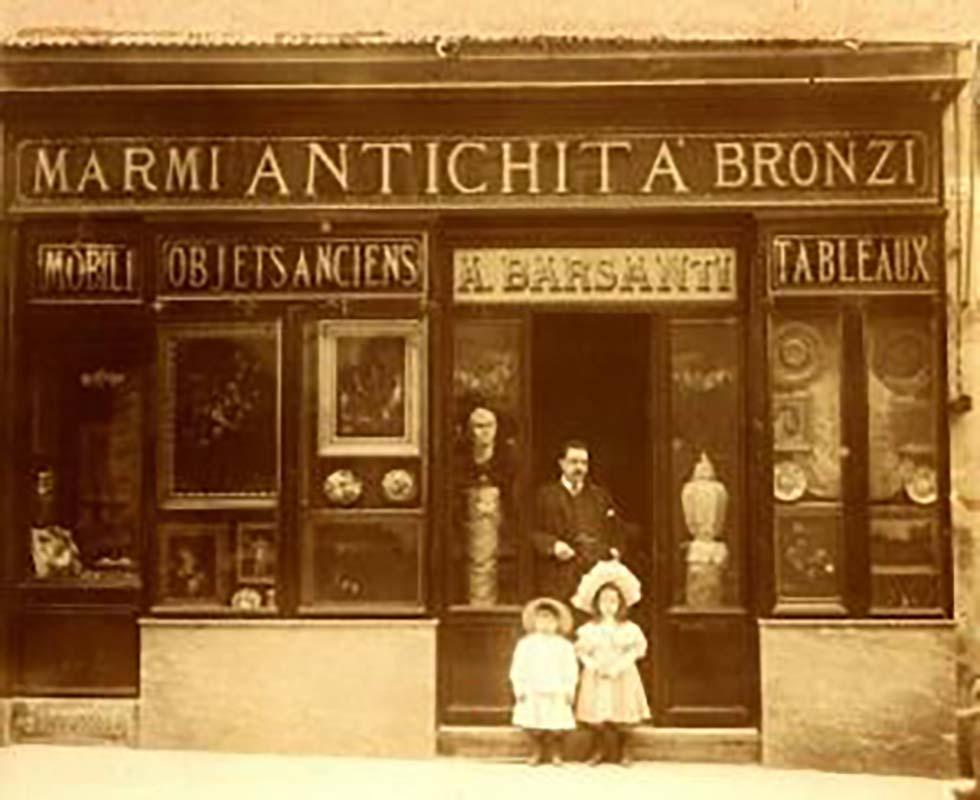

The following year, 1934, was the turn of the collection of one hundred and nine ancient bronzes set up by art dealer Alfredo Barsanti (1877-1946), in this case donated to Mussolini by a group of industrialists. In 1936, Federico Hermanin was able to complete the preparation of thirty-four rooms, which from the Cybo Apartment extended up to the Palazzetto. However, the rooms were never opened to the public: in fact, they remained the exclusive prerogative of Mussolini, who loved to bring there his most important guests to show the treasures inside.

On the afternoon of 24th July 1943, Palazzo Venezia hosted the last meeting of the Grand Council of Fascism. At the head of a large U-shaped table in the Sala del Pappagallo Benito Mussolini sat down, with the twenty-eight convened around him. Founded in 1922, the Grand Council was the supreme organ of the regime. Although devoid of binding functions, in the early years of fascism it had played an important role, if only to acquire knowledge of the opinion of the various party currents, but over time it had ended up withering away. The last convocation dated back to 1939: since then Mussolini had made his most important decisions without consulting it, fearful of confronting his own hierarchs.

The sudden awakening of the Grand Council was due to an agenda presented by the President of the Chamber Dino Grandi (1895-1988). At that point the fortunes of the war appeared to be compromised: on 10th July the allied troops had landed in Sicily, without finding any noteworthy resistance, on the 19th the Anglo-American planes had bombed the capital. Through his agenda, Dino Grandi, with moderate tendencies and inclined towards a truce with the allies, intended to deprive Mussolini of his supreme powers and, at the same time, to steer Italy towards exiting the disaster of the Second World War.

The outcome of the ballot was known at 2.30 am on 25 July. Of the twenty-seven voters, nineteen voted in favour of Grandi, nine against, one abstained. Later, still on 25th July, Victor Emmanuel III (1869-1947), having removed all Mussolini’s powers, had him arrested by the Carabinieri, to then broadcast the news via radio at 10.45pm. But the fall began exactly here, in Palazzo Venezia.

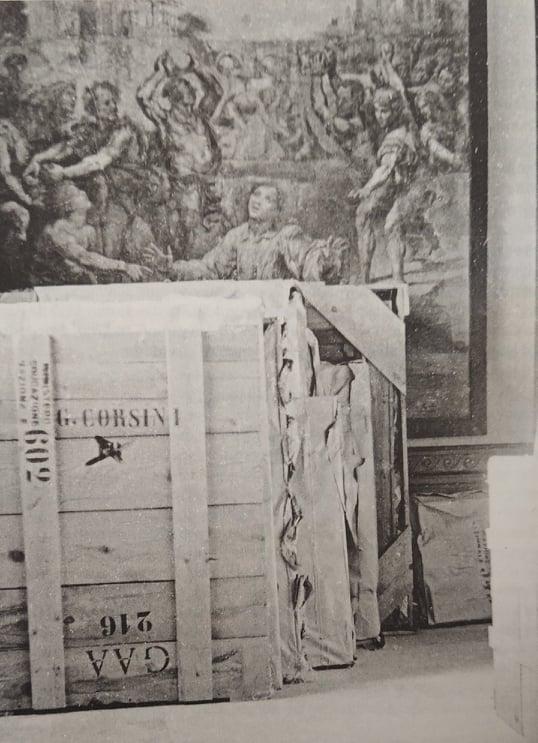

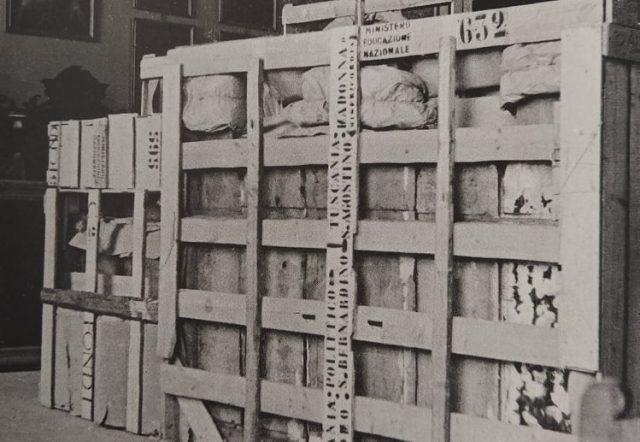

Now that the period linked to Benito Mussolini had ended, Palazzo Venezia continued to play an active role even during the last, dramatic months of the Second World War. On 12th November 1943, the Italian authorities managed to bring to a successful conclusion the negotiations begun in August to safeguard the most relevant assets of the national artistic heritage inside the Vatican. As had already occurred during the First World War, Palazzo Venezia became the main collection place. On 20th and 21st January 1944, two rooms of the building hosted a temporary and objectively extraordinary exhibition, at the end of which the masterpieces were transferred to the Holy See.