Our Lady of the Walnut

Milieu Umbria-Abruzzo 1515–1530

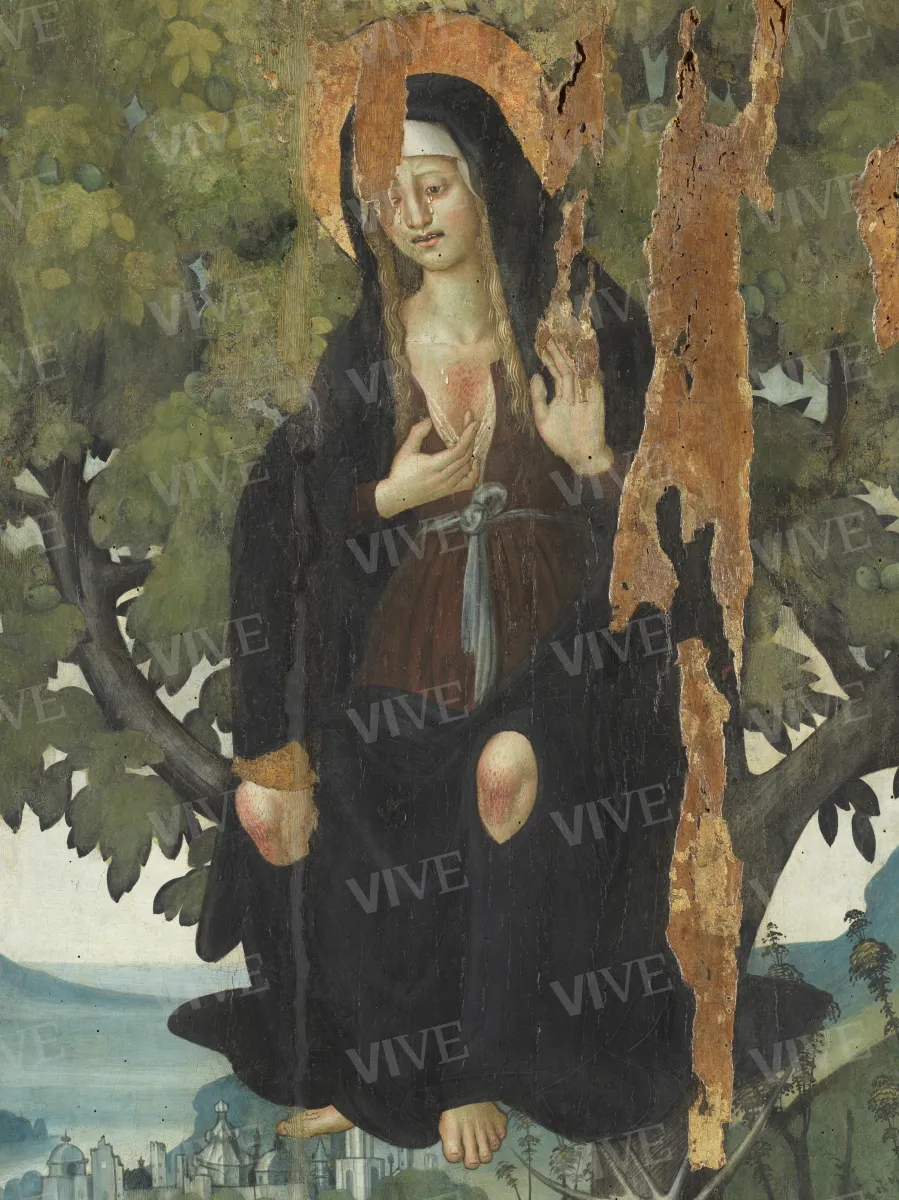

The painting illustrates a miraculous event that reportedly occurred on June 10, 1505, in San Polo Sabino, within the province of Rieti. According to historical sources, the weeping Virgin, attired in black akin to the tertiaries of the Order of Servants of Mary and seated on a walnut tree, appeared to a young girl. The Virgin revealed wounds inflicted by human sins and directed the girl to admonish the populace to engage in penance and adhere to the faith’s precepts. This artwork, possibly created within the circle of Saturnino Gatti, was designed to embellish the high altar of a small sanctuary erected in commemoration of this event, which continues to exist to this day.

The painting illustrates a miraculous event that reportedly occurred on June 10, 1505, in San Polo Sabino, within the province of Rieti. According to historical sources, the weeping Virgin, attired in black akin to the tertiaries of the Order of Servants of Mary and seated on a walnut tree, appeared to a young girl. The Virgin revealed wounds inflicted by human sins and directed the girl to admonish the populace to engage in penance and adhere to the faith’s precepts. This artwork, possibly created within the circle of Saturnino Gatti, was designed to embellish the high altar of a small sanctuary erected in commemoration of this event, which continues to exist to this day.

Details of work

Catalog entry

The subject of the painting is related to the original location of the work in the sanctuary known as the Madonna della Noce, situated in the hamlet of San Polo Sabino, near Tarano, in the province of Rieti. Arcangelo Giani, in his annals of the Order of the Servite Friars of 1622, documents an event that took place in San Polo: on June 9, 1505, a young girl named Giovanna, daughter of Ludovico di Michele, while working the land, saw a man dressed in the black habit of the Servants of Mary, who was reciting a rosary and greeted her by saying: “Hail Mary.” The friar, referring to the potential damage that storms could cause to the next harvest, informed the young woman that God was displeased with the sins of the people and requested that she inform her fellow villagers to fast and do penance. Giovanna did not share this vision with anyone, as she remained skeptical. On June 10, while washing clothes, Giovanna heard a voice calling from a walnut tree. She looked up and saw an image of the Virgin Mary, dressed in black and crying, sitting among the branches. Mary asked why Giovanna had not relayed the message and revealed wounds on her chest and knees, instructing her to go immediately to the parish priest so he could ring the bell to gather the residents of San Polo. The priest was to preach that they should confess, fast, honor feast days, and hold processions for three days to appease God’s wrath and the sufferings of the Virgin. Following this event, the local inhabitants decided to build a small sanctuary dedicated to the Madonna della Noce (Giani, II, [1622] 1721, 23–24; Mortari 1957, 41–42, n. 26; Mortari 1960, 22–23, n. 12; Millesimi 1993, 78–79, n. 13; Sciarrini 2010, 44–65; BANLC, ms. cors. 37. D16. no. 2349, cc. 133–136).

The painting was created for a rural and peasant context, where religious faith was closely connected to the cycles of the seasons and agricultural work (see Seppilli 1989; Tozzi 1992; Ramelli 1997). The work, which accurately reproduces what is described in Giani’s annals, was painted for the high altar of the sanctuary established after the miracle and maintained by the Servite fathers until the suppression of the order and the disposal of their convent in San Polo in 1652 (Campanelli 2016, 267; BANLC, ms. cors. 37. D16. no. 2349, c. 29). The painting was in the small church on May 11, 1779, as mentioned during the pastoral visit of Cardinal Andrea Corsini (Savini Nicci 1935, 198; Pizzo 1994, 22; BANLC, ms. cors. 37. D16. no. 2349, cc. 13, 245–246). It has been suggested that it was later transferred to the convent of Santa Caterina in Rieti, due to the presence there in 1872 of a “Madonna delle Nocchie, work of the Perugian school” (Guardabassi 1872, 252; Millesimi 1993, 78–79, n. 13). However, this information probably refers to another work, as the Madonna della Noce is still mentioned on the main altar of the sanctuary in 1899 (Checchi 1899, 104; Sciarrini 2010, 50). Only later was it moved to the second altar on the left of the church of San Barnaba di San Polo, where it was recorded in 1932 (Palmegiani 1932, 525). The panel, intended for the Civic Museum of Rieti, was bought on the Roman antiques market on February 18, 1954. It was subsequently placed in storage at the Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia (Mortari 1957, 41–42 n. 26; Mortari 1960, 22–23 n. 12; Millesimi 1993, 78–79, n. 13).

The author of the painting has not been identified due to the challenge of distinguishing among various artists who were active in the L’Aquila and Latium areas in the early sixteenth century. The work has been associated with the circle of the Master of Capestrano, as well as with the Torresani, Jacopo Siculo, or Cola dell’Amatrice schools, with elements in the landscape that reflect the influence of Antoniazzo Romano (Lavagnino 1957, 3; Mortari 1957, 42; Mortari 1960, 23; Millesimi 1993, 78). The chromatic contrasts evident in the Virgin’s face are paralleled in the depiction of Saint Sebastian in the Pianella polyptych. This similarity in pictorial effects skillfully highlights the relief of the bodies. The polyptych in Pianella, now housed in the Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo, has been recently attributed to a collaboration between Sebastiano di Cola da Casentino and Bernardino di Cola di Merlo (Arbace 2011, 66–70, n. 9; Giancola 2020, 250–251). Previously, the work was solely ascribed to Bernardino di Cola di Merlo (Moretti 1968, p. 70, n. 278).

The plastic figure of the Virgin, characterized by her broad face streaked with tears and her half-open mouth revealing her teeth, may indicate a context where sculpture held equal importance to painting, such as the period associated with Saturnino Gatti (1463–1518), and Bernardino di Cola di Merlo. Some late works by Saturnino Gatti, including Saint Sebastian in the National Museum of Abruzzo (1517; Principi 2012, 111; Arbace 2019) and the Pietà in the Diocesan Museum of Ascoli Piceno (1517–1518; Principi 2012, 108; Maccherini 2018, 146–147, n. 21), could have inspired the poignant expressiveness and well-formed features of the Madonna in the Palazzo Venezia painting. Regarding the gestures and expressive power of the figures, comparisons can be drawn between the Virgin in this painting and Saint John in the Capture of Christ from the fresco cycle at San Panfilo in Villagrande di Torrimparte (1490–1494; Bologna 2014, 113, 128; Maccherini 2010, 124–125), or with the Virgin in the detached fresco in Santa Margherita in L’Aquila, whose date is disputed (Maccherini 2010, 126–127). The Virgin’s gestures also recall those of her praying counterpart sculpted by Gatti in collaboration with Giovanni Antonio di Giordano in 1499 (Principi 2012, 108). The refined landscape background of the piece is reminiscent of the panels depicting Our Lady of Sorrows and Saints in the Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo, attributed by Ferdinando Bologna to one of Gatti’s pupils, known by the pseudonym “Maestro del refettorio.” However, due to significant stylistic differences, this individual does not appear to be the author of the work in question (Bologna 2009, 208–209; Pezzuto 2010, 129–134).

Francesca Mari

State of conservation

Compromised. The surface of the artwork is significantly affected by extensive color loss impacting both the paint film and the preparation layer. This deterioration is attributed to the detachment and warping of the support boards, likely compounded by mechanical trauma or humidity in the lower section. On the right side, a sizable gap that resulted in the cutting or loss of a portion of the support was later repaired with a wooden panel. There is notable loss of lacquering, particularly on the leaves of the tree, and it is probable that this issue extends throughout the landscape.

Restorations and analyses

Before 1957, restoration efforts were conducted by B. Podio and M.T. Fasciani. Refer to Mortari (1957), page 41 for further details;

1981: restoration conducted by the Soprintendenza ai Beni Artistici e Storici di Roma; Millesimi 1993, 78;

from February 2005 to January 2006, restoration was conducted by Carlo Festa and Vincenzo Orrea, under the scientific supervision of Dr. Maria Selene Sconci;

2025: restoration was conducted by Susanna Sarmati, under the scientific supervision of Dr. Edith Gabrielli.

Provenance

Rome, Di Castro J., February 18, 1954, purchased for the Museo Civico di Rieti;

Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, storage, before 1957.

Sources and documents

Library of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana, Acta Sacrae Visitationis Castri S. Poli, ms. cors. 37. D16. n. 2349, cc. 13, 29, 133–136;

restoration report of 2006.

References

Giani Raffaello (Fra Giovanni Arcangelo), Annalium sacri ordinis Fratrum Servorum B. Mariae Virginis, II, Lucca [1622] 1721;

Guardabassi Mariano, Indice guida dei monumenti pagani e cristiani riguardanti l’istoria e l’arte esistenti nella provincia dell’Umbria, Perugia 1872;

Checchi Giuseppe Maria, I santuari della Vergine in Sabina, Rieti 1899, p. 104;

Palmegiani Francesco, Rieti e la regione sabina, Roma 1932, p. 525;

Savini Nicci Oliviero, Gli atti della S. visita del Cardinale Andrea Corsini (1779-1782), in «Latina gens», 8, 1935, pp. 193-206;

Lavagnino Emilio, Prefazione, in Mortari Luisa (a cura di), Opere d’arte in Sabina dall’XI al XVII secolo, catalogo della mostra (Rieti, Museo Civico, 1957), Roma 1957, p. 13;

Mortari, in Mortari Luisa (a cura di), Opere d’arte in Sabina dall’XI al XVII secolo, catalogo della mostra (Rieti, Museo Civico, 1957), Roma 1957, pp. 41-42, n. 26;

Mortari Luisa, Museo Civico di Rieti. Dal Medioevo al XX secolo, Roma 1960, pp. 22-23, n. 12;

Moretti Mario (a cura di), Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo nel castello cinquecentesco dell’Aquila, L’Aquila 1968;

Seppilli Tullio, Le Madonne arboree: note introduttive, in Giani Gallino Tilde (a cura di), Le Grandi Madri, Milano 1989, pp. 101-117;

Tozzi Ileana, Il culto delle Madonne arboree nelle Diocesi di Rieti e Sabina e aquilano, 1992, pp. 90-91;

Millesimi, in Leggio Tersilio, Marinelli Manuela, Millesimi Ines, Salvi Anna Paola, Museo Civico di Rieti, Rieti 1993, pp. 78-79, n. 13;

Leggio Tersilio, Marinelli Manuela, Millesimi Ines, Salvi Anna Paola, Museo Civico di Rieti, Rieti 1993;

Pizzo Marco, Le visite pastorali del cardinale Andrea Corsini nella Diocesi sabina (1779-1782), Rieti, Roma 1994, p. 22;

Ramelli Maria Enrica (a cura di), Le Madonne arboree, Milano 1997;

Tozzi Ileana, Il culto delle Madonne arboree nelle Diocesi di Rieti e Sabina, in «Silvae. Rivista tecnico scientifica del corpo forestale dello Stato», 7, 2007, pp. 234-260;

Bologna Ferdinando, Le arti nel monastero e nel territorio di Sant’Angelo d’Ocre, in Savastano Cosimo (a cura di), Sant’Angelo d’Ocre, Castelli 2009, pp. 183-209;

Maccherini Michele, Saturnino Gatti e la sua bottega, in Maccherini Michele (a cura di), L’arte aquilana, L’Aquila 2010, pp. 121-129;

Pezzuto Luca, Il Maestro del refettorio, in Maccherini Michele (a cura di), L’Arte Aquilana, L’Aquila 2010, pp. 129-134;

Sciarrini Gigliola, La Madonna della Noce. La sua Chiesa. Nella Fede, nella Storia, nell’Arte, Rieti 2010, pp. 44-65;

Arbace, in Arbace Lucia, Ferrara Daniele (a cura di), Rinascimento danzante. Michele Greco da Valona e gli artisti dell’Adriatico tra Abruzzo e Molise, catalogo della mostra (Celano, Castello Piccolomini 28 luglio-1 novembre 2011), Torino 2011, pp. 66-70, n. 9;

Principi Lorenzo, Il Sant’Egidio di Orte: aperture per Saturinino Gatti scultore, in «Nuovi Studi», 18, 2012, pp. 101-128;

Bologna Ferdinando, Saturnino Gatti. Pittore e scultore nel Rinascimento italiano, L’Aquila 2014;

Campanelli Marcella, Geografia conventuale in Italia nel XVII secolo. Soppressioni e reintegrazioni innocenziane, Roma 2016;

Maccherini, in Papetti Stefano, Pezzuto Luca (a cura di), Cola dell’Amatrice. Da Pinturicchio a Raffaello, catalogo della mostra (Ascoli Piceno, Musei Civici, 17 marzo-15 luglio 2018), Cinisello Balsamo 2018, pp. 146-147, n. 21;

Arbace Lucia (a cura di), San Sebastiano. La seduzione dell’arte e della poesia. Silvestro dell’Aquila Saturnino Gatti e Gabriele D’Annunzio, Pescara 2019;

Giancola, in Arbace Lucia (a cura di), MUNDA Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo. Storia. Testimonianze. Restauri, Ortona 2020, pp. 250-251.