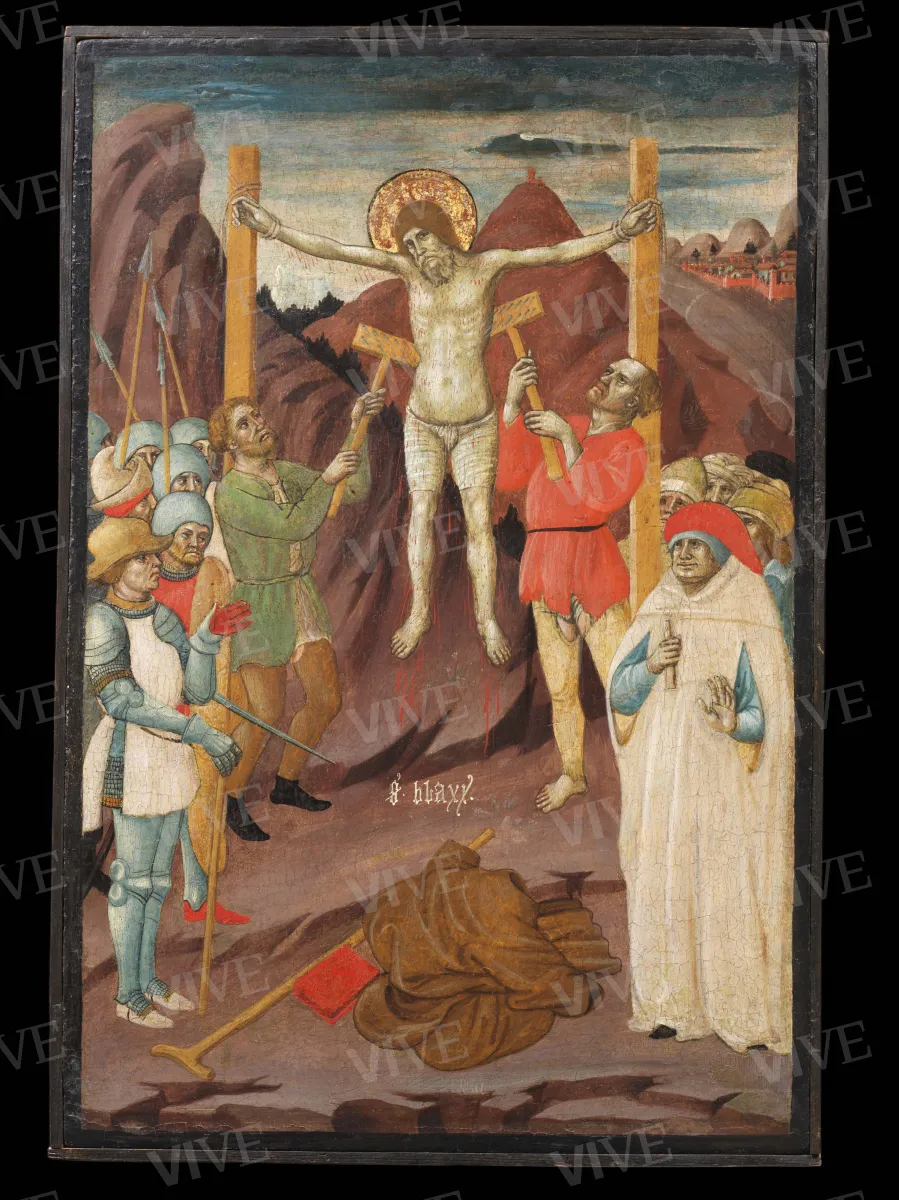

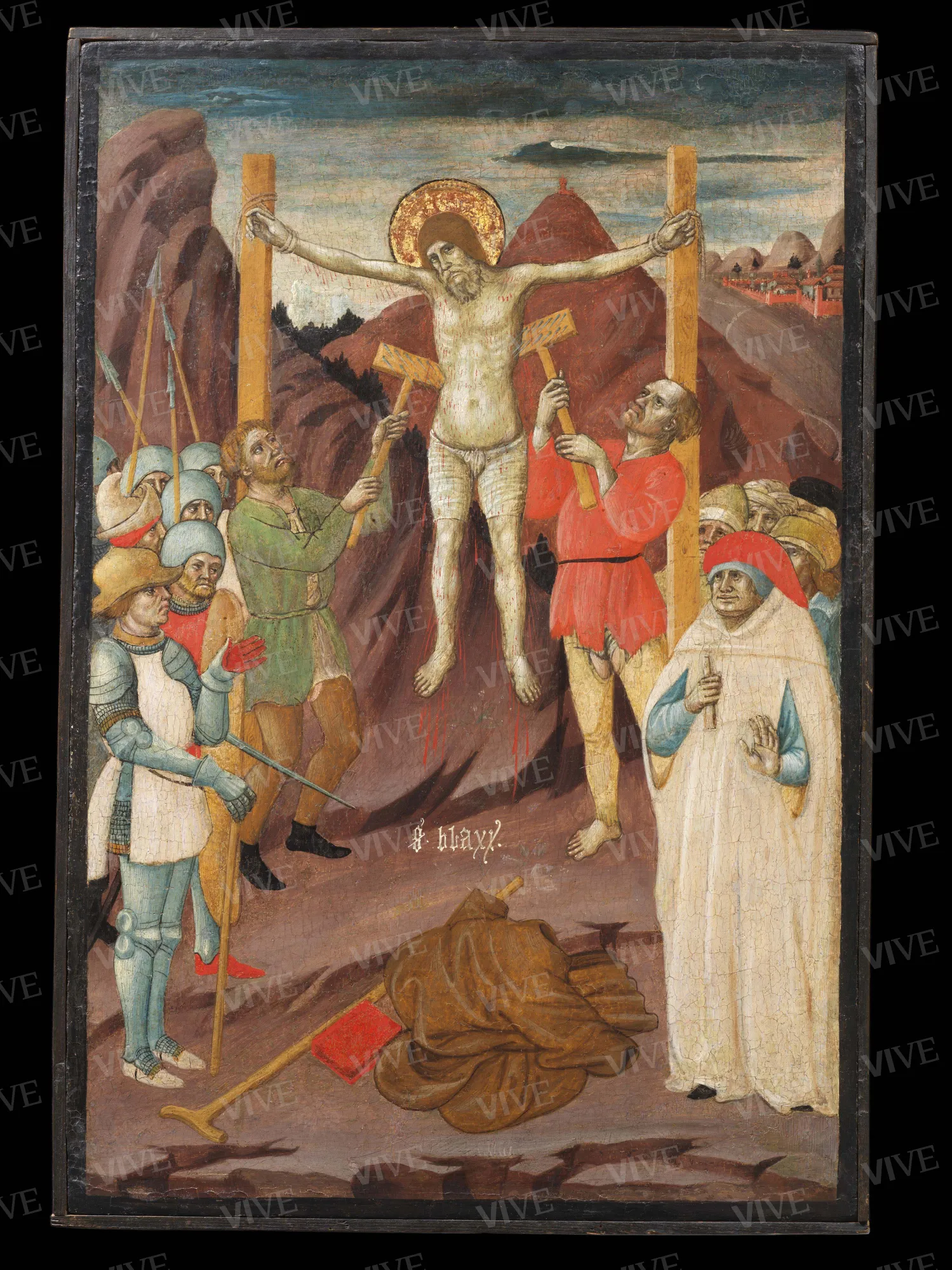

Saint Blaise Tortured with Iron Combs

Giovanni Antonio Bellinzoni da Pesaro C. 1440-1450

The small panel depicts one of the legendary martyrdoms suffered by Blaise, bishop of Sebaste in Armenia. One of the most venerated saints of the Christian Middle Ages: the torture with iron combs, inflicted on him in a vain attempt to induce him to apostasy. Together with two other misplaced panels depicting the Martyrdom of the Millstone and the Beheading, and other unidentified panels, this panel formed a cycle dedicated to the life of Saint Blaise included in an altarpiece by Giovanni Antonio Bellinzoni from Pesaro, perhaps intended for the chapel of the Dalmatian immigrants in the church of San Domenico in Ancona.

The small panel depicts one of the legendary martyrdoms suffered by Blaise, bishop of Sebaste in Armenia. One of the most venerated saints of the Christian Middle Ages: the torture with iron combs, inflicted on him in a vain attempt to induce him to apostasy. Together with two other misplaced panels depicting the Martyrdom of the Millstone and the Beheading, and other unidentified panels, this panel formed a cycle dedicated to the life of Saint Blaise included in an altarpiece by Giovanni Antonio Bellinzoni from Pesaro, perhaps intended for the chapel of the Dalmatian immigrants in the church of San Domenico in Ancona.

Details of work

Catalog entry

The son of Giliolo di Giovanni Bellinzoni, an artist from Parma whose works have yet to be definitively attributed, Giovanni Antonio was probably born in Pesaro in the 1410s. His life was spent between his hometown, where records show his presence from 1437, and Ancona, the residence of his wife Caterina Massioli. Early documentation indicates a collaboration between father and son, though no surviving works can be definitively dated to that period. However, it includes artworks such as the panels of the polyptych from Sant’Ermete in Gabicce Monte (Pesaro, Museo Civico) and the frescoes in the apse of San Francesco in Rovereto near Saltara. The decoration, comprising frescoes and an altarpiece, commissioned in 1441 for a chapel in the church of San Francesco delle Scale in Ancona by Giliolo and Giovanni Antonio, has been lost. Around the mid-fifteenth century, Giovanni Antonio painted two polyptychs in Sant’Esuperanzio in Cingoli, and also frescoed a chapel, decorated with fragmentary elements dating back to the 1440s. The jubilee year of 1450 can be seen in one of the pages that Giovanni Antonio, in a rare foray into the field of illumination, decorated with pen and ink in a book of hours probably destined for Ancona. This book was largely decorated by Antonio di Domenico, a Florentine painter who moved to Ancona. An equally unique piece is a two-faced painted cross now in the Metropolitan Museum (Lehman Collection, inv. 1975.1.25). It is only in 1462, the date inscribed along with the artist’s signature on the Madonna della Misericordia in Santa Maria dell’Arzilla in Candelara di Pesaro, that we begin to see works with definite chronological references. The following year saw the creation of the now dismembered triptych with Saint Mark in the center, perhaps for the church of Santa Maria di San Marco in Pesaro, whose panels are now in Oxford, Avignon, and the Ruffo della Scaletta collection. The works destined for Sassoferrato, the grandiose polyptych of the abbey of Santa Croce (Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche), and the frescoes in Santa Chiara, are from the second half of the same decade, around the time of the 1467 fresco with Saint Blaise in the same abbey church. The last years of the painter, who died in 1475 perhaps in Ancona, are better documented thanks to the panel of San Donnino di Tavullia, dated 1472, and the horizontal altarpiece with the Madonna and Child with Saints (including the mysterious Saint Aiuto) formerly in Pesaro at Altomani & Sons and dated 1473: a clear sign of the progressive rigidity of form that Bellinzoni adopted in his later works.

The panel, with its horizontal grain support, is well-preserved and framed by modern wooden strips that conceal its thickness. It depicts an episode from the legend of Saint Blaise, bishop of Sebaste in Armenia, who lived between the third and fourth centuries, as recounted in the thirteenth century in Jacopo da Varazze’s Legenda Aurea (Golden legend): his martyrdom with iron combs, used to force him to renounce his faith. The instrument of his torture later became one of the saint’s recognized iconographic attributes. The scene is set in a barren mountainous landscape, with a small city visible in the background to the right. The saint, suspended by his hands from two poles, is depicted wearing only a loincloth and brown cap, while his other garments—a brown tunic, a stick, and a red book—are shown lying on the ground in the foreground. The torture is conducted by two executioners and observed on the left by several soldiers led by a commander, and on the right by other figures in hats and turbans, partially hidden by a richly dressed man, very likely the magistrate responsible for Blaise’s condemnation, holding a scroll of the sentence.

The painting was returned to Bellinzoni through the efforts of Federico Zeri, who initially conveyed his intuition with Antonino Santangelo in 1947. Shortly thereafter, Zeri himself published the work in 1948, along with two other connected paintings of similar dimensions portraying other moments in the saint’s life: the Martyrdom of the Millstone, first published in 1927 by Raimond Van Marle as a work very reminiscent of Pisanello, and seen by him initially on the Roman market, then in the Volterra collection in Florence; and the Beheading, documented in Florence in the Philip J. Gentner collection, previously in Rome during the 1940s, and subsequently sold at auction twice (Christie’s, Rome, May 26, 1981, lot 237, and Hampel, Munich, December 6, 2012, lot 392). Between these two auctions, it was held by Altomani & Sons, Pesaro. There is no information about the existence of a fourth panel, possibly due to a misunderstanding, which is only mentioned by Santangelo in 1947, who noted that “it appeared in the [Achillito] Chiesa sale.

The three small panels are likely from a narrative altarpiece, symmetrically arranged in two registers around a figure of Saint Blaise, which may have been carved in wood or painted. A possible candidate for the central compartment is a holy bishop on a throne, although its dimensions are unknown and it lacks any special attributes for identification. This bishop is part of a Perugian collection and was published by Mauro Minardi (Minardi 2003, fig. 3), who dates it to a later period. The vertical format and large size of the panels suggest that they were part of an articulated complex, possibly comprising eight episodes. Additionally, the horizontal grain of the wood is a feature common to predellas.

The presence of raised plaster on the upper and right-hand sides of the Beheading, contrasted with abundant traces of smooth plaster on the other sides—along with the original gilding still intact on the left—indicates that overlapping strips of a frame were present on the top and right. These strips were plastered together with the support prior to painting, suggesting that the compartment occupied the upper right corner of the dismembered altarpiece. At the bottom left, simple golden stripes separated the panel from the adjacent ones, reflecting a more understated subdivision compared to the twisted columns observed in examples from the Marches, which feature multilobed round arches inscribed within the panel outlines. In this case, the format was simply rectangular. The accounts of Saint Blaise's life typically conclude with his beheading, often depicted alongside angels raising his soul to heaven. Occasionally, these accounts include the burial scene, which would typically be located in the lower right corner, below the depiction of the beheading. The original provenance of the altar frontal remains undetermined; however, certain indicators suggest a connection to Ancona, a city associated with Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro for many years. In 2008, I proposed (Mazzalupi 2008) that this altarpiece was commissioned by the Schiavoni di Ancona confraternity, which maintained an altar in the church of San Domenico in 1444. This secular brotherhood, established following the official recognition of the Slavic community by the city in 1439, and its chapel in the church of the Predicatori, or preachers, frequently received bequests from immigrants across the Adriatic. It is conceivable that during the 1440s, this chapel was furnished with a distinguished altarpiece honoring the patron saint, and that the commission was awarded to the most prominent painter active in the city at that time. Supporting this hypothesis is the observation that the beheading scene contains a figure adorned with a prominent red headdress and draped in a large black cloak over a white tunic, resembling the canonical dress of the Dominicans, which may serve as a homage to the order of preachers officiating in the church of Ancona.

Regardless of its accuracy, the group of paintings can be attributed to an early period in Giovanni Antonio’s career. Federico Zeri (1948) initially proposed a chronological framework, suggesting that the three panels were “very similar” to the predella of the Sassoferrato polyptych which lacks a definite date but is not believed by him to predate 1450. Subsequently, Paride Berardi, possibly with Zeri’s endorsement, repositioned the panels towards the beginnings of Giovanni Antonio’s career, potentially within the 1330s, aligning them with the remains of the Gabicce polyptych, the frescoes of Saint Francis in Rovereto di Saltara, the Saint John the Baptist and Saint Septimius in the Museo di Palazzo Venezia (inv. 10215 and 10216), and a predella featuring the Apostles in a private collection (Berardi 1988). Berardi suggested that the predominant Emilian influence, characterized by strong expressionist elements from painters such as Jacopo di Paolo and Giovanni da Modena, “without evident traces of local contributions,” might indicate the involvement of Giovanni Antonio’s father Giliolo, whose works remain unidentified. Mauro Minardi (2014) generally agrees with this analysis, although I feel his anticipation to around 1430 is unconvincing. The attribution to Giovanni Antonio’s early period can be corroborated by observing the vibrancy and originality of the palette, which in his later years becomes more subdued and conventional. Additionally, the drapery highlighted by luminous crests shows no signs of the flattening observed in the latter half of the century.

Matteo Mazzalupi

Entry published on 27 March 2025

State of conservation

Good.

Inscriptions

On the rock at the saint’s feet, painted in white: “s(anctus) blaxi(us).”

Provenance

Rome, Giulio Sterbini, until 1911;

Rome, Tommaso Lupi;

Rome, Collezione Giovanni Armenise, until 1940;

donated by the latter to the Italian State, 1940.

References

Santangelo Antonino (a cura di), Museo di Palazzo Venezia. Catalogo. 1. Dipinti, Roma 1947, pp. 33-34;

Zeri Federico, Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro, in «Proporzioni», II, 1948, pp. 164-167;

Kaftal George, Iconography of the Saints in Central and South Italian Schools of Painting, Florence 1965, coll. 225-226;

Berardi Paride, Giovanni Antonio Bellinzoni da Pesaro, Fano 1988, pp. 42-46;

Minardi, in Donati Angela (a cura di), Il potere, le arti, la guerra. Lo splendore dei Malatesta, catalogo della mostra (Rimini, Castel Sismondo, 3 marzo-15 giugno 2001), Milano 2001, p. 204, n. 65;

Minardi, in Altomani & Sons, catalogo della mostra (Maastricht, 2003), Bologna 2003, pp.n.n., n. 2;

Mazzalupi Matteo, Pittori ad Ancona nel Quattrocento, in De Marchi Andrea, Mazzalupi Matteo (a cura di), Pittori ad Ancona nel Quattrocento, Milano 2008, pp. 97-195, 224-295, 322-331;

De Marchi Andrea, La pala d’altare. Dal polittico alla pala quadra, dispense del corso tenuto presso l’Università di Firenze nell’a.a. 2011-2012, Firenze 2012, p. 123;

Minardi, in Chiodo Sonia, Padovani Serena (a cura di), The Alana Collection, Newark, Delaware, USA, III, Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century, Florence 2014, pp. 118-124, n. 17;

Capriotti Giuseppe, The Painting Owned by the Schiavoni Confraternity of Ancona and the Wooden Compartments with Stories of St Blaise by Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro, in «Il capitale culturale. Supplementi», 7, 2018, pp. 187-209;

Natale Mauro (a cura di), Federico Zeri, Roberto Longhi. Lettere (1946-1965), Cinisello Balsamo 2021, pp. 59, 66.