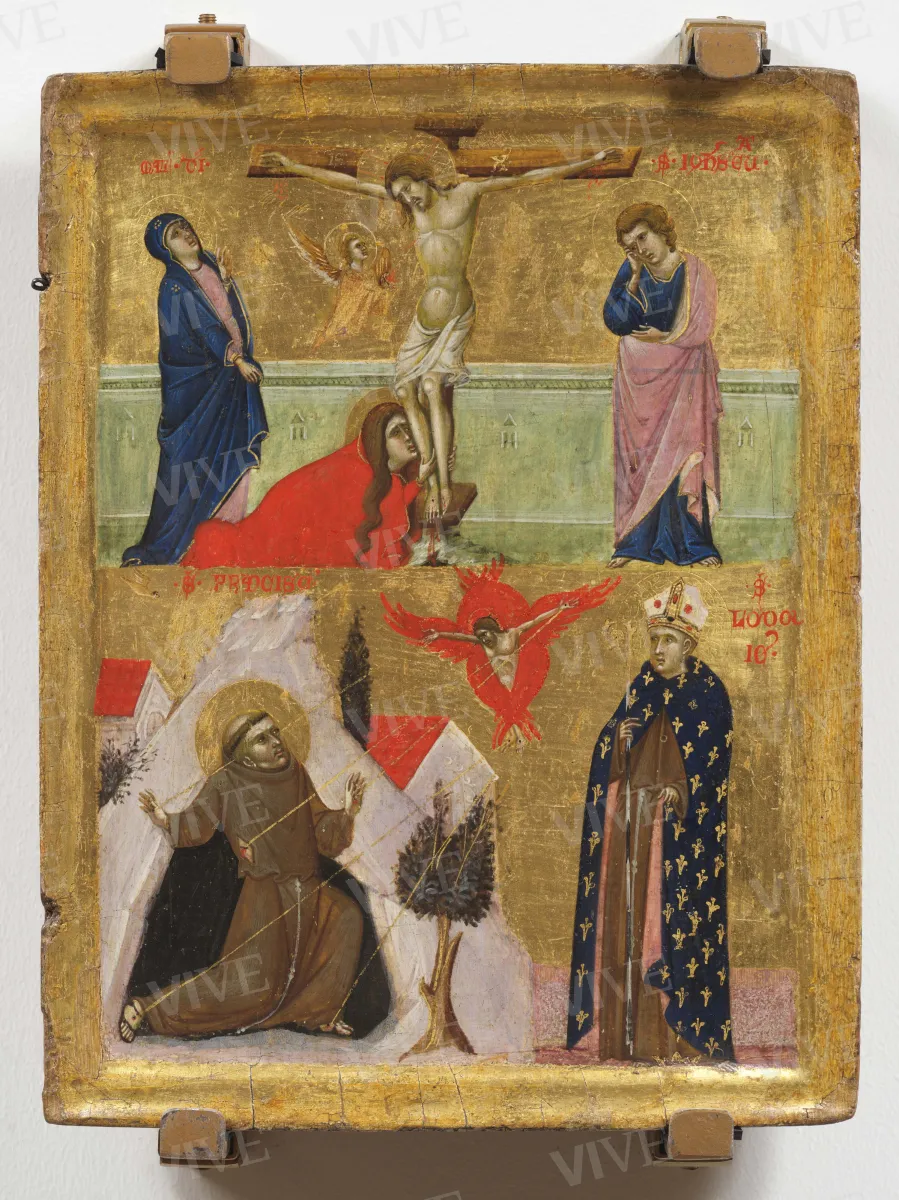

Sterbini Diptych

Master of the Sterbini Diptych Third–fourth decade of 14th century

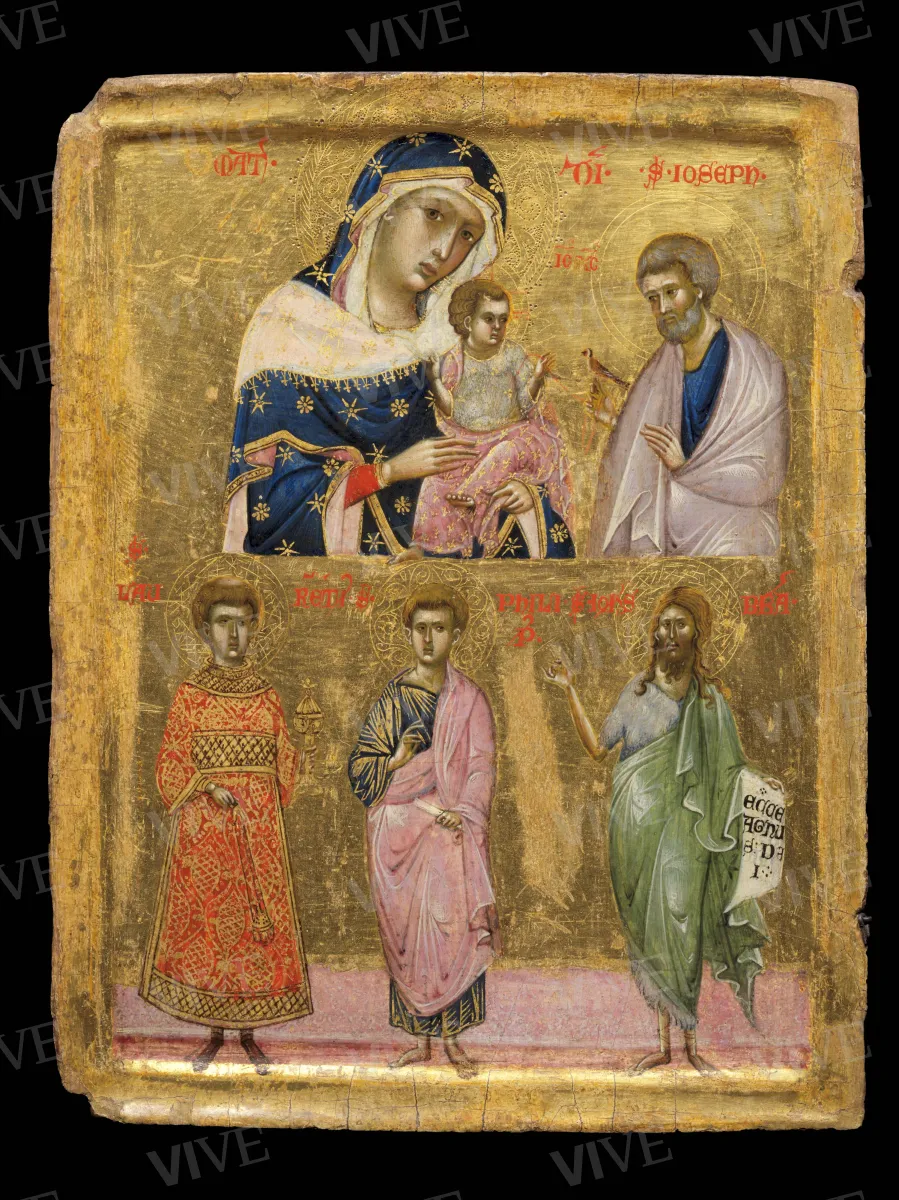

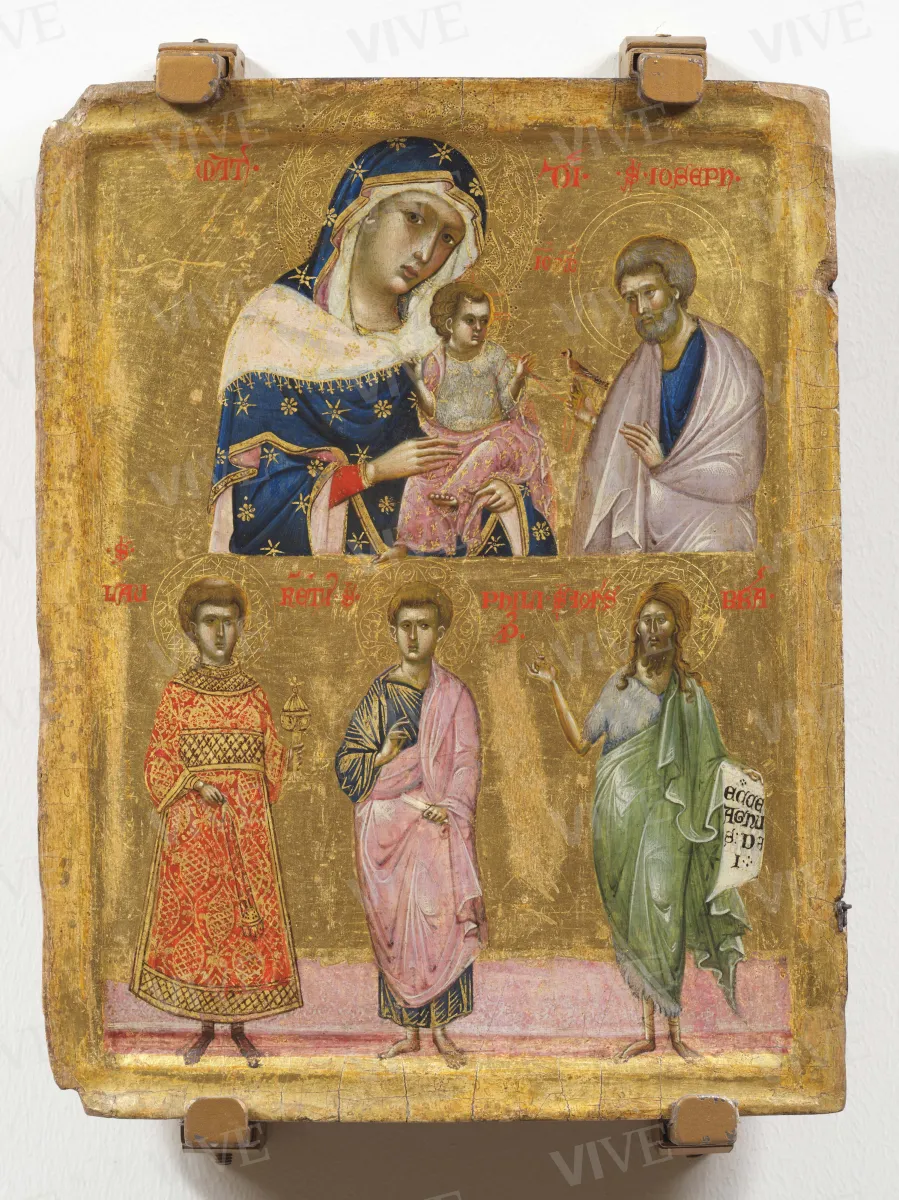

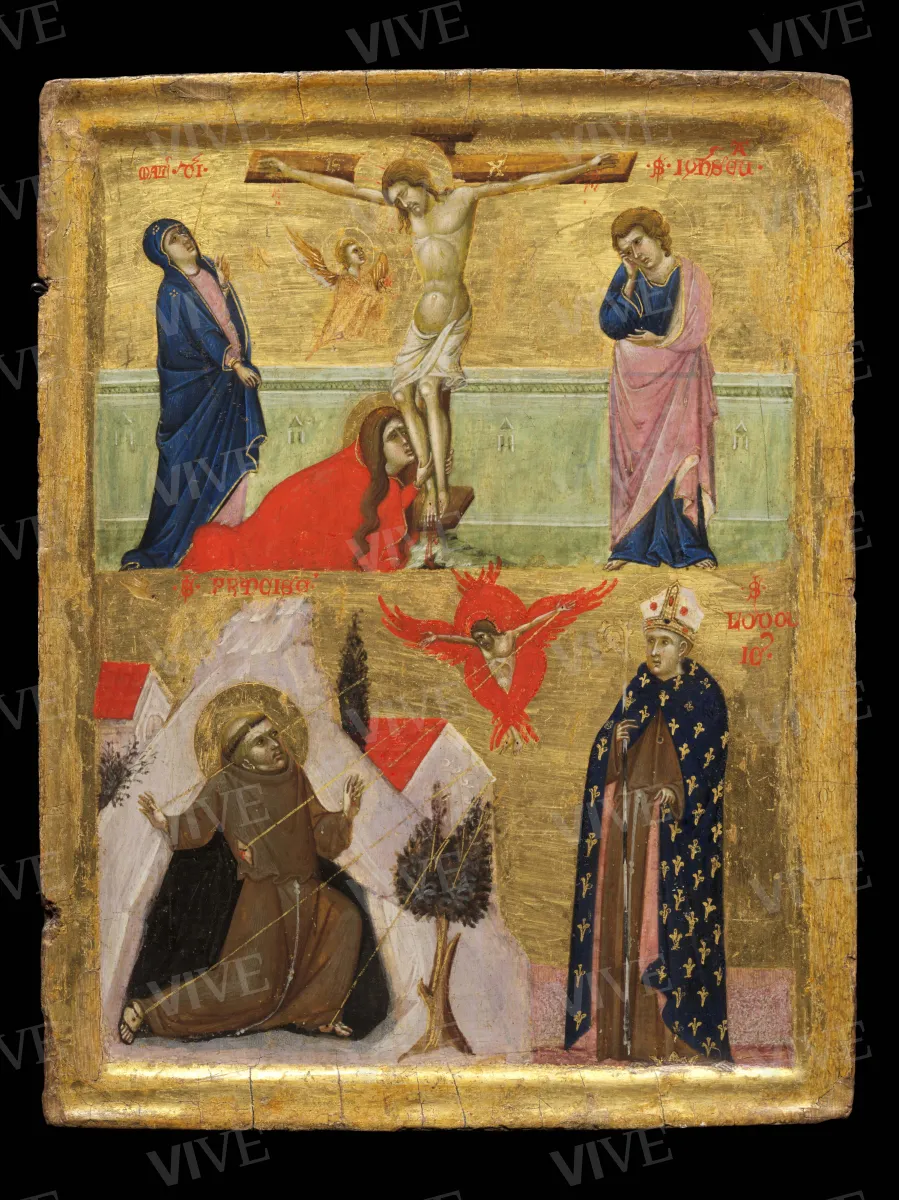

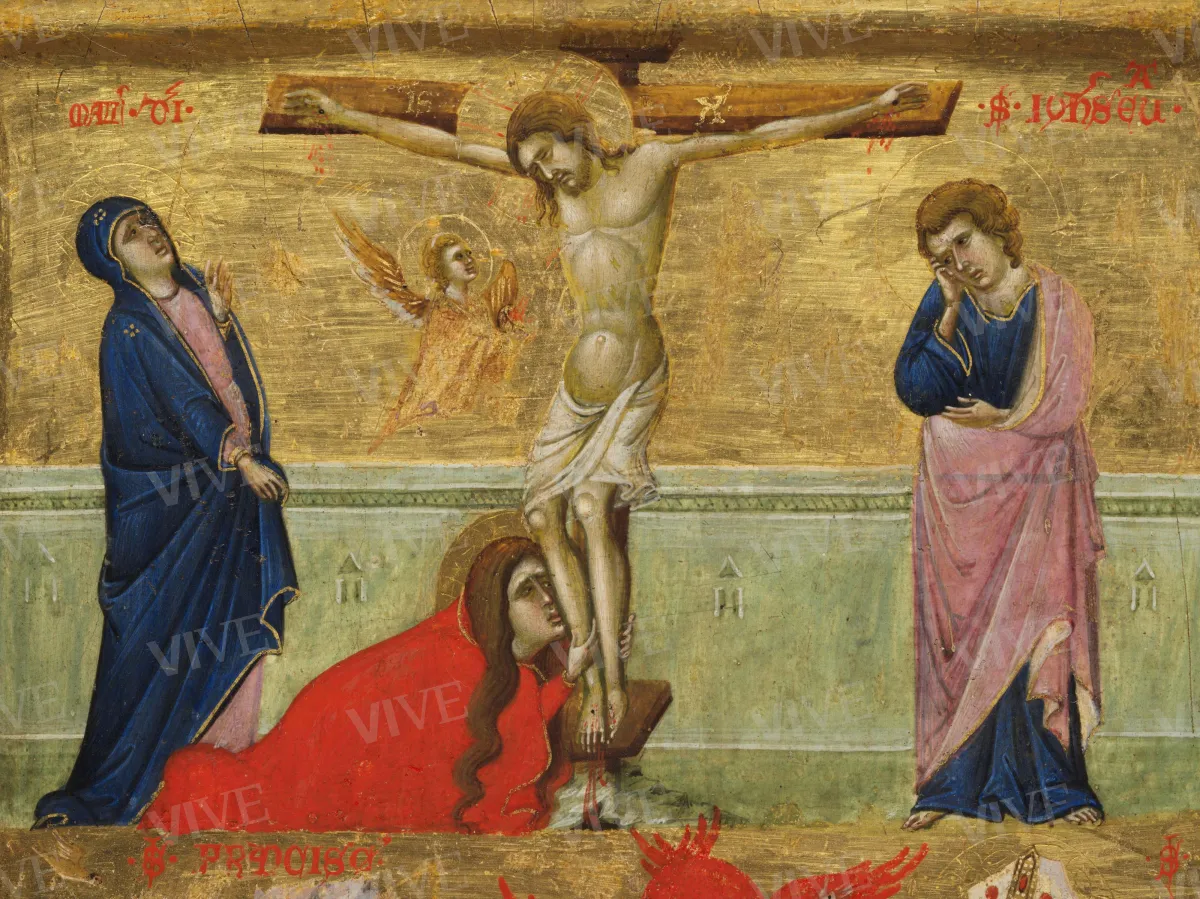

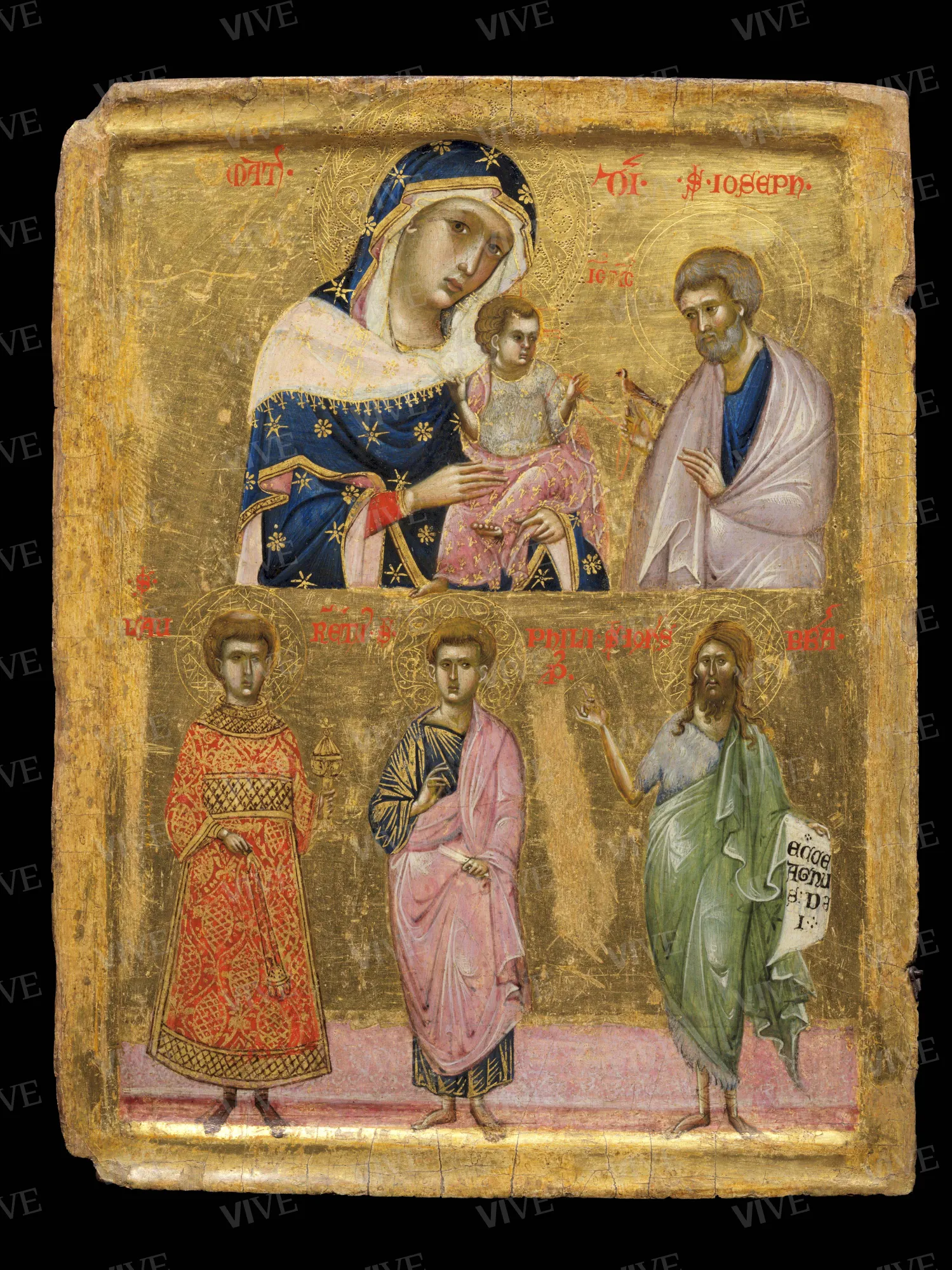

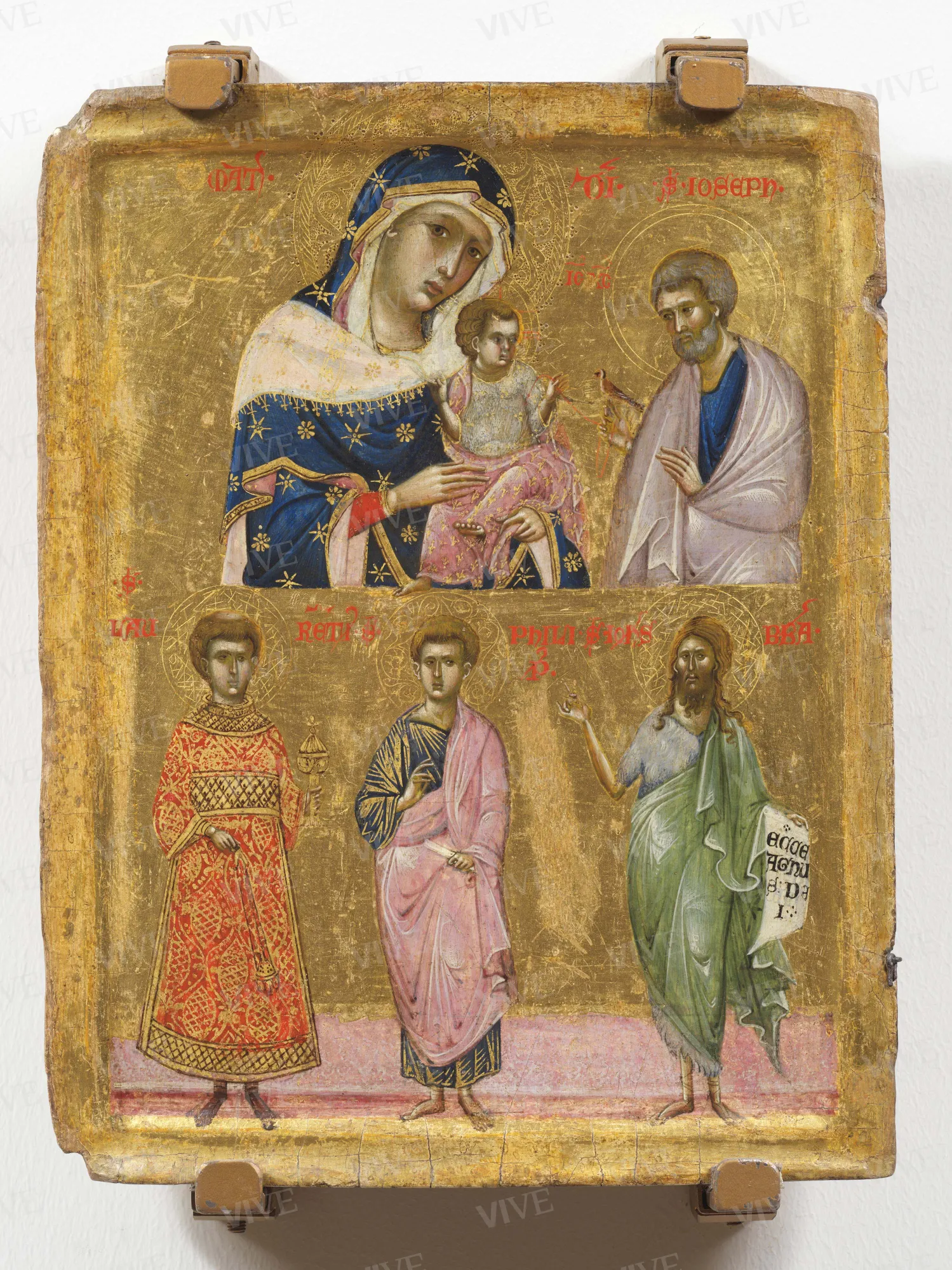

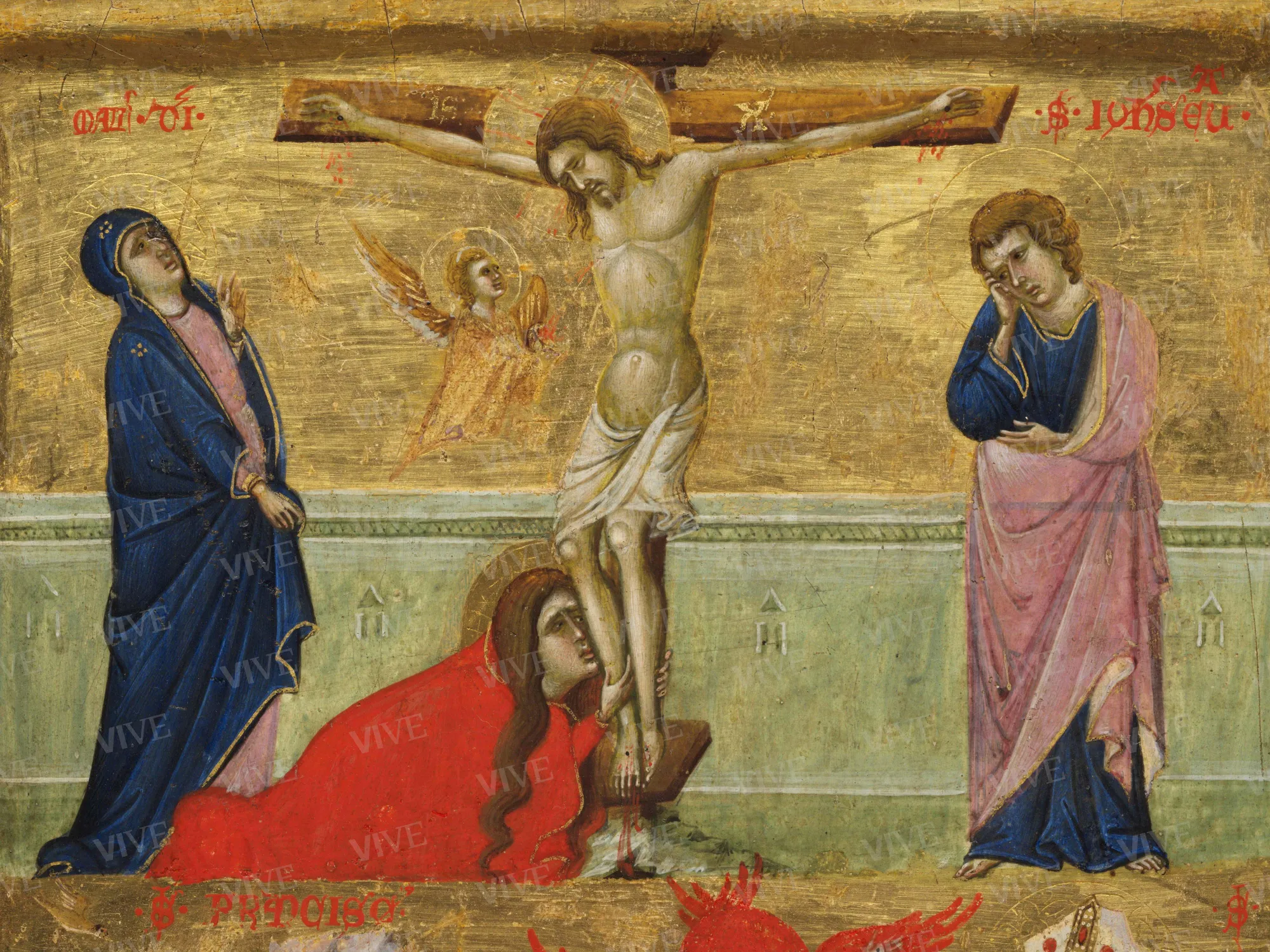

The two panels, originally connected, have two registers where purely iconic elements are juxtaposed with narrative-type inserts. The left panel of the diptych depicts the Virgin in half figure with the Child and Saint Joseph in the act of offering him a robin, and below, in full figure, Saints Lawrence, Philip, and John the Baptist; the right panel, on the other hand, depicts the Crucifixion with the mourners and Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross, while the lower section contains Saint Francis receiving the stigmata and Saint Louis of Toulouse.

The two panels, originally connected, have two registers where purely iconic elements are juxtaposed with narrative-type inserts. The left panel of the diptych depicts the Virgin in half figure with the Child and Saint Joseph in the act of offering him a robin, and below, in full figure, Saints Lawrence, Philip, and John the Baptist; the right panel, on the other hand, depicts the Crucifixion with the mourners and Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross, while the lower section contains Saint Francis receiving the stigmata and Saint Louis of Toulouse.

Details of work

Catalog entry

Because of its quality, but also because of several somewhat atypical features, the diptych immediately led scholars to put forward a series of different attributions based on its stylistic components. The earliest commentators tended to attribute it to central Italy, and posited that the work was by a painter from the Duccio (Jean Paul Richter’s hypothesis reported by Venturi 1905a, p. 201), Cimabua–Assisi (Venturi 1905b), or Roman contexts (Toesca 1927, p. 1041, note 48). The first scholar to take an opposing view was Edward B. Garrison who, by including the Palazzo Venezia diptych in his repertory of Romanesque panel painting, first highlighted the Adriatic culture of the anonymous artist and gave Venice as the likely place of production (Garrison 1949, p. 10 and n. 247). A few years later, on the other hand, Victor Lazarev focused his attention on the Byzantine component of the painting. According to him, Byzantine culture was certainly present, albeit mediated by Western compositional, iconographic, and stylistic concerns (Lazarev 1951, p. 45). The coordinates within which the history of the studies of the diptych under consideration unfolds, therefore, highlight on the one hand a definite Western art tradition, yet on the other hand, they identify certain modes that are typical of paleologic Byzantine art. In fact, these considerations led Antonio Muñoz to use the Sterbini diptych as the opening work in the Italo-Byzantine exhibition in Grottaferrata in 1905 (Muñoz 1906, p. 10). As studies have progressed, other paintings have been compared to the work in the Palazzo Venezia, and they now constitute a small corpus that has come together around the anonymous master who took his name from the Roman diptych. Other works by the master of the Sterbini diptych have been posited, including a Madonna and Child formerly in the Bagnarelli collection in Milan and now of unknown location (Garrison 1949, no. 65), a Madonna and Child formerly in the Kenneth Clark collection recently sold at a Christie’s auction (Lot 34, Old Masters Evening Sale, Christie’s, London July 8, 2021), the triptych with Madonna and Child between Saints Agatha and Bartholomew from the Regional Museum of Messina (Campagna Cicala 2020, pp. 231–232), the Madonna from the Mason Perkins collection now in the Museo del Tesoro della Basilica di San Francesco in Assisi (Palumbo 1973, pp. 7-13), and the altarpiece from the National Trust in Polesden Lacey, England (Corrie 2006). These works, just like the diptych in the Palazzo Venezia, have led to some scholarly embarrassment because of their attribution: the Virgin, formerly the Kenneth Clark Madonna, for example, was previously attributed to Vitale da Bologna; and the formerly Bagnarelli Madonna was attributed by Roberto Longhi to Duccio (Campagna Cicala 2020, p. 233 note 128). A problem that has never been resolved is identifying a center for the activity of the Master of the Sterbini diptych that is able to synthesize the stylistic, compositional, and iconographic components of his works. According to Mojmír Frinta, the anonymous master was possibly active on the Dalmatian coast, while Federico Zeri states that he worked mainly in eastern Sicily where, in Messina, early Aragonese rulers promoted a figurative culture with oriental influences (Frinta 1987; Zeri 1992, pp. 55-56). The most recent studies on the Sterbini diptych have been undertaken by Michele Bacci, who has explained the painting’s “puzzling admixture of Italian and Byzantine elements” by referring to its intentionally heterogeneous character and the concept of “visual hybridity” that would also explain the deliberate use of mixed stylistic models and references in the same work (Bacci 2013; Bacci 2014; Bacci 2017). The great popularity of works such as the Sterbini diptych, whose influence can even be seen in several fourteenth-century Aragonese plates (Cornudella 2014, pp. 11-12), cannot be overstated. The center or geographical area where the Sterbini diptych was produced is most likely Venice, a city not only influenced by oriental contributions but also the spatial interests of contemporary Italian art, and whose author was most likely an itinerant painter of Greek origins (Bacci 2013, p. 211; Bacci 2014). On the other hand, as far as chronology is concerned, it is likely the work dates from between the third–fourth decade of the fourteenth century, but certainly after 1317, the year of the canonization of Saint Louis of Toulouse, who is depicted in one of the panels.

Giampaolo Distefano

Entry published on 12 February 2025

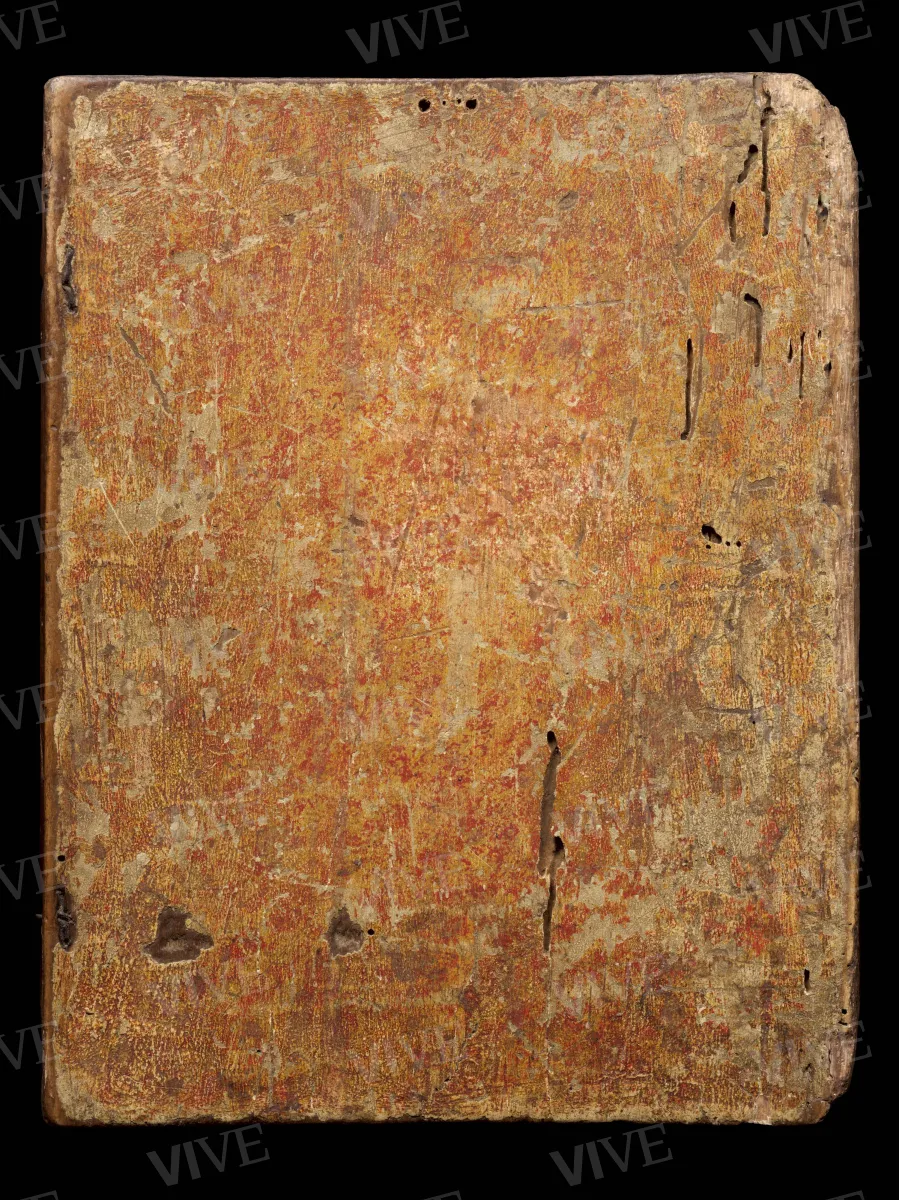

State of conservation

Good.

Inscriptions

Inscriptions on the first panel: “MAT[er] / D[omin]I”; “IC / XC”; “S[anctus] IOSEPH”; “S[anctus] LAV/RE[n]TIVS”; “S[anctus] PHILIP[pu]S”; “S[anctus] IOH[anne]S / B[a]P[tist]A”; “ECCE / AGNU/S DE/I”;

inscriptions on the second panel: “MAT[er] / D[omini]I”; “S[anctus] IOH[anne]S EVA[ngelista]”; “S. FRANCISC[us] “; “S. LODOV/IC[us]”.

Provenance

The diptych, whose provenance is unknown but whose characteristics make it part of a type of image reserved for private worship, was part of the celebrated collection of Giulio Sterbini, a trusted man of Pope Leo XIII, known especially for paintings from the Byzantine context (Morozzi 2006). After briefly belonging to the Lupi collection, the diptych was added to the collection of Giovanni Armenise. Giovanni Armenise bequeathed the work to the Italian state in 1940.

Exhibition history

Grottaferrata, abbey of San Nilo, Esposizione di arte italo-bizantina, 1904–1905;

Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, Cipro e l'Italia al tempo Bisanzio. L'Icona Grande di San Nicola tis Stégis del XIII secolo restaurata a Roma, June 23–July 26, 2009;

Turin, Reggia di Venaria Reale, Restituzioni 2018. Tesori d’arte restaurati, March 28–September 16, 2018.

References

Venturi Adolfo, Dittico attribuito a Cimabue, nell’esposizione di Grottaferrata, in «L’Arte», 8, 1905, pp. 199-201 (Venturi 1905a);

Venturi Adolfo, La quadreria Sterbini in Roma, in «L’Arte», 8, 1905, pp. 422-440 (Venturi 1905b);

Muñoz Antonio, L’art byzantin à l’exposition de Grottaferrata, Roma 1906, p. 10;

Toesca Pietro, Storia dell’arte italiana. Il Medioevo, 2 voll., Torino 1927;

Museo di Palazzo Venezia. Catalogo. 1. Dipinti, Santangelo Antonino (a cura di), Roma 1947, pp. 5-6;

Hermanin Federico, Il Palazzo di Venezia, Roma 1948, p. 409;

Garrison Edward B., Italian Romanesque Panel Paintings. An Illustrated Index, Firenze 1949, p. 10 e n. 247;

Lazarev Victor, Über eine neue Gruppe byzantinisch-venezianischer Trecento-Bilder, in «Art Studies», VIII, 1951, pp. 3-3 (ora in Id., Studies in Byzantine Painting, London 1995, pp. 25-72, p. 45);

Palumbo Giuseppe, Collezione Federico Mason Perkins, Roma 1973, pp. 7-13;

Frinta Mojmír Svatopluk, Searching for an Adriatic Painting Workshop with Byzantine Connection, in «Zograf», XVIII, 1987, pp. 12-20;

Zeri Federico, in Campagna Cicala Francesca, Zeri Federico (a cura di), Messina. Museo Regionale, Palermo 1992, pp. 55-56;

Corrie Rebecca, The Polesden Lacey Triptych and the Sterbini Diptych: A Greek Painter between East and West, in Jeffreys Elizabeth (a cura di), Proceedings of the 21th International Congress of Byzantine Studies (Londra, 21-26 agosto 2006), London 2006, vol. III, pp. 47-48;

Morozzi Luisa, Da Lasinio a Sterbini, "primitivi" in una raccolta romana di secondo Ottocento, in Adembri Benedetta (a cura di), Aei mnēstos. Miscellanea di studi per Mauro Cristofani, Firenze 2006, pp. 908-916;

Bacci Michele, Some Thoughts on Greco-Venetian Artistic Interactions in Fourteenth and Early-Fifteenth Centuries, in Eastmond Antony, James Liz (a cura di), Wonderful Things: Byzantium Through Its Art: Papers from the Forty-Second Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies (Londra, 20-22 marzo 2009), Farnham 2013, pp. 203-227;

Bacci Michele, Veneto-Byzantine “hybrids”: towards a Reassessment, in «Studies in Iconography», XXXV, 2014, pp. 73-106 (p. 97);

Cornudella Rafael, The Master of Baltimore and the Origin of Italianism in Catalan Painting of the Fourteenth Century, in «The Journal of the Walters Art Museum», LXXII, 2014, pp. 7-22;

Bacci Michele, Un ibrido di successo: il “dittico Sterbini”, la Madonna “dal risvolto bianco” e la Vergine Konevskaja, in Bock Nicolas, Foletti Ivan, Tomasi Michele, Survivals, revivals, rinascenze. Studi in onore di Serena Romano, Roma 2017, pp. 469-483 (con bibliografia);

Campagna Cicala Francesca, Pittura medievale in Sicilia, Messina 2020.