Towards late Renaissance

Construction work continues with Cardinal Marco Barbo: the palace becomes one of the wonders of Rome, visited by tourists and diplomats, artists and writers

At the death of Paul II, in 1471, the great building site was still far from being completed. The task of continuing the work fell to his family member, Cardinal Marco Barbo (1420-1491), who had already taken over as titular of the Basilica of San Marco four years earlier. The coats of arms of Barbo junior, who resided in the trapezoidal apartment located inside the viridarium, can still be admired today in many areas of the building.

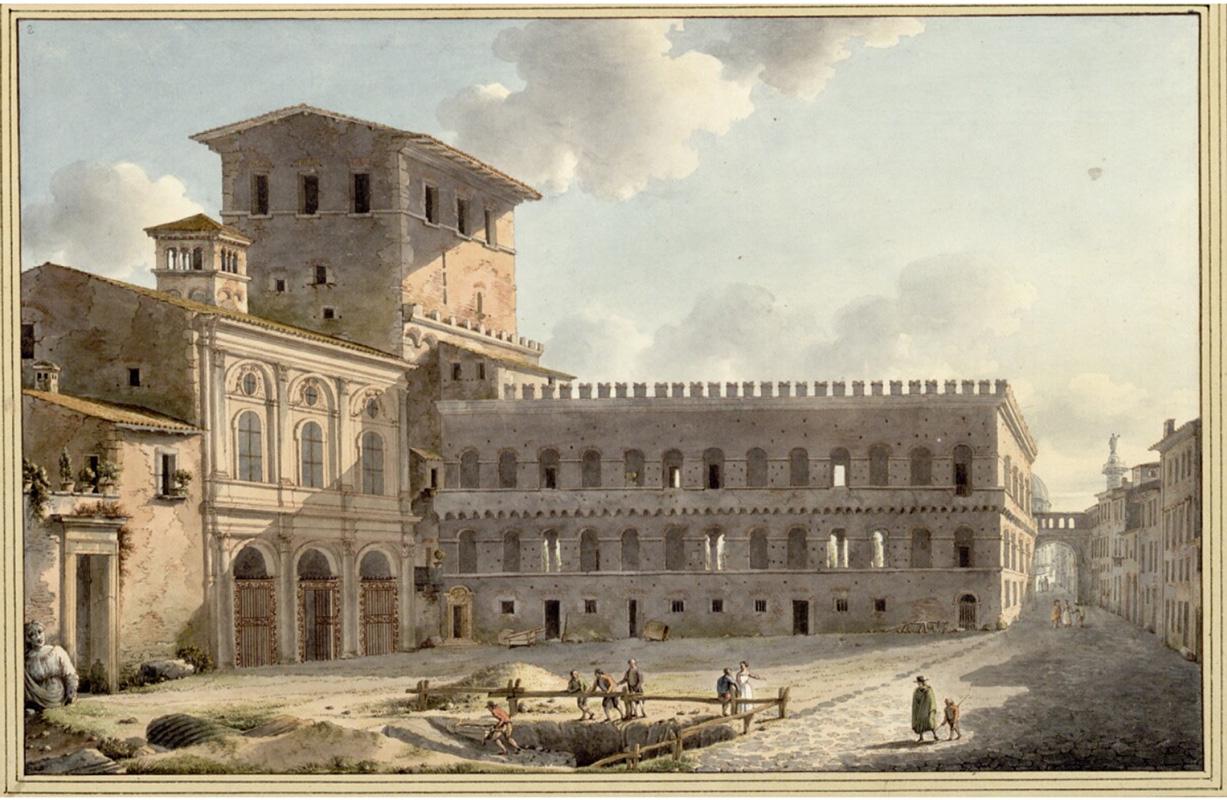

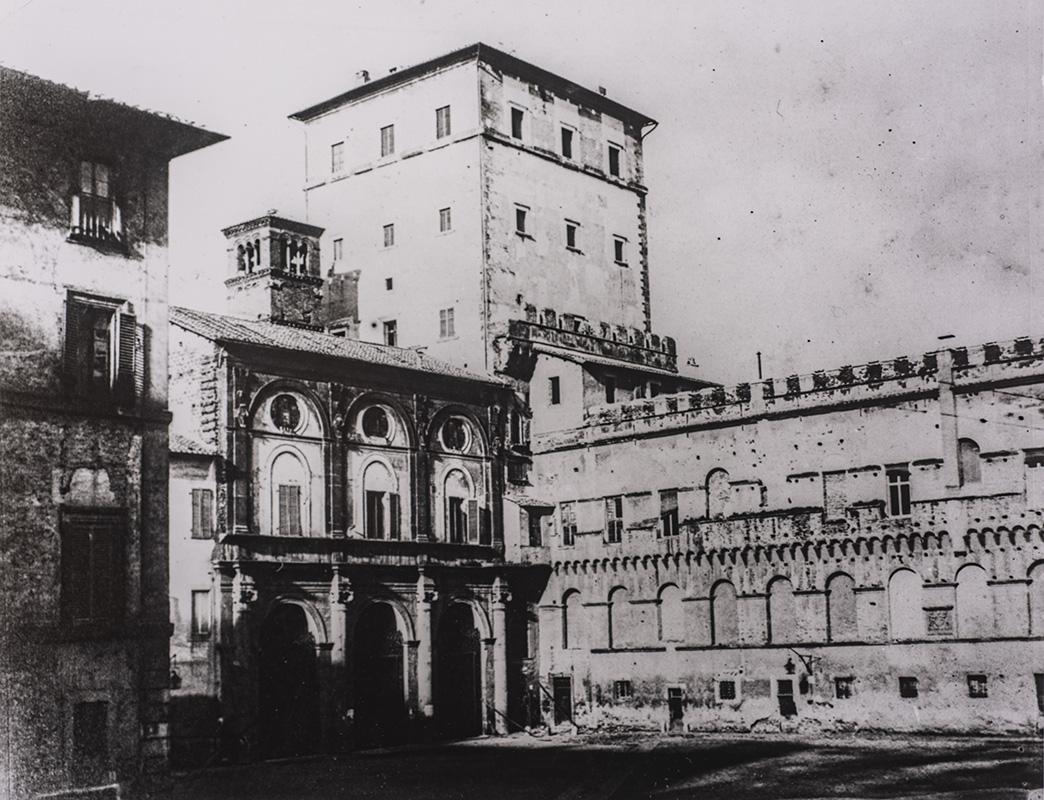

Recent studies show that many works completed can be attributed to him, including the second tier of the facade of Church of Saint Mark with the Benediction Loggia, the tower above the sacristy or roof terrace, the creation of the eastern edge of the complex with the construction of a crenellated corridor along Via degli Astalli, the portico of the courtyard and some frescoes, including the frieze with the Labours of Hercules.

The death of Cardinal Marco ended the Barbo era in the palace. The baton passed on to Lorenzo Cybo de Mari (c. 1450-1503). Lorenzo was born from the extramarital affair that the Genoese nobleman Domenico Mari had with a Spanish woman: the second surname was given to him by Giovanni Battista Cybo who, once he became pope as Innocent VIII (1484-1498), favoured his ecclesiastical career, among other things, by appointing him as the titular of the Basilica of San Marco in March 1491.

Once he had moved to the palace, Cardinal Lorenzo had the Sala del Mappamondo completed and had built the apartment along Via del Plebiscito, which still bears his name. The cardinal was also responsible for the placement of Madama Lucrezia, a colossal bust of the classical era from the Iseum Campense. Madama Lucrezia, together with Pasquino, was one of the famous 'talking statues' of Rome: even today it is possible to admire it to the left of the southern entrance of the building, in the square of San Marco.

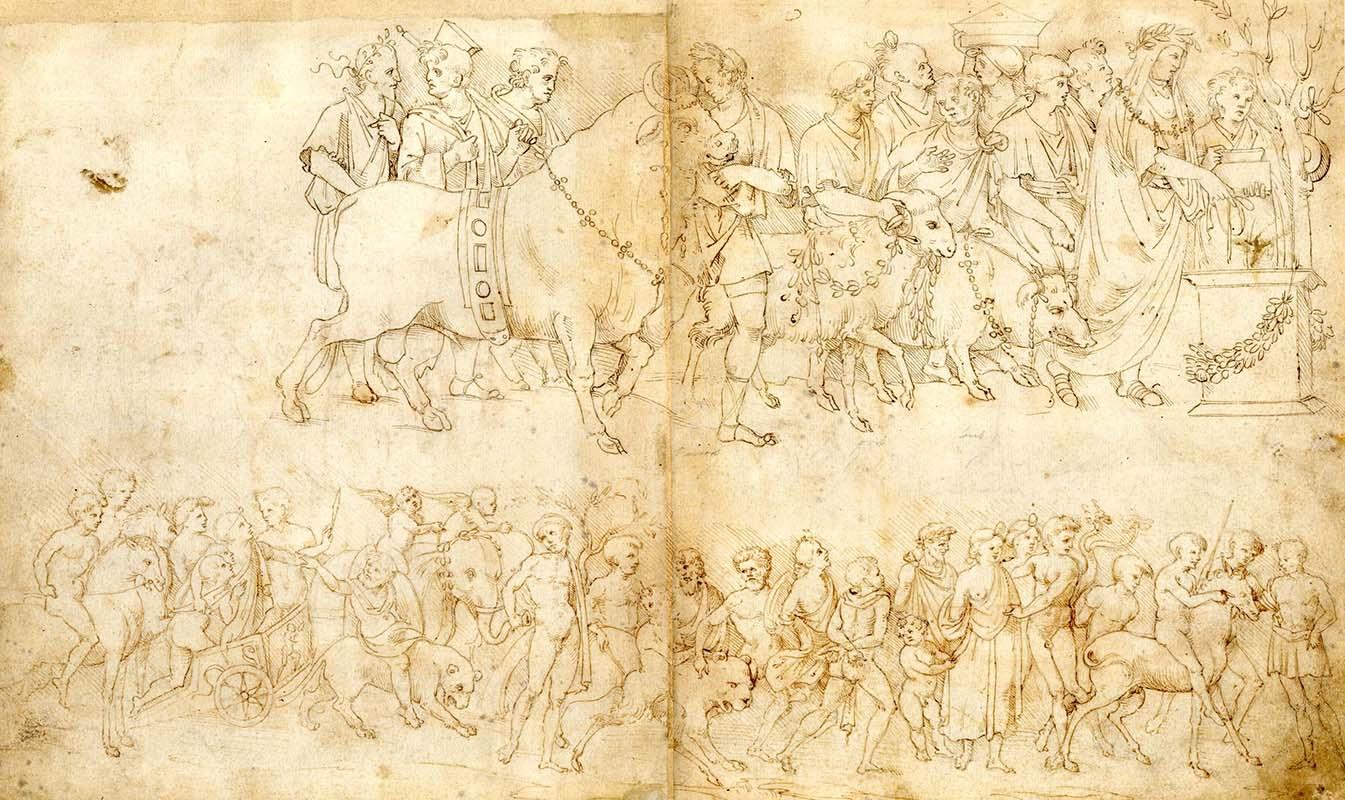

By the end of the fifteenth century the palace had already become one of the most beautiful and important buildings in Rome, capable of attracting travellers, writers and artists. The presence of the Bolognese painter Amico Aspertini (1474-1552), on a training trip to the city, was placed between 1496 and 1498 during the time of Cardinal Mari Cybo. The artist had an extraordinary passion for classical reliefs, which he used to copy on drawings. On this occasion he was attracted by a bas-relief depicting an ancient sacrifice, which was then inside the viridarium: his drawing, now preserved in the British Museum in London, bears the writing “in lo g[i]ardino de sancto marco (in San Marco’s garden)”.

The eldest son of the future doge Antonio Grimani (1434-1523), Domenico (1461-1524) embarked on a brilliant ecclesiastical career, which culminated in his appointment as cardinal, obtained at the hand of Pope Alexander VI Borgia (1492-1503) in exchange for the truly remarkable sum of 30,000 ducats. A graduate of the University of Padua and with an excellent cultural background, Grimani was one of the most eminent literati of his time. His entrance to the palace dates back to 1503, together with the appointment as titular cardinal of the Basilica of San Marco. The next twenty years corresponded to a further leap forward of the building in the field of literature and the arts.

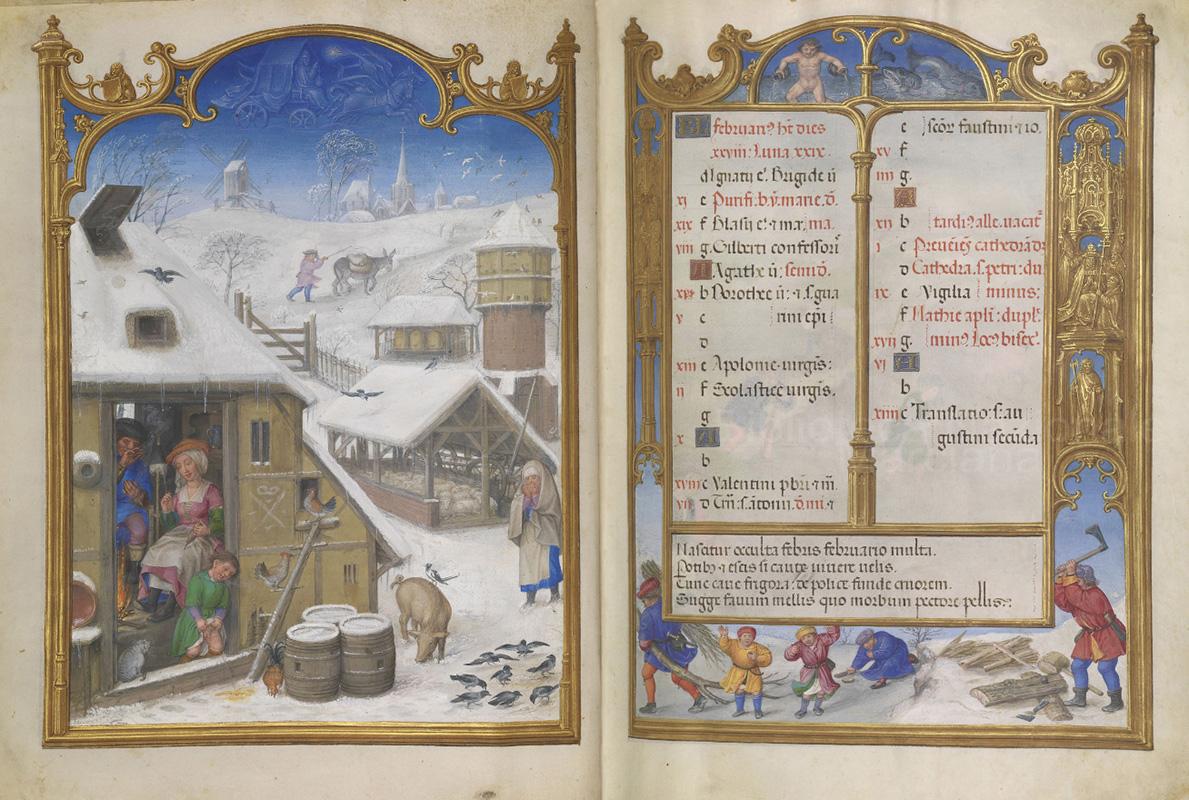

Cardinal Domenico Grimani also distinguished himself as a collector of books, art objects and antiques. The library, which already had several thousand volumes, was enriched in 1498 by the 15,000 bought from the heirs of the humanist Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494). His collection also included paintings of extraordinary value, attributed to artists such as Hieronymus Bosch, Giorgione and Raphael.

As the sources recall, including Francesco Albertini, a large part of the collection was housed in the Roman palace of San Marco, later migrating by will to his beloved Republic of Venice. This possibly occurred with the so-called Grimani Breviary, a Flemish illuminated manuscript from the second decade of the sixteenth century, now in the Marciana Library. As for the precious collection of classical finds, it would later become the founding core of the National Archaeological Museum of Venice.

Grimani's personality and his spectacular collection contributed to give prestige to the palace, which continued to capture the interest of the main visitors to the city. On 5th May 1505 - we read in the Diaries of the Venetian historian Marin Sanudo - the cardinal welcomed here the ambassadors of the Serenissima. As they walked through the various rooms, the guests were amazed by the study adjacent to his bedroom which was filled with books and classical sculptures: several had come to light during the excavation work that the prelate had carried out to build his villa on the slopes of Monte Cavallo, later incorporated into the perimeter of the current Quirinale gardens and palace.

Four years later it was the turn of Erasmus from Rotterdam (1466/69-1536). The Dutch humanist was at the end of his stay in the Peninsula, which began in 1506 and had been spent mostly in Turin, Bologna and Venice. One of the reasons that had guided him to Italy was the desire to improve his knowledge of classical languages and to buy books and manuscripts. Arriving in Rome in early 1509, Erasmus went to visit the palace of San Marco, perhaps in the company of Pietro Bembo (1470-1547): he was able to admire the collection and above all the library of Cardinal Grimani, about which he would later compose words of admiration.