The foundation of the palace

The origins of the palace, linked to Cardinal Pietro Barbo, later Pope Paul II

The history of Palazzo Venezia begins with Pietro Barbo (1417-1471). Barbo, born into an ancient and noble Venetian family, decided to pursue an ecclesiastical career when Cardinal Gabriele Condulmer, who was his mother's brother, became pope with the name of Eugene IV (1431-1447). Pietro's climb up the ecclesiastical hierarchy was also rapid for this reason: the appointment as cardinal deacon occurred in 1440, when he was only 23 years old. From an early age he showed a passion for architecture and art, which led him to put together a remarkable collection, mostly of classical objects. In August 1464, Pietro was elected pope and took the name of Paul II (1464-1471).

The area corresponding to today's Piazza Venezia, the arrival point of Via Lata, the urban stretch of the Flaminia now known as Via del Corso, remained on the edge of the medieval and sparsely populated city until the middle of the fifteenth century. Dominated to the south by the Capitoline Hill, the area’s most prominent centre was the venerable Basilica of Saint Mark the Evangelist: built in the 4th century and rebuilt several times in subsequent periods, San Marco represented the gathering point of the city’s “colony” from the Veneto region.

As cardinal, Pietro Barbo took over as titular of San Marco in 1451. He soon decided to rebuild the adjacent building from scratch, judging it to be excessively small and modest. The start date of the construction site dates back to 1455, as evidenced by some commemorative medals, still in the museum's collections today.

As soon as he became pope, in the summer of 1464, Paul II resided inside the Vatican palaces. However, he soon decided to move to the Palazzo of San Marco, which then began a new phase. The relaunch of the construction site is attested by a second medal, minted in 1465, now exhibited in the Sala del Mappamondo: the palace, destined to worthily welcome the new status of papal residence, would become one of the largest and most important buildings in Renaissance Rome.

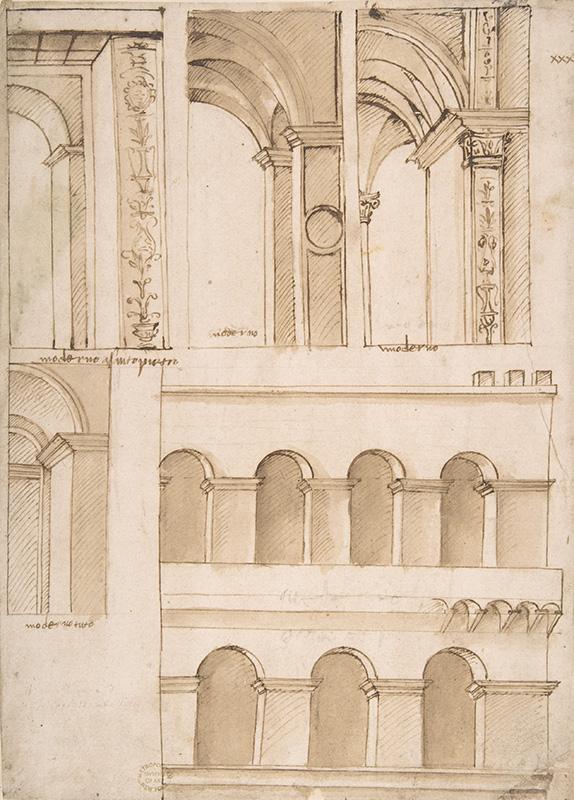

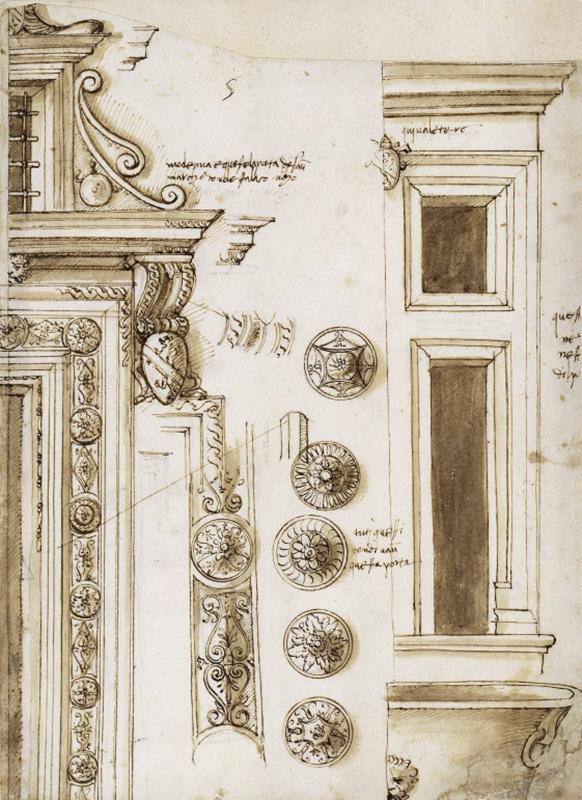

The issue is still widely debated. Some attribute the project to Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), the great humanist and architect of Florentine education or at least consider him the "mastermind" behind some ideas and solutions: various elements of the building, such as the façade, the shape of the windows or the atrium to the east in fact recall his style

Others instead think of a direct pupil of Alberti, Francesco Cereo or del Cera (circa 1415-1468), called Francesco del Borgo because he was originally from Borgo San Sepolcro, near Arezzo. Remembered for the first time in Rome in 1450, Francesco is mentioned in the documents as architectus of the palace, employed by Paul II from November 1465 until his death in June 1468.

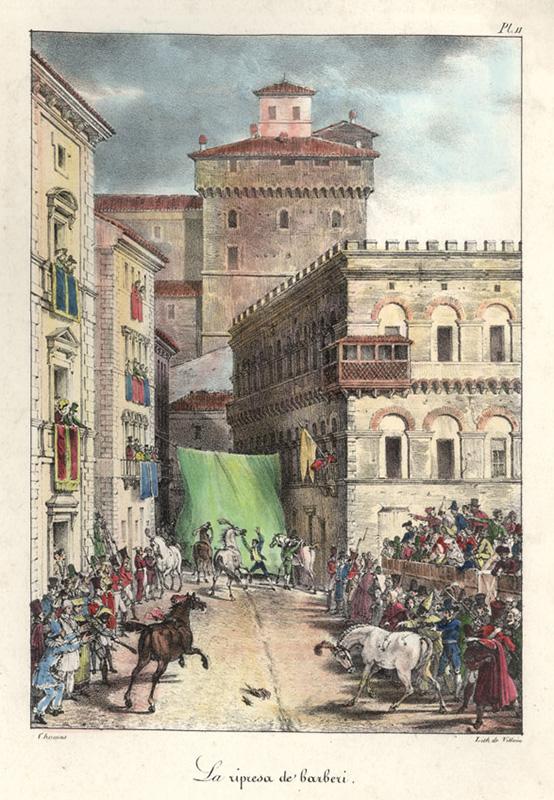

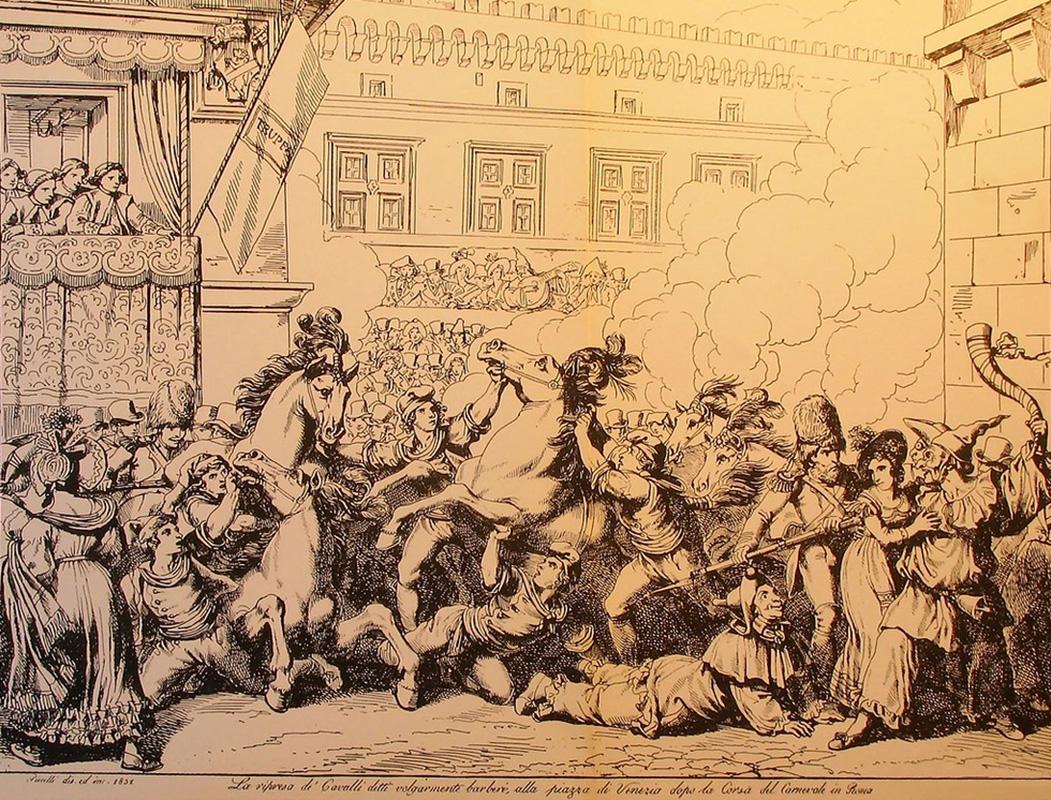

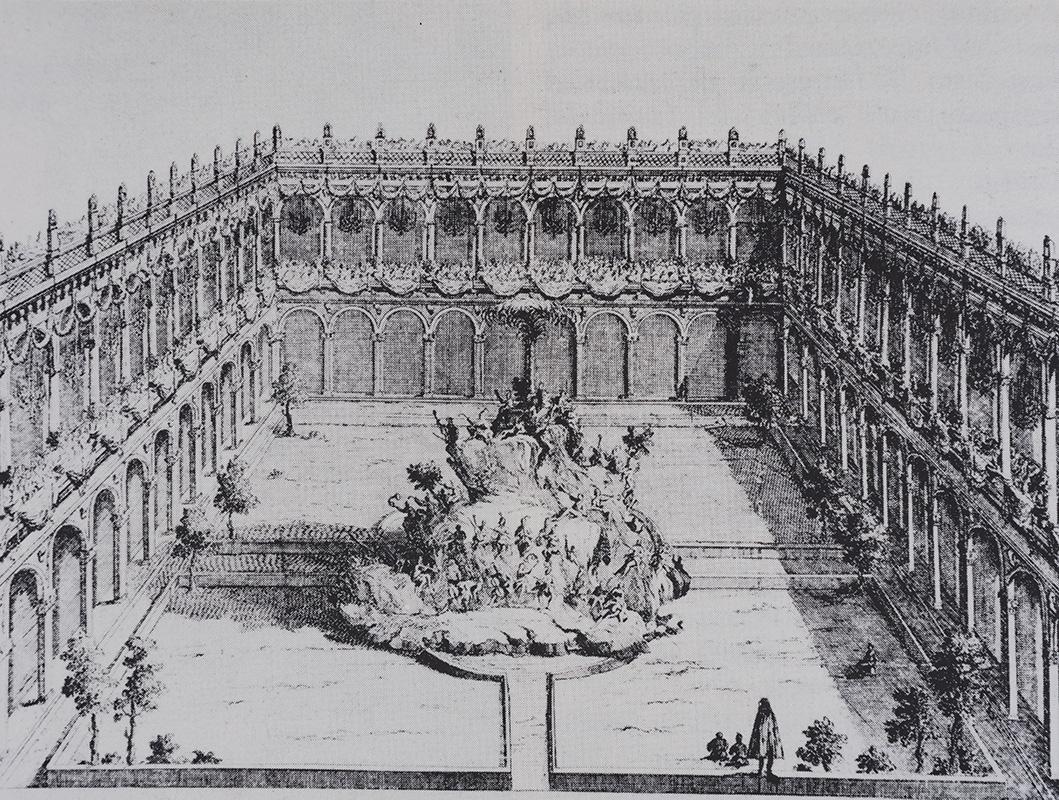

The fundamental layout of the complex, consisting of the palace, viridarium and church, dates back to that time. The viridarium or secret garden also served as a loggia. From the loggia you could enjoy a privileged view of the Carnival shows, which in 1466 Paul II transferred from Monte Testaccio. During the Carnival festivities, the pope used to invite magistrates and citizens to a solemn banquet, set up in the two internal arcades.

The palace was used to house Paul II's collection of art and antiquities, mostly consisting of coins, gems, precious stone carvings and semiprecious stone vases. Among the most important pieces, a sardonyx plate from the Hellenistic period stands out. This, formerly owned by Frederick II and known as the Farnese Cup, is now in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. According to the humanist Bartolomeo Sacchi (1421-1481), known as Platina, Paul II spent several of his nights admiring his treasures in the light of candelabra. The glare that filtered out through the windowpanes led to the popular belief that the building was inhabited by devils.

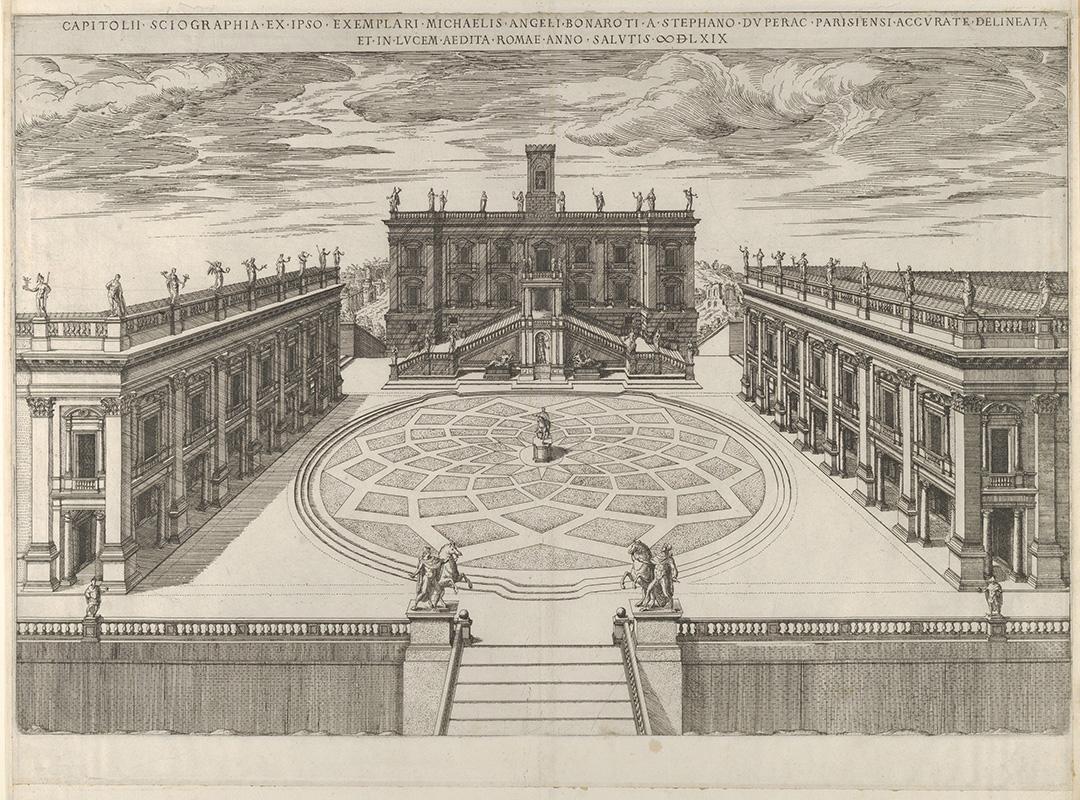

In an atmosphere of general recovery of the antiquarian heritage, Paul II began to transfer important classical artefacts to the immediate vicinity of the building. The goal was of course to increase its dignity, especially being in the presence of the Capitol, which had been the seat of the city magistrates since the Middle Ages and which embodied the residual ambitions of municipal autonomy.

The transfer of a large grey granite basin found in the Baths of Caracalla which was in the church of San Giacomo al Colosseo dates back to 1466. The basin, which for some time gave the square the name of “piazza della conca di San Marco (Saint Mark’s basin)”, would find its definitive location in piazza Farnese.

In 1467, Paul II had the Sarcophagus of Constance placed in front of the main façade of the building, facing east. This was made of red porphyry in the fourth century, probably in Alexandria in Egypt and had been located in the Roman church of Sant' Agnese until then. The new location lasted only a few years: at the death of Paul II, his successor Sixtus IV (1471-1484) returned the sarcophagus to the church. Its definitive transfer to the Vatican Museums dates back to 1788.

Paul II also toyed with the idea of moving here the equestrian monument of Marcus Aurelius, which at the time was located on the Lateran. For this reason, he had it restored by the Mantuan Cristoforo di Geremia (1410-1476), an expert in the field of medals and bronze art. In this case, however, the pontiff's plans did not take effect. Marcus Aurelius remained in its place: only in the sixteenth century would it find its final location at the top of the Capitol, within the framework of Michelangelo's layout.