At last the Kingdom of Italy

During the First World War, the palace passed to the Kingdom of Italy. A new chapter then opens, in the name of the museum

On 24th May 1915, Italy entered the First World War, siding alongside England and France against Germany and Austria. Although several hundred kilometres away from the front, in its own fashion, Palazzo Venezia also became a place of contention. Until then, the Empire had maintained two distinct embassies in Rome. The one in Palazzo Chigi, previously rented by the self-same princes, was used by the Kingdom of Italy and had been closed the day after the declaration of war. The second in Palazzo Venezia housed the embassy to the Holy See and, precisely as such, continued to remain in operation for another eighteen months.

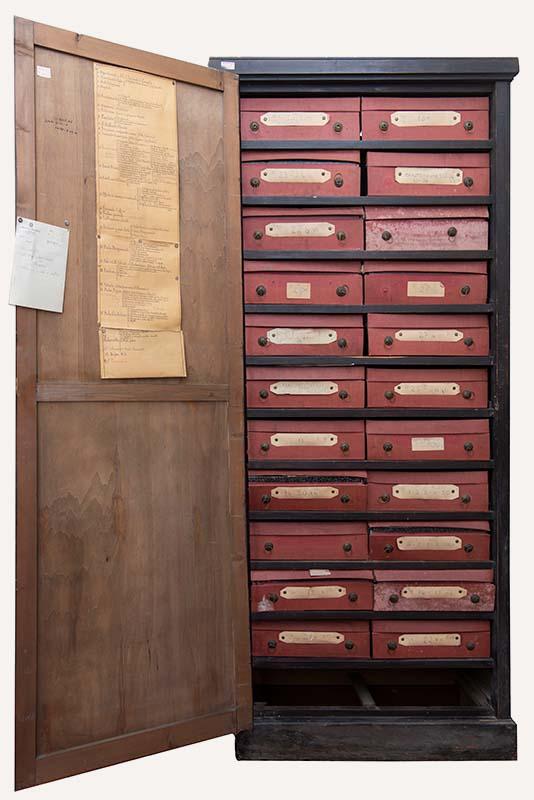

In August 1916, with mounting frustration for the outcome of the conflict and anger at the Austrian bombing of the Serenissima, the Italian government decided to requisition the building from the enemy. The handover took place on 1st November of the same year. It was a mere bureaucratic act: at 14.00 pm sharp, as agreed, the Minister of Finance Filippo Meda, accompanied by a notary and two officials, knocked on the door of the building, to collect "the keys without opposition".

The expropriation of Palazzo Venezia also became a diplomatic issue, not so much with the Austrian enemy, but with the Vatican, which naturally claimed the rights to this embassy. In order to soften the tone of the controversy, as early as 15th October, that is even before the handover, the Italian government published a decree that designated the building as a museum.

The official name, Museum of the Palazzo di Venezia, is due to art historian Corrado Ricci (1858-1934), at the time head of the Antiquities and Fine Arts General Directorate. Ricci had great confidence in the future of the new institute: "What must triumph for us - he wrote to the Minister of Education Francesco Ruffini - is the name of Palazzo Venezia and the public will need to say, “Let's go to the Palazzo di Venezia” just as it says 'Let's go to the Louvre...'".

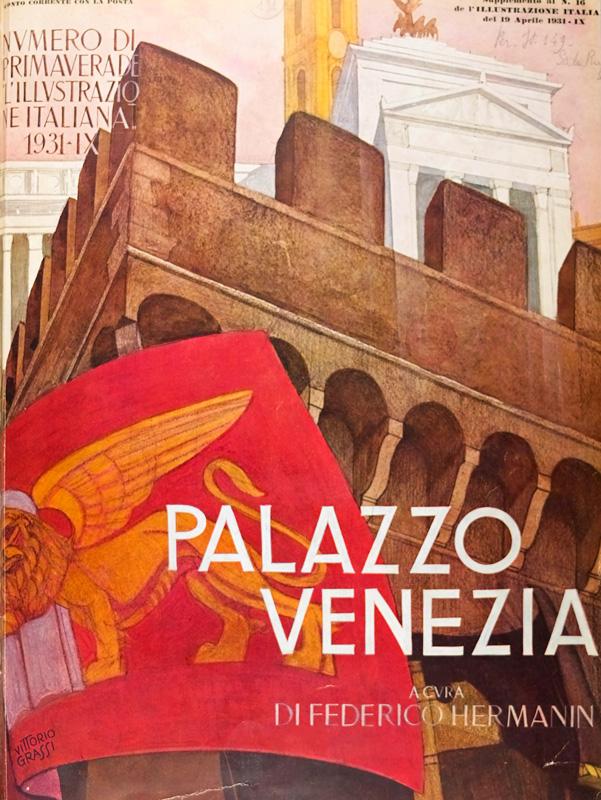

Housed in Palazzo Venezia, unanimously considered one of the clearest and most majestic expressions of the Italian Renaissance, the museum was born with great expectations. In line with its container, the idea arose of making it the Museum of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The position of first director fell to art historian Federico Hermanin (1868-1953), as superintendent of the Galleries and Museums of Lazio and the Abruzzi.

Already the following year, 1917, Hermanin, assisted by Corrado Ricci, was able to develop an exhibition project, according to which the museum should take on the features of a noble residence of the sixteenth century.

At that stage, the conditions of the building appeared to be critical. Over the centuries, several rooms had undergone profound tampering, which had compromised their original structures and spatiality. Just think that the Sala del Mappamondo and the Sala Regia, in addition to having been fragmented into various rooms, were simply devoid of ceilings and floors. Hermanin did a remarkable job. After demolishing the partitions, the director conducted the first research on the ancient walls: fragments of frescoes from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries emerged, which he attributed respectively to Mantegna and Bramante.

At the same time, works were selected from the deposits and exhibition rooms of the other Capitoline museums, to be sent to Palazzo Venezia. As well as towards Castel Sant'Angelo, Hermanin turned his gaze towards the National Gallery of Ancient Art, at the time located in Palazzo Corsini: his attention fell on the pieces coming from the Monte di Pietà and on those left by Henrietta Hertz (1846-1913) at her death in 1913.

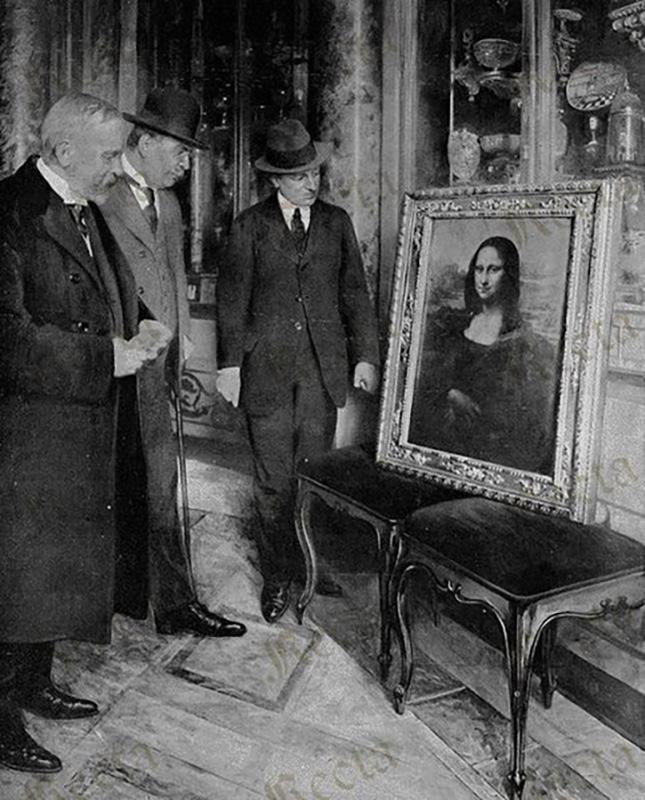

The museum project therefore took shape, albeit amid growing difficulties. The main one is to be found in the setbacks suffered by the Italian army in the summer-autumn of 1917. In the weeks following the defeat of Caporetto, which took place on 24th October, the building took on the role of an emergency shelter for works of art arriving from the cities that were most vulnerable to the Austrian troops, starting with Venice. Hence the temporary presence in the palace of masterpieces transferred in haste from the Serenissima, such as the bronze quadriga of San Marco and the equestrian Monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni by Verrocchio, documented by period photographs.

The situation took a decisive turn in the autumn of 1918 with the triumph of Vittorio Veneto and the subsequent surrender of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In this new and different dimension, Palazzo Venezia, taken away from Vienna, became one of the symbols of the victorious tricolour. The museum inside travelled on the wings of this patriotic enthusiasm. In 1919, director Federico Hermanin offered a preview, setting up a selection of the works which had converged into the collections in some rooms of the Cybo Apartment. The goal was to persuade citizens that "the glorious Palace is intended to house a museum of painting, sculpture and minor arts".

In June 1921, the support of Benedetto Croce (1866-1952), then Minister of Education, allowed opening the first rooms of the museum, located inside the Barbo Apartment. However, that set-up was short-lived. After just one year, Hermanin was forced to vacate the Barbo rooms to make way for the exhibition of the works that Austria had had to return to Italy. The exhibition, marked by the tones of an increasingly accentuated nationalism, opened its doors in December 1922: with an installation designed by Armando Brasini (1879-1965), one of the enthusiastic spectators was Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), who a few weeks earlier, had taken over the reins of the government.