Madonna and Child Enthroned with Two Angels

Master of the Piedigrotta Pietà ? 1460–1475

This intricate yet enigmatic panel features a Madonna and Child Enthroned, framed by an exquisite brocade cloth held aloft by two angels. The presence of elements from both Flanders-Iberian and Franco-Burgundian painting traditions suggests it may originate from Campania. It is possibly the work of an anonymous Master active in Naples during the latter half of the fifteenth century, renowned for his panel paintings, particularly the Pietà in the church of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta in Naples. This piece was inspired by Petrus Christus's Lamentation, currently housed in Brussels.

This intricate yet enigmatic panel features a Madonna and Child Enthroned, framed by an exquisite brocade cloth held aloft by two angels. The presence of elements from both Flanders-Iberian and Franco-Burgundian painting traditions suggests it may originate from Campania. It is possibly the work of an anonymous Master active in Naples during the latter half of the fifteenth century, renowned for his panel paintings, particularly the Pietà in the church of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta in Naples. This piece was inspired by Petrus Christus's Lamentation, currently housed in Brussels.

Details of work

Catalog entry

A hieratic Madonna, characterized by a pensive and melancholic expression, is portrayed seated on a plain wooden throne that lacks a backrest. The throne is embellished with wooden inlays that include perspective shelves integrated into the thickness of the seat. She is holding the infant Jesus on her lap. Her long blond hair cascades over her shoulders and is lightly covered by a delicate transparent veil that frames her face. Her visage is crowned by an intricately designed diadem adorned with faux cabochons, contrasting with the halo engraved with concentric circles on the outer edge and stripes on the inner area.

A cerulean mantle, lined with green fabric and bordered by luxurious embroidery featuring gold and pearl quatrefoils, partially conceals the rich damask fur robe, which lies in copious folds on a floor decorated with burgundy and black ceramic tiles and traditional Spanish azulejos. The Child’s face is framed by a cruciferous halo, with a fixed and resigned gaze foreshadowing the future Passion. This is further signified by the unusual choice of loincloth and the peculiar leg position. The two figures cast a shadow on the purple brocade with green borders that forms the background, supported at the upper edges by two angels and adorned with large peach-colored seven-lobed thistle leaves contrasting with pinecones in the central nucleus in mission gold.

The first mention of the painting, which entered Palazzo Venezia from the Collezione Sterbini where it was listed as a fifteenth-century Sardinian artwork, dates back to Santangelo (1947), who noted its quality and suggested a Valencian origin or execution by Valencian painters working in Italy. Generically attributed to the Spanish School by Zeri (1955), the painting was assigned by Sricchia Santoro (1986) to an Aragonese painter familiar with the style of Piero della Francesca. This painter is thought to have derived the solid volumetric forms of the figures and clear light from Piero’s work. The scholar proposed that this painter was the Master of the Pietà of Piedigrotta, a figure reconstructed by Causa (1953; Causa 1957; Causa 1960).

The artist, named after the work kept in the Neapolitan church of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta, is also the creator of the triptych of the “Scorziata” and of paintings depicting Saints Stephen, Sebastian, and George for the church of Santi Severino e Sossio in Naples. Bologna (1977) and Navarro (1987) identified him as the Toledan painter known as the “Luna Master,” initially identified by Post (1933, IV, 2). Sricchia Santoro (2017) later proposed the name Salvatore da Valenza for his Roman works, documenting the artist’s presence in Rome (1455, 1456, 1458) during the pontificate of Callixtus III and at the advent of Pius II (Müntz 1878, I, pp. 204–206, 330; Longhi [1926] 1967; Bologna 1977). However, this hypothesis remains unproven as no works are directly linked to this name.

The milky consistency of the veil and the pallor of the flesh, articulated by clear light and stereometric forms, like the oval of the Virgin, resemble the Provençal school, from Enguerrand Quarton to Josse Lieferinxe. Examples include the Retablo Requin and the Saint Catherine in the Musée du Petit Palais in Avignon (Labande 1932, I–II; Sterling 1983), which use large à ramages drapery as the background of the composition.

Simultaneously, the incorporation of relief plaster decorations and traditional azulejos flooring exhibit evident Spanish influences. Notable examples include San Baudilio in the parish church of Saint Boi de Llobregat by Luis Dalmau (Ruiz i Quesada, 2006) and the Crowning with Thorns by Joan Reixach housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Domenech, 2005; Domenech & Frechina, 2009). Specifically, the azulejos depicted in this painting evoke those seen in the renowned Delivery of the Franciscan Rule by Colantonio, a prominent artist who seamlessly integrated Flemish and Franco-Burgundian elements into his work in Naples during the mid-century, subsequently influencing Antonello da Messina.

The meticulous attention to detail in the fabrics, jewels, and reflections on the pearl-studded cape highlights an update influenced by Flemish trends, known in France since Barthelemy d’Eyck’s time and in Spain from the 1440s. An example is the triptych featuring the Madonna and Child, Queen Maria of Castile, Saint Michael, and Saint Jerome in the Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt (Company i Clement 2006).

Significant affinities can be found between this painting and others from the small corpus of the Master of Piedigrotta, which are characterized by a blend of Provençal tradition, Pierfrancescan culture, and Flemish-style attention to materials (see the doctoral studies of Orazio Lovino). The stereometric construction of the Virgin’s head is reminiscent of those in the Madonna of the Pietà and in the Scorziata triptych, where the identical solution of the carved drape at the bottom of the composition and the throne without a backrest is observed. Particularly noteworthy is the comparison between the Child and Saint Sebastian in the triptych housed in the church of Santi Severino e Sossio: the vacant gaze and subtle chiaroscuro transitions of their exposed torsos, barely suggesting delicate musculature, imply a temporal proximity between these works. Consequently, this panel in Palazzo Venezia can be dated to the third quarter of the fifteenth century, likely marking the beginning of the artist’s career.

Christ’s leg position is similar to the Madonna and Child by the Master of Nola (Paris, Sarti Gallery; Caramico 2017; Zappasodi 2017) and to the pose in an earlier depiction of a Child touching his left foot (Shorr 1954, type 35) found in a panel by Andrea de Aste in a private collection (De Marchi 1991). There is also a Madonna and Child in a private collection, considered a potential simplified copy of a work by Antonello (Longhi 1953; Sricchia Santoro 2017) that shares several characteristics with the Palazzo Venezia composition. This suggests that both compositions may originate from a design commonly found in southern Italy, featuring a checkered floor, a damask drape backdrop, and a distinctive wooden seat, which precedes the thrones seen in Antonello’s later period works, such as the polyptych of San Gregorio di Messina, 1473.

Our thanks go to Riccardo Naldi and Mauro Natale for their invaluable advice.

Mariaceleste Di Meo

Entry published on 27 March 2025

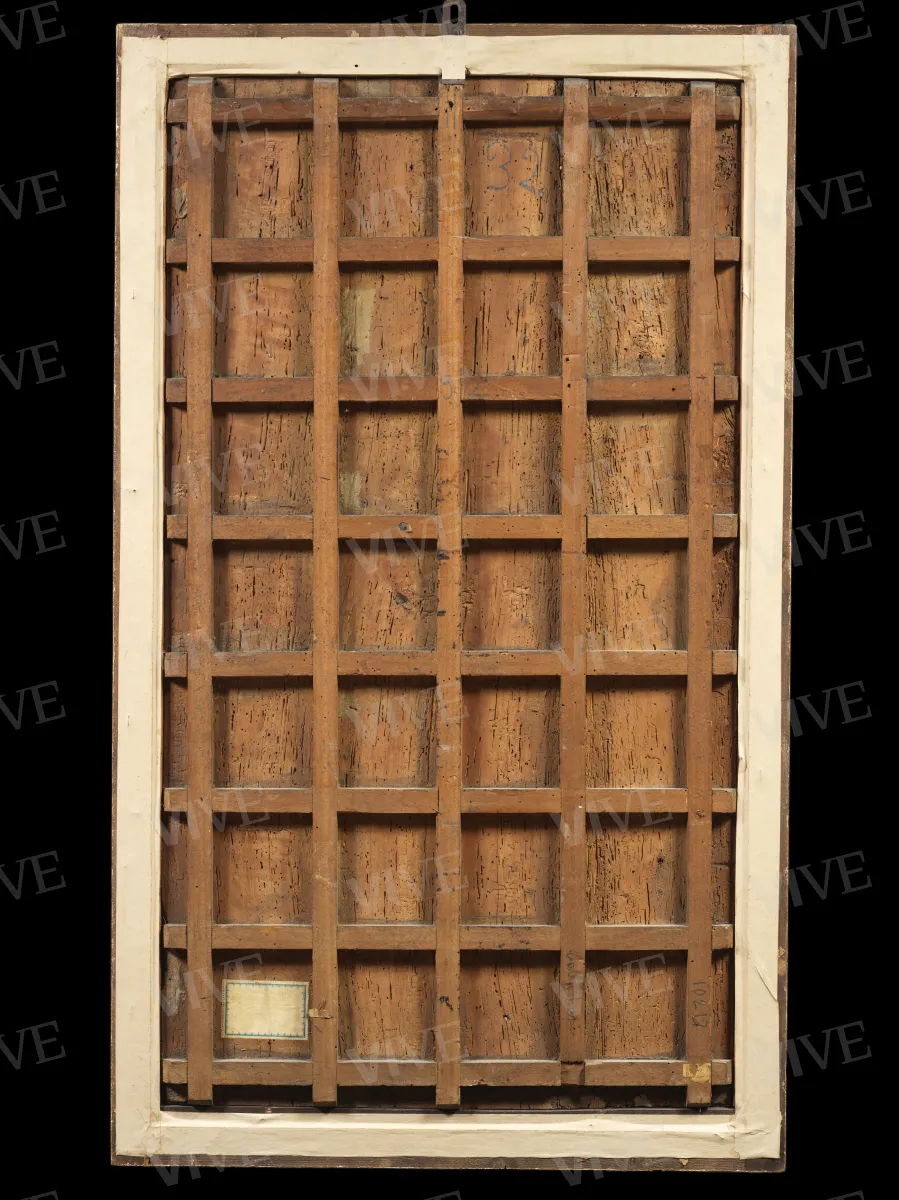

State of conservation

Fair.

Provenance

Rome, Collezione Giulio Sterbini;

Rome, Collezione Lupi;

Rome, gift of Giovanni Armenise, July 15, 1940;

Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, 1940.

References

Müntz Eugène, Les arts à la cour des papes pendant le XVe et le XVIe siècle, recueil de documents inédits tirés des archives et de bibliothéques romaines, I, Martin V-Pie II, Paris 1878, pp. 204-206, 330;

Labande Léon-Honoré, Les primitifs français, I-II, Marseille 1932;

Post Chandler Rathfon, A History of Spanish Painting, IV, 2, The Hispano-Flemish Style in North-Western Spain, Cambridge/Mass. 1933, pp. 371-380;

Santangelo Antonino (a cura di), Museo di Palazzo Venezia. Catalogo. 1. Dipinti, Roma 1947, pp. 3-44;

Longhi Roberto, Frammento siciliano, in «Paragone. Arte», 4, 1953, 47, pp. 3-44;

Causa, in Molajoli Bruno (a cura di), III Mostra di restauri, catalogo della mostra (Napoli, Museo di San Martino, 20 dicembre 1953-20 marzo 1954), Napoli 1953, pp. 8-9, n. 4, fig. 9;

Shorr Dorothy C., The Christ Child in Devotional Images in Italy During the XIV Century, New York 1954;

Zeri Federico (a cura di), Catalogo del Gabinetto Fotografico Nazionale. 3. I dipinti del museo di Palazzo Venezia in Roma, Roma 1955, p. 10, n. 145;

Causa Raffaello, Pittura napoletana dal XV al XIX secolo, Bergamo 1957;

Causa Raffaello, in IV Mostra di restauri, catalogo della mostra (Napoli, Palazzo Reale, 13 novembre-11 dicembre 1960), Napoli 1960, pp. 49-50, catt. 10-11;

Longhi Roberto, Primizie di Lorenzo da Viterbo (1926), in Edizione delle opere complete di Roberto Longhi, II, 1, Saggi e ricerche 1925-1928, Firenze 1967, pp. 53-61;

Bologna Ferdinando, Napoli e le rotte mediterranee della pittura: da Alfonso il Magnanimo a Ferdinando il Cattolico, Napoli 1977, pp. 83, 91-94;

Sterling Charles, Enguerrand Quarton: le peintre de la Pietà d’Avignon, Paris 1983;

Sricchia Santoro Fiorella, Antonello e l’Europa, Milano 1986, pp. 67-68, 79, nota 13, fig. 49;

Navarro Fausta, Maestro della Pietà di Piedigrotta, in Zeri Federico (a cura di), La Pittura in Italia. Il Quattrocento, II, Milano 1987, p. 679;

De Marchi Andrea, Andrea de Aste e la pittura tra Genova e Napoli all’inizio del Quattrocento, in «Bollettino d’arte», 76, 1991, 68/69, pp. 113-130;

Domenech Fernando Benito (a cura di), La memoria recobrada: pintura valenciana recuperada de los siglos XIV-XVI, catalogo della mostra (Valencia, Museo de Bellas Artes, 27 ottobre 2005-8 gennaio 2006; Salamanca, Sala de exposiciones Caja Duero, 9 febbraio-19 marzo 2006), Valencia 2005;

Company i Clement Ximo, La edad dorada de la pintura valenciana (s. XV), in Belenguer Ernest, Garín Felipe (a cura di), La corona de Aragón: siglo XII-XVIII, Madrid 2006, pp. 403- 453;

Ruiz i Quesada Francesc, Lluís Dalmau, in L’art gòtic a Catalunya, VI, Darreres manifestacions, Barcelona 2006, pp. 56-59;

Domenech Fernando Benito, Frechina José Gómez (a cura di), La edad de oro del arte valenciano, remomeración de un centenario, catalogo della mostra (Valencia, Museo de Bellas Artes, 1 febbraio-27 aprile 2009), Valencia 2009;

Caramico Virginia, La pittura a Napoli e in Campania al tempo di Ladislao e Giovanna Durazzo, in Zappasodi Emanuele (a cura di), Il Maestro di Nola, un vertice impareggiabile del tardogotico a Napoli e in Campania, Firenze 2017, pp. 47-63;

Sricchia Santoro Fiorella, Antonello, i suoi mondi, il suo seguito, Firenze 2017, pp. 103, 129, fig. 36, 142, nota 5, fig. 4;

Zappasodi Emanuele, La “Madonna del latte”, un capolavoro del Maestro di Nola, in Zappasodi Emanuele (a cura di), Il Maestro di Nola, un vertice impareggiabile del tardogotico a Napoli e in Campania, Firenze 2017, pp. 9-45.