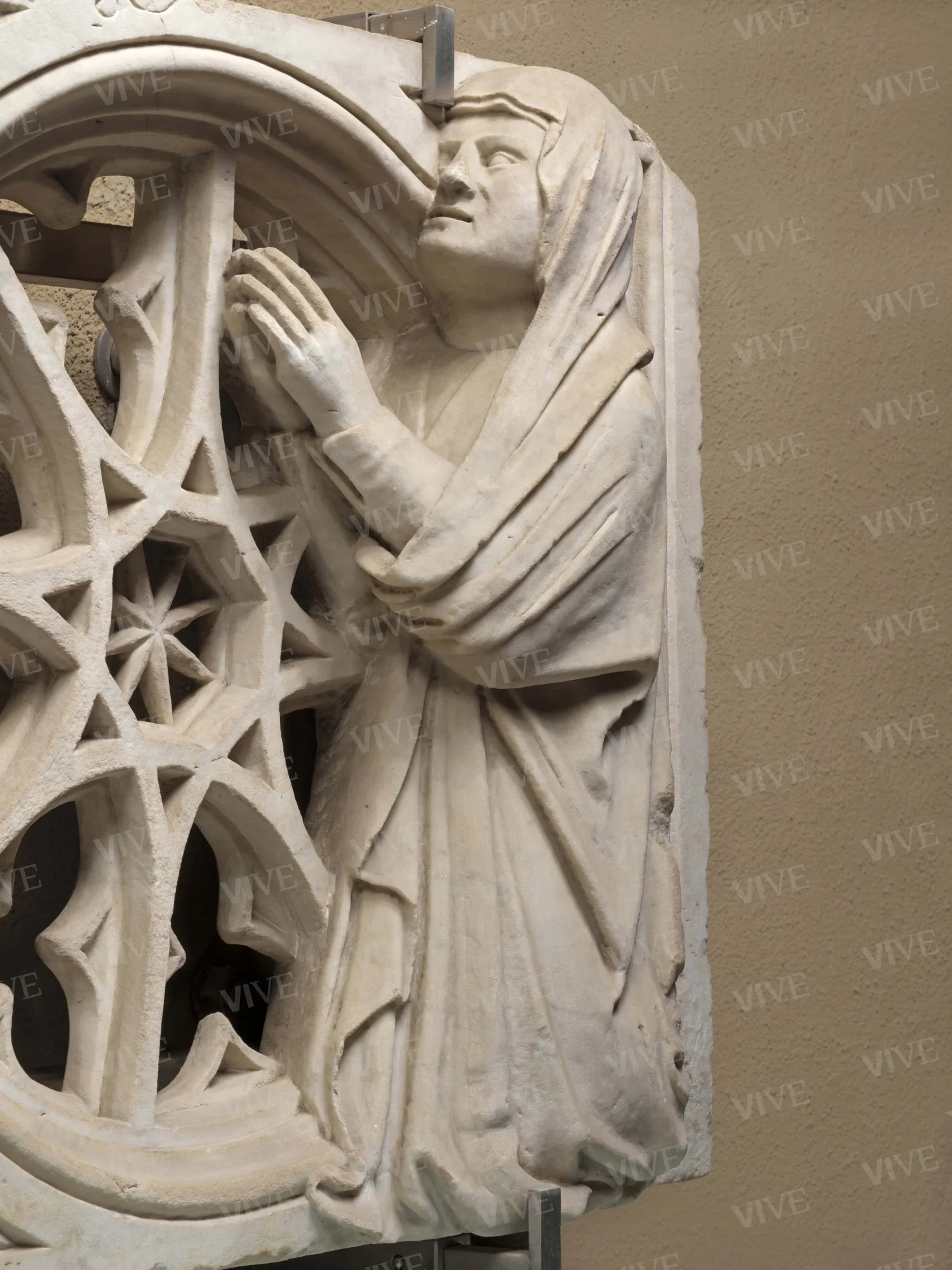

Transenna with two donors

Giovanni di Stefano da Siena 1372

The transenna was the front of the ciborium containing the icon of the Virgin Mary at the Aracoeli. Disassembled around the second half of the sixteenth century, its has been reconstructed thanks to surviving fragments and documentary records. The transenna played a prominent role in this restitution because of the two patrons (Francesco and Catherina Felici), the inscription that also bears the year 1372, and its state of conservation, which made it possible to identify the figurative artistic context to Giovanni di Stefano, a Sienese architect and sculptor who was active in Rome from 1368.

The transenna was the front of the ciborium containing the icon of the Virgin Mary at the Aracoeli. Disassembled around the second half of the sixteenth century, its has been reconstructed thanks to surviving fragments and documentary records. The transenna played a prominent role in this restitution because of the two patrons (Francesco and Catherina Felici), the inscription that also bears the year 1372, and its state of conservation, which made it possible to identify the figurative artistic context to Giovanni di Stefano, a Sienese architect and sculptor who was active in Rome from 1368.

Details of work

Catalog entry

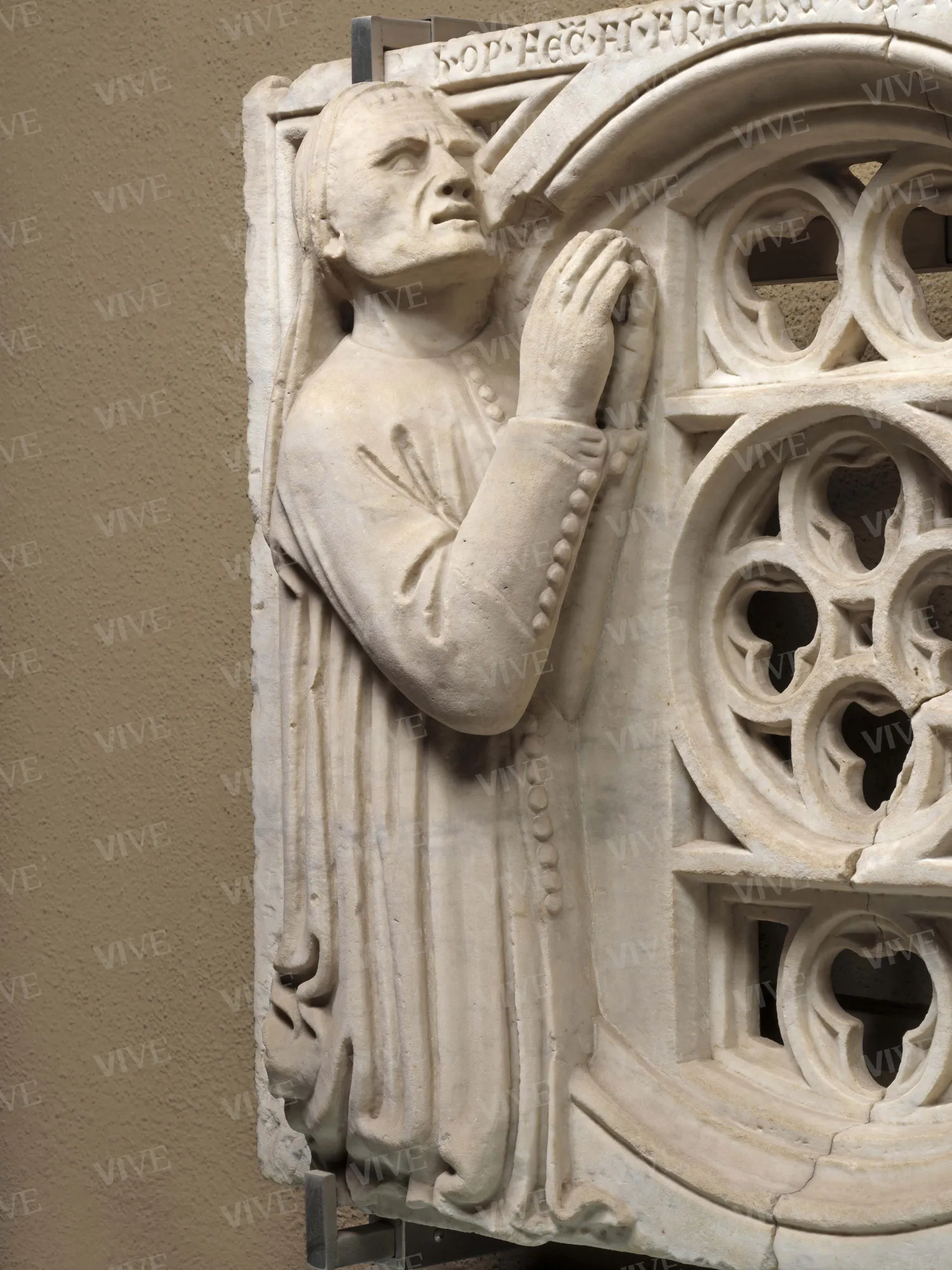

This marble transenna with donors was the front of the ciborium containing the icon of the Virgin Mary at the Ara Coeli. Unfortunately disassembled around the second half of the sixteenth century, it has been reconstructed (Bolgia 2005; Bolgia 2017, 348–388) on the basis of surviving fragments and direct and indirect documentary reports. The transenna played a prominent role in this restitution as it was characterized by the presence of the two patrons, who are identified thanks to the name of the notary Francesco Felici and the year 1372 in the inscription. The other donor has been identified deductively as Catherina Felici, Francesco's wife, according to numerous assertions in the scholarly literature.

The transenna has also been essential in identifying the figurative milieu in which the now lost ciborium was produced. Production has been traced back to the milieu of Giovanni di Stefano (Santangelo 1954; Tomei 1979; Bolgia 2005; D'Alberto 2013; Bolgia 2017), a Sienese architect and sculptor who in 1366 worked at the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena and was already active in Rome in 1368, most likely on the site of Saint John Lateran, where Pope Urban V engaged him to create the ciborium of the Princes of the Apostles.

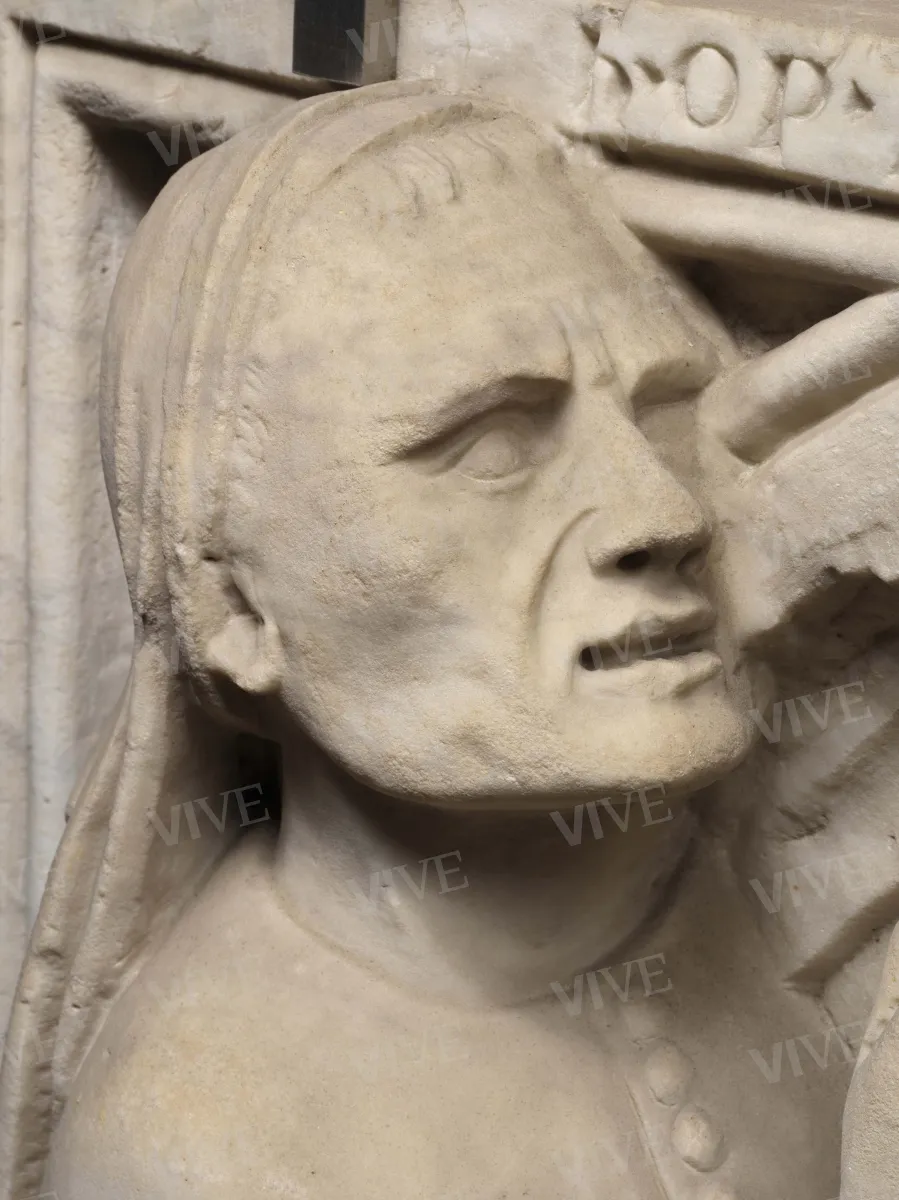

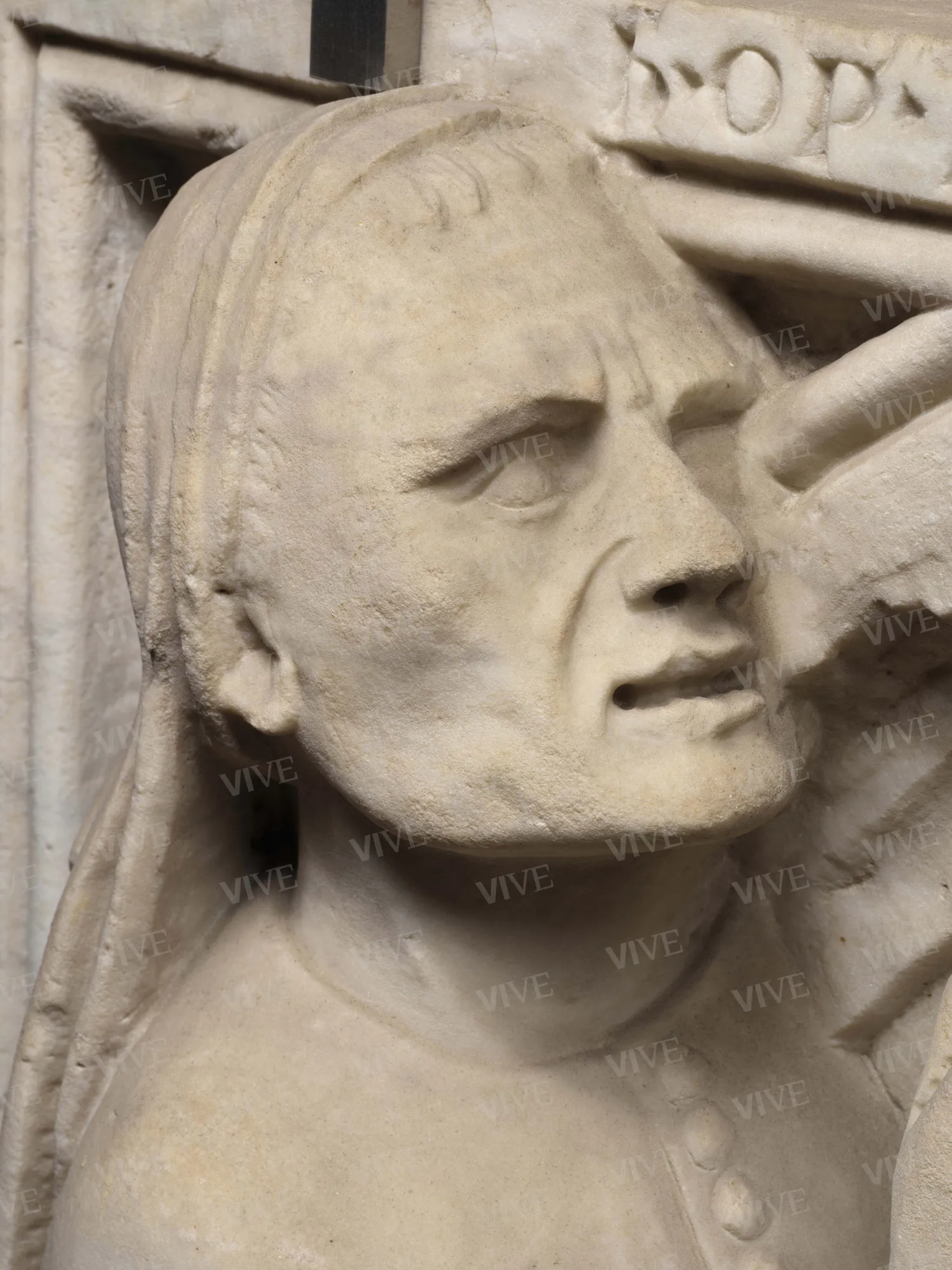

Giovanni di Stefano's figurative culture was greatly indebted to Giovanni Pisano, whom he had studied in Siena cathedral and from whom he inherited the decorative opulence of the draperies and the monumental, expanded volumes of the forms. The Roman works are also characterized by an early reflection on the signed works of Arnolfo di Cambio and at the same time enriched with a strong transalpine component that di Stefano assimilated by working in Rome’s papal building sites where French masters were present. Very quickly, di Stefano managed to monopolize the most important sculptural commissions in Rome. He was often called on, not only by the pontiffs and dignitaries of the papal curia but also by representatives of Rome’s upper middle class, including Francesco Felici. This was most likely because di Stefano had rapidly succeeded in organizing an industrious workshop whose stylistic mark was not simply rooted in the past, but that experimented with new "pre-humanistic" sensibilities foreshadowing the arrival of Giovanni d'Ambrogio, Lorenzo di Giovanni, and Piero di Giovanni Tedesco in Rome in the 1390s. The Felici piece clearly evinces all these components.

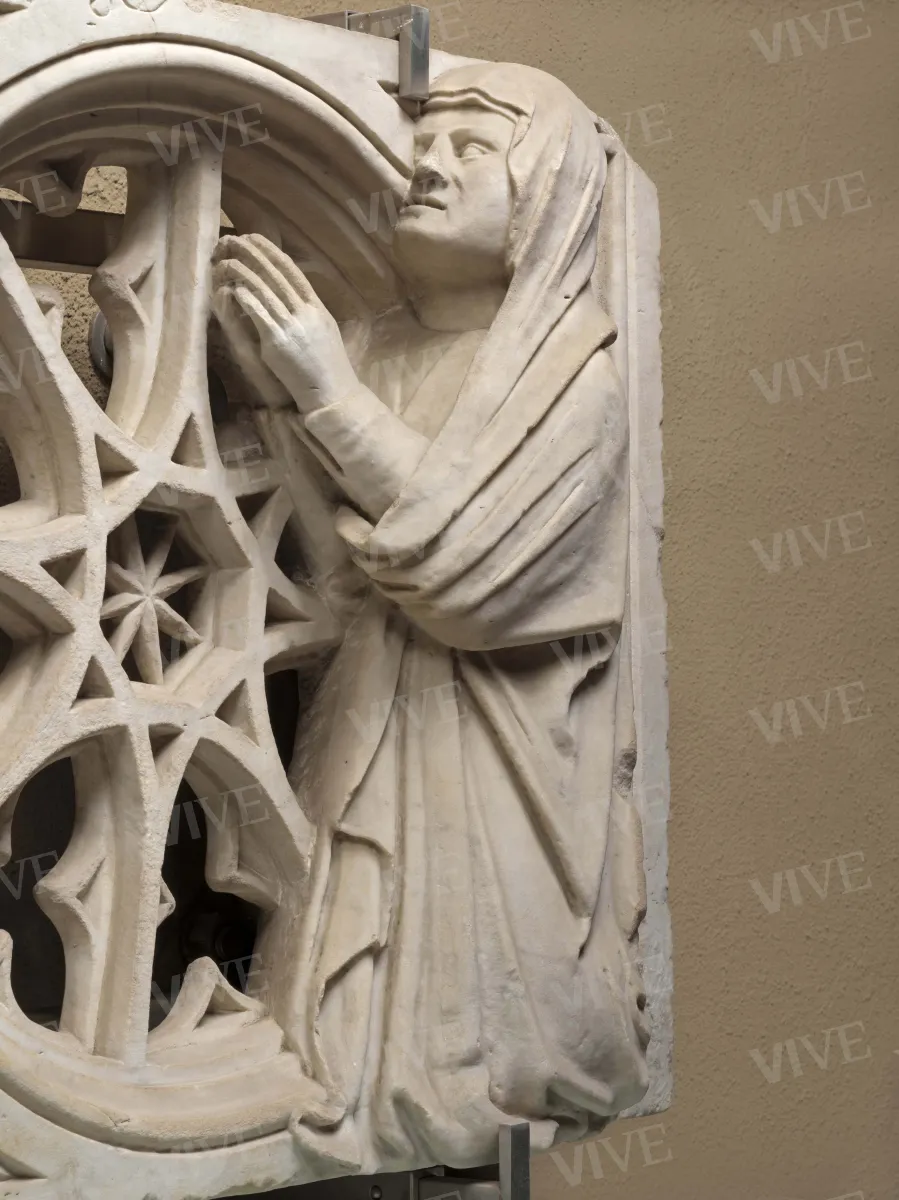

The stonework is in fact the result of a reflection on Giovanni Pisano. The study of the illustrious Pisano enabled di Stefano to create the drapery through deep tubular grooves and wide "V" folds that manage to dialogue with the bodies below and the pose of the two praying figures. The depth of the grooves applied to the drapery is, moreover, commensurate with the slab’s intended prominence. The transenna, in fact, was positioned rather high and surmounted the front columns of the canopy and constituted the base of the tribune designed to accommodate the Ara Coeli icon of the Virgin Mary. The creation of two planes—where the first accommodates the praying figures, who are sculpted in the half-round, and the second is characterized by a geometric fretwork contextualizing the two figures—is a compositional form that can be found in French Gothic retables from as early as the thirteenth century (see in particular the Saint-Denis Crucifixion retable in Paris). The transalpine modernization of di Stefano's stylistic language can also be seen in the tracery of the transenna where the three rosettes are given three distinctly different designs, but where the entire piece is based on the trefoil motif. The left rosette, towards which Francesco Felici is leaning, is divided into nine fields, each filled with pairs of round-arched trilobed clypei. However, the trefoil pointed-arch is dominant in this rosette, and it is repeated eight times framed by ogival arches to form an eight-pointed star. The central rosette, which is unfortunately cracked in the middle, is made up of eight intersecting circles forming a flower whose petals surround a trefoil motif that expresses in microarchitectural terms a series of single-light pointed arches.

Because of its decorative style, the Ara Coeli transenna has rightly been compared to two very similar transennae along the north wall of the cloister of the former monastery of Santi Bonificaio e Alessio on the Aventine. The similarities between the marble pieces are so striking that for many years it was believed that the Aventine transennae also came from the lost ciborium of the Ara Coeli (Santangelo 1954). Thanks to a groundbreaking study by Manuela Gianandrea (2009), it was established that these were part of another ciborium, unfortunately also lost, erected in the church of Santi Bonificaio e Alessio and used for the conservation and display of the icon of the Virgin Mary held by the church and exemplified on the prototype of the Ara Coeli.

Finally, the refined Gothicism outlined so far combines with a pre-humanistic experimentalism found particularly in the portrait characterizations of the faces of the two praying figures and the rendering of their robes based on the latest fourteenth-century fashion.

Claudia D'Alberto

Entry published on 12 February 2025

State of conservation

Fair. The middle section of the central rosette is split. In a stock photograph published by Bolgia (2005) and erroneously described as "from Santangelo 1954," the central rosette is reconstructed with a plaster reproduction section. Bolgia states that this addition was removed at some point between 1954 and 2000. In fact, the transenna already appears to be devoid of much of its marble lattice-work in Santangelo 1954. In an inventory card, undated but later than the OA card compiled by Alessandro Tomei in 1979, it is first noted that "most of the central rosette is missing."

Restorations and analyses

Restorations 1984; 2000; 2002–2003.

Inscriptions

«H(oc) OP(us) FEC(it) FI(eri) FRANCISC(us)»;

«DE FELICIB(us) AD HONORE(m)»;

«GLORIOSE [...] MCCCLXXII».

Provenance

Rome, church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli;

Rome, Tabularium Capitolino, 1888;

Rome, Museo di Castel Sant’Angelo, 1911;

Rome, Museo di Palazzo Venezia, from 1920.

References

Santangelo Antonino, Museo di Palazzo Venezia. Catalogo delle Sculture, Roma 1954, pp. 11-12;

Bolgia Claudia, The Felici icon tabernacle (1372) at S. Maria in Aracoeli reconstructed: Lay patronage, sculpture, and Marian devotion in Trecento Rome, in «Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes», LXVIII (2005), pp. 27-72;

Gianandrea, in Barberini Maria Giulia, Tracce di Pietra. La collezione dei marmi di Palazzo Venezia, Roma 2008, pp. 222-224, n. 57;

Gianandrea Manuela, Le lastre gotiche nel chiostro dell’ex convento dei Santi Bonifacio e Alessio all’Aventino. Un’ipotesi per il perduto ciborio dell’immagine mariana e una riflessione sui cibori per icona nel tardo medioevo romano, in «Studi romani», LVII (2009), 1/4, pp. 164-181;

D’Alberto Claudia, Roma al tempo di Avignone. Sculture nel contesto, in «Saggi di Storia dell’Arte», Roma 2013, pp. 177-178;

Bolgia Claudia, Reclaiming the Roman capitol: Santa Maria in Aracoeli from the altar of Augustus to the Franciscans, c. 500-1450, London 2017.