Terracina Chest

Central–southern Italy Late-11th–first half of 12th century

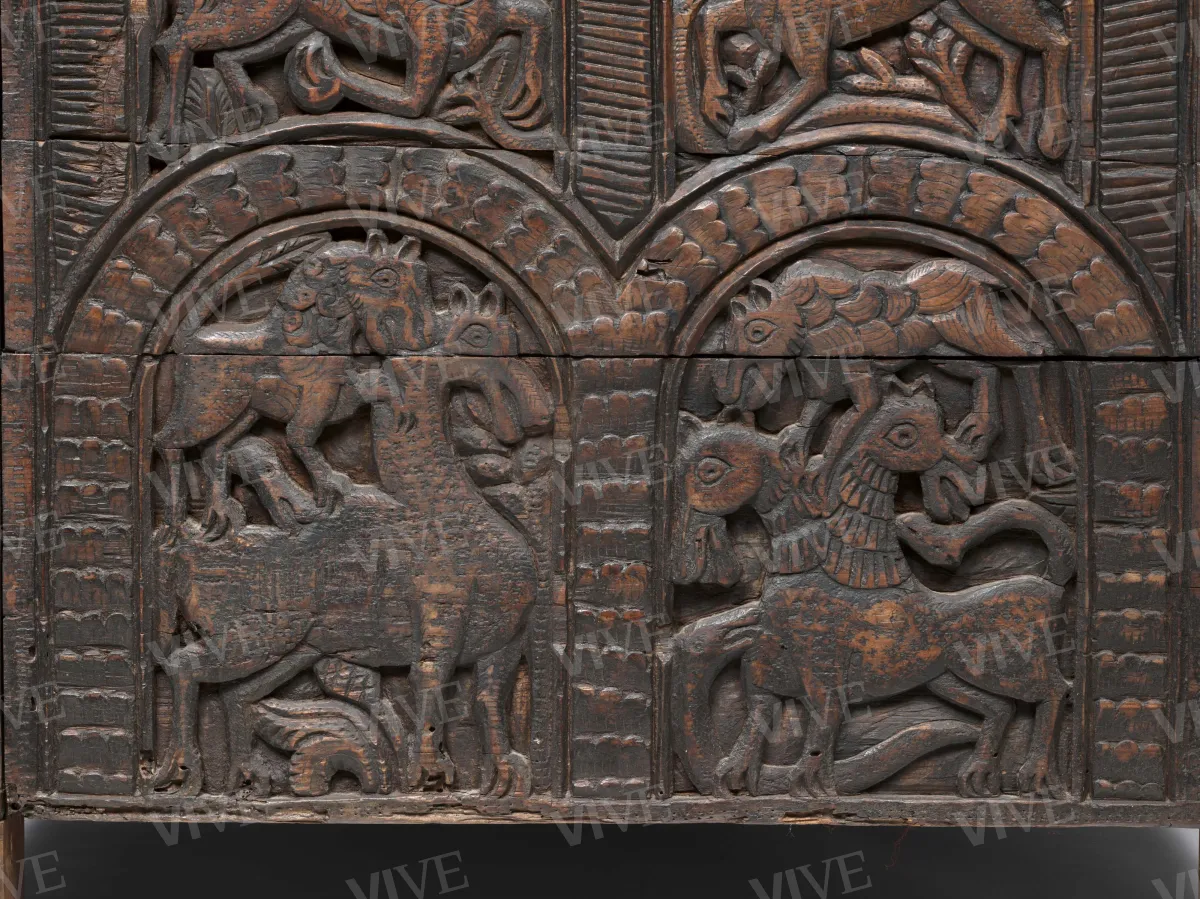

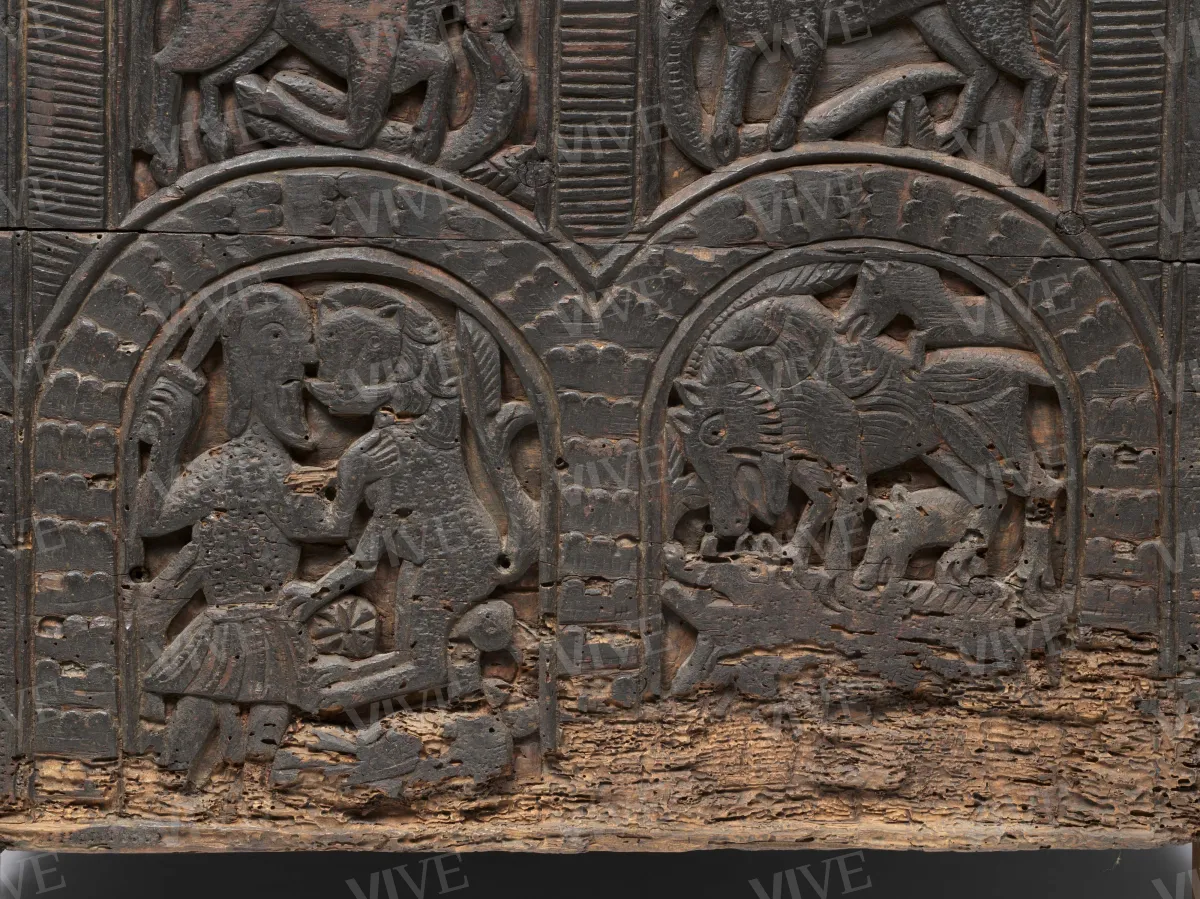

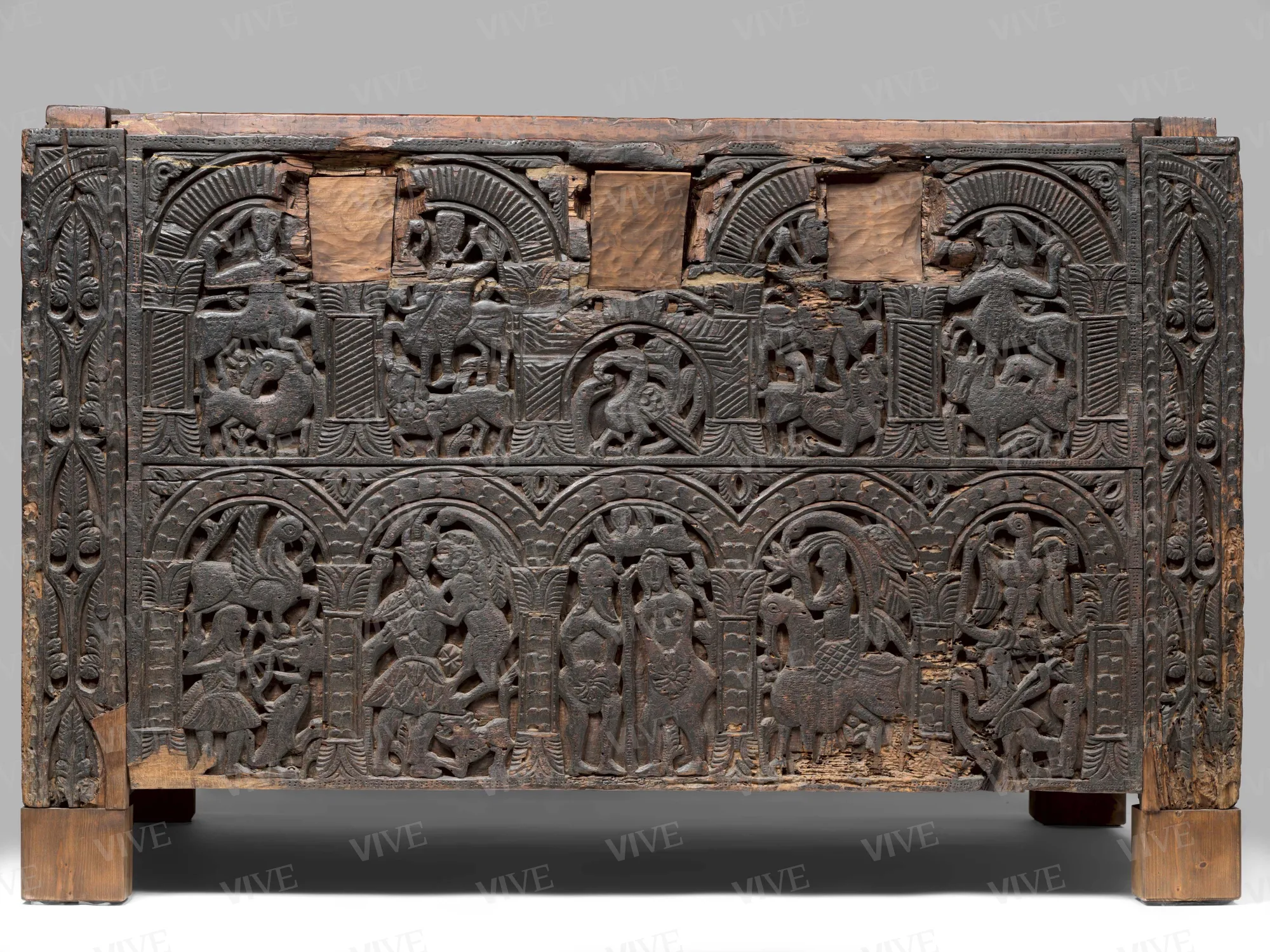

The parallelepiped-shaped chest is assembled by means of wooden recesses and pins. The outer surface is decorated in relief on three sides—the front and two sides—punctuated by two orders of overlapping arches that, in the lower central band, frame the Sin of the Progenitors, or the Original Sin, and then a series of conflicts between men and real or fantastical animals taken from the Bestiary tradition. A stylized palmette motif also runs along the uprights and was originally designed to continue down into the feet, which were removed and replaced by modern elements.

The parallelepiped-shaped chest is assembled by means of wooden recesses and pins. The outer surface is decorated in relief on three sides—the front and two sides—punctuated by two orders of overlapping arches that, in the lower central band, frame the Sin of the Progenitors, or the Original Sin, and then a series of conflicts between men and real or fantastical animals taken from the Bestiary tradition. A stylized palmette motif also runs along the uprights and was originally designed to continue down into the feet, which were removed and replaced by modern elements.

Details of work

Catalog entry

The chest is decorated in relief on three sides marked by a double series of arches. In the center of the front is the Sin of the Progenitors, or Original Sin, flanked by the serpent which recurs in the clypeus above as it is attacked by a peacock. The theme of the struggle between different creatures continues on to the side arches where, in the upper register, two horsemen impale ferocious beasts with their spears and are confronted by two sword-wielding centaurs trampling a lamb or a fawn and a bull. The only axial correspondence between these groups and those below is the lion in the lower band being pecked by a peacock or phoenix while fighting a warrior. To the right of Adam and Eve, on the other hand, a man riding a camel appears to be bending a branch to catch the phoenix or peacock again. Finally, at the extremes, a griffin surmounts an archer shooting an arrow at a boar or bear being attacked by a fox, while on the opposite side a man with a spear fights a snake being clawed at by an eagle with it wings spread. This also appears in the left panel juxtaposed with a fawn or lamb crushing a snake while, in the preceding arch, a griffin towers over a lion attacked by a small animal, which in the band below is attacking a camel along with a wild beast. In the following arch, a wolf and a snake attack a two-headed quadruped, possibly Orthrus. In the right panel, the first upper arch contains a centaur and a bull wrestling with a snake, against which, in the next arch, a deer topped by a peacock is struggling. Finally, the lower register contains a bearded warrior facing a lion with his sword and then a wolf assaulting a wild boar.

Identification of the individual subjects is in some cases hampered by the little more than sketchy morphological characteritics available and uncertainties in the depiction of exotic or fantastical animals, but the overall picture is entirely clear and allows us to read the bestiary on the chest in the context of the contrast between good and evil, declined according to themes glorifying hunting and animal combat. The choice to develop these themes by means of a tangle of vegetation and fighting figures harks back to artifacts of Islamic derivation, such as the ivories produced in southern Italy between the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Moreover, the surface treatment of the figures carved on the chest, which are covered in deeply incised signs in the shape of a cross, also recalls this production. However, this is not the only cultural intersection in this exceptional artifact. The taste for relief depictions of monstrous animals seems to find its roots in early medieval Campania sculpture and to have been updated through the circulation of cloth and metalwork from Byzantium. A place of convergence for such heterogeneous cultural stimuli was certainly the site of the abbey of Montecassino, where sources attest to the presence of works and artists from all over the Mediterranean basin and fine carved woodwork. The relationship between Terracina and Montecassino, moreover, was intense and long-lasting—it was perhaps as early as 1061 that the city was entrusted to Desiderius (later Pope Victor III), and the presence of bishops trained in the abbey lasted at least until the 1120s. During this period the cathedral complex was extensively restored, which involved the construction of a cloister and the renovation of the church, its decorative apparatus, and furnishings, which may have included the chest. If this were the case, then the chest would therefore date to between the end of the eleventh century and the first half of the twelfth.

It has been hypothesized that the chest was designed to contain books and documents. However, its horizontal layout, low height, and the reduced size of the inner compartment make it unsuitable for this function, and it also true that the decorative themes would lend themselves just as poorly. It should therefore be considered that it may have been an ark designed to contain relics such as the cypress relic, which Leo III had had made for the Sancta Sanctorum and was used as an altar in the late eleventh century. The storyline linking Terracina to Montecassino and Rome in the climate of the Gregorian Reformation, with the renewed centrality of the altar as a place of sacrifice and martyr worship and the focus on the bestiary as a metaphor for the eternal struggle between good and evil thus seems to provide the coordinates for the framing of the Terracina chest as well, which perhaps originally belonged to the altar–confessional block of the cathedral, which, despite transformations, maintained a layout similar to that of coeval Roman churches.

Gaetano Curzi

Entry published on 12 February 2025

State of conservation

Good; note, however, limited woodworm damage, removal of feet, three holes on front for insertion of locks, and missing lid.

Restorations and analyses

2010: restoration performed by Geremia Russo under the direction of Lucia Calzona.

Provenance

Found in 1888 in a compartment above the sacristy of the cathedral of Terracina;

sold to the Italian state by the cathedral chapter in 1909.

Exhibition history

Rome, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo Venezia, La cassa di Terracina: piccole e grandi storie di un mobile tra Oriente e Occidente, May 12–June 14, 1987;

Terracina, Museo Civico, La cassa di Terracina: piccole e grandi storie di un mobile tra Oriente e Occidente, July 15–September 15, 1987.

Sources and documents

Documentation on the purchase of the chest is kept at the Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Terracina, and the Archivio Comunale, Terracina.

References

Rech Clara (a cura di), La cassa di Terracina: piccole e grandi storie di un mobile tra Oriente e Occidente, catalogo della mostra (Roma, Museo Nazionale del Palazzo Venezia, 12 maggio-14 giugno 1987; Terracina, Museo Civico, 15 luglio-15 settembre 1987), Roma 1987;

Grossi Venceslao, La vicenda amministrativa della “cassa” di Terracina, in Antichità e belle arti a Terracina: la gestione dei beni culturali fra il 1870 e il 1915 nei documenti dell'Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Terracina 1994, pp. 203-258;

Curzi Gaetano, La cassa lignea di Terracina tra Riforma e crociata, in Nuzzo Mariella, Gigliozzi Maria Terera (a cura di), Terracina nel medioevo. La cattedrale e la città, Roma 2020, pp. 115-112.