Saint Benedict’s Cross

Rhenish goldsmith 12th century

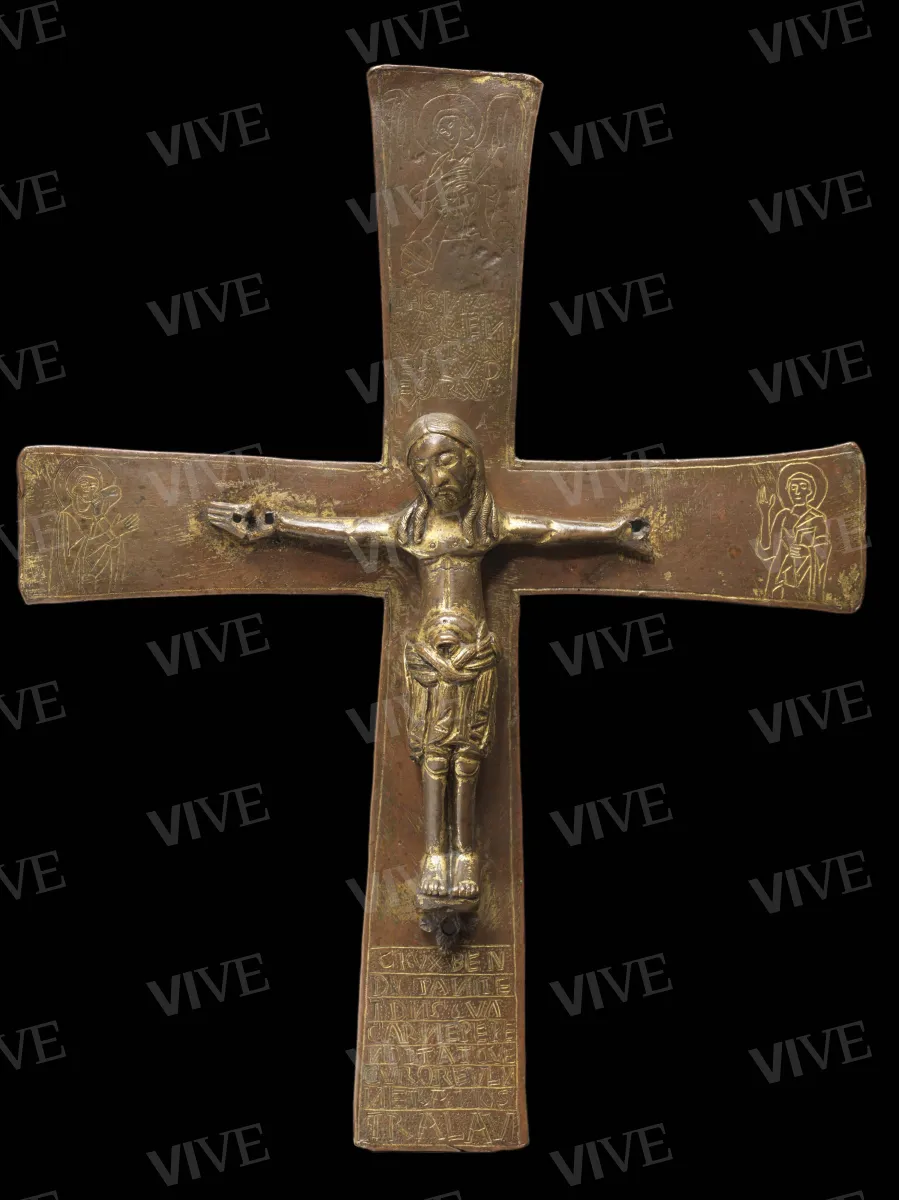

On the recto, the supporting cross features an angel with thurible at the top, the Virgin and Saint John at the sides, and two inscriptions above and below Christ; on the verso, we have Saint Benedict in the center, and the symbols of the evangelists in the heads of the cross. The figure of Christ, resting on a suppedaneum supported by a shelf with a tripartite termination, is cast in three dimensions, his head inclined forward, his hair falling forward, and his loincloth tied at its central point with knot. The original gilding of the Christ figure and the cross is only partially preserved.

On the recto, the supporting cross features an angel with thurible at the top, the Virgin and Saint John at the sides, and two inscriptions above and below Christ; on the verso, we have Saint Benedict in the center, and the symbols of the evangelists in the heads of the cross. The figure of Christ, resting on a suppedaneum supported by a shelf with a tripartite termination, is cast in three dimensions, his head inclined forward, his hair falling forward, and his loincloth tied at its central point with knot. The original gilding of the Christ figure and the cross is only partially preserved.

Details of work

Catalog entry

The cross falls within a group of works that are similar in material and technique—bronze, partly gilded and engraved, and cast figure of Christ—but with evident stylistic differences. In studies—mainly those of Peter Bloch and Andrea Del Grosso—that have examined such works and that constitute the two most important corpora, however, the Palazzo Venezia specimen is not listed. On the recto, the supporting cross follows the classical iconography with mourners and angel while an eight-line inscription in capital letters is placed in the lower arm. As noted for the first time in Distefano 2023, it reproduces, with some grammatical and paleographic uncertainty, the opening lines of the hymn “Crux benedicta nitet/ Dominus qua carne pependit/ Atque cruore suo vulnera lavat,” attributed to the poet Venantius Fortunatus, who lived in the sixth century but whose work became very popular in the Middle Ages, especially in the Carolingian period (Filosini 2013). However, the full-length engraved depiction of Saint Benedict on the verso, who is also identified by a titulus, is rare in this type of work. Bloch’s repertory, for example, only includes the Zurich cross whose verso contains a haloed figure with a crozier (Bloch 1992, p. 102, no. I G 2) and the Langenargen museum example, which has an abbot accompanied by the legend “Gebo abba” (Bloch 1992, p. 198, IV B 4). There are different opinions regarding the figure of Christ, who has been given full metal limbs and head but a hollow body from the shoulders to the lower hem of the loincloth. His centrally parted hair falls over his shoulders in five tubular-like locks. This particular hair style and texture, achieved through the use of subtle parallel incisions, can also be found in Germanic specimens dating from the eleventh century. In Bloch’s repertory, on the other hand, the conformation of the loincloth that was used to classify the more than six hundred crucifixes in his corpus. The Palazzo Venezia crucifix’s loincloth recalls some of the characteristic elements of these figures without, however, fully falling into any of the different categories. In fact, the loincloth has beaded edges typical of a number of bronze figures attributed to the Westphalia region in the first half of the twelfth century, such as, for example, the Christ in the Hessische Landesmuseum in Darmstadt (Bloch 1992, no. I B 7, p. 6), whereas the cross knot recalls a group of crucifixes from the Middle Rhine and Lower Saxony dating to the mid-twelfth century (Bloch 1992, pp. 125-136, nos. I L 1/24). These considerations lead some to attribute the Christ figure to a twelfth-century workshop in Rhineland or Lower Saxony, although it should also be borne in mind that these bronzes—not necessarily mass-produced and therefore sometimes difficult to classify (Peroni 2006a, p. 36)—also led to a slew of more or less faithful replicas in thirteenth-century north-central Italy (Hueck 1982, pp. 173–174; Del Grosso 2010). The clumsy holes securing the figure of Christ to its support suggest that the two parts were put together at a later date (Vigliarolo 2009, p. 253), and would thus imply a different origin. Indeed, some peculiarities of the supporting cross seem to indicate that it was made in twelfth-century central Italy. The upper portion of the cross, for example, which is generally reserved for an archangel with loros in crosses from the imperial period, has here been given an angel with thurible, which is typical of a number of specimens attributed to twelfth-century Tuscany, such as the one held in the Museo Statale d’Arte in Arezzo (Peroni 2006b). The style of the engraved figures, which can be described as concise and lively, recalls characteristics of central Italian miniatures between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (Garrison 1993). Moreover, some have drawn parallels between this figure and specimens in the staurotheke of the Roman church of Santa Maria in Campitelli, which were signed by the goldsmith Gregorio. As such, along with other epigraphic evidence, this would allow us to date it more precisely to the first quarter of the twelfth century (Montorsi 1980, pp. 136-148; Vigliarolo 2009, p. 255). The stylistic and figurative components of the supporting cross, therefore, reflect a central Italian artistic context, which would also explain the full-length Saint Benedict on the verso.

The provenance of the Cross of Saint Benedict was unknown when it entered the museum in 1922. The recent discovery of two drawings reproducing this work’s recto and verso, which are part of the graphic materials of Jean-Baptiste Louis George Seroux-d’Agincourtd at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vat. lat. 9846, ff. 40r, 45v), has made it possible to partially reconstruct its early history (Distefano 2023). Indeed, both folios, which are dated to about the end of the eighteenth century, state that it was part of the collections of the Collegio Romano, where other medieval artifacts were also held (Distefano 2023).

Giampaolo Distefano

Entry published on 12 February 2025

State of conservation

Good.

Inscriptions

On the recto, below the angel with thurible: “IHSИA/SAREИ/VSRN/ESIVD/EORV/M”;

on the recto, below the crucifix: “CRUXBEN[E]/DICTAИITE/TDИSQVA/CARИEPEPE/ИDITATQVE/CVROREVLV/ИERAИOS/TRALAV[AT]”;

on the verso, below the figure of Saint Benedict: “S [reversed forward] BEИE/DICTU”.

Provenance

Rome, Collegio Romano;

purchased 1922.

Exhibition history

Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo di Venezia, Cipro e l’Italia al tempo di Bisanzio. L’Icona Grande di San Nicola tis Stegis del XIII secolo restaurata a Roma, June 23-July 26, 2009.

References

Hermanin Federico, Il Palazzo di Venezia, Roma 1948, p. 299;

Montorsi Paolo, Cimeli di oreficeria romanica. Un bronzetto modenese e due reliquiari romani, in Romanini Angiola Maria (a cura di), Federico II e l’arte del Duecento italiano. Atti della III settimana di studi di Storia dell’arte medievale dell’Università di Roma (1978), II, Galatina 1980, pp. 127-152;

Hueck Irene, L’oreficeria in Umbria dalla seconda metà del secolo XII alla fine del secolo XIII, in Pirovano Carlo, Porzio Francesco, Selvafiorita Ornella (a cura di), Francesco d’Assisi. Storia e arte, III, catalogo della mostra (Assisi, Sacro Convento, 1982), Milano 1982, pp. 168-187;

Bloch Peter, Romanische Bronzekruzifixe, Berlin 1992;

Garrison Edward B. , Twelfth-Century Initial Styles of Central Italy: Indices for the Dating of Manuscripts. II. Materials, in Garrison Edward B., Studies in the History of Medieval Italian Painting, III, London 1993, pp. 33-83;

Peroni Adriano, L’altare portatile di san Geminiano patrono di Modena e le croci astili al di qua e al di là dell’Appennino. Temi e problemi storiografici dell’“ars sacra”, in Peroni Adriano, Piccinini Francesca (a cura di), Romanica. Arte e liturgia nelle terre di San Geminiano e Matilde di Canossa, catalogo della mostra (Modena, Musei del Duomo, 16 dicembre 2006-1 aprile 2007), Modena 2006, pp. 23-49;

Peroni, in Peroni Adriano, Piccinini Francesca (a cura di), Romanica. Arte e liturgia nelle terre di San Geminiano e Matilde di Canossa, catalogo della mostra (Modena, Musei del Duomo, 16 dicembre 2006-1 aprile 2007), Modena 2006, pp. 145-147, n. 8;

Vigliarolo Luca, in Eliades Ioannis A. (a cura di), Cipro e l’Italia al tempo di Bisanzio. L’Icona Grande di San Nicola tis Stegis del XIII secolo restaurata a Roma, catalogo della mostra (Roma, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo di Venezia, 23 giugno-26 luglio 2009), Atene 2009, pp. 252-255, n. A.10;

Del Grosso Andrea, Croci processionali toscane: il tipo a bracci patenti nel Medioevo, Poggio a Caiano (Po) 2010;

Filosini Stefania, Tra poesia e teologia: gli Inni alla Croce di Venanzio Fortunato, in Gasti Fabio, Cutino Michele (a cura di), Poesia e teologia nella produzione latina dei secoli IV-V, atti della X Giornata Ghisleriana di Filologia Classica (Pavia, 16 maggio 2013), Pavia 2013, pp. 107-131;

Giampaolo Distefano, «Crux benedicta nitet». A proposito di una croce bronzea poco nota del Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia, in «RIASA-Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte», 2023, pp. 157-171.