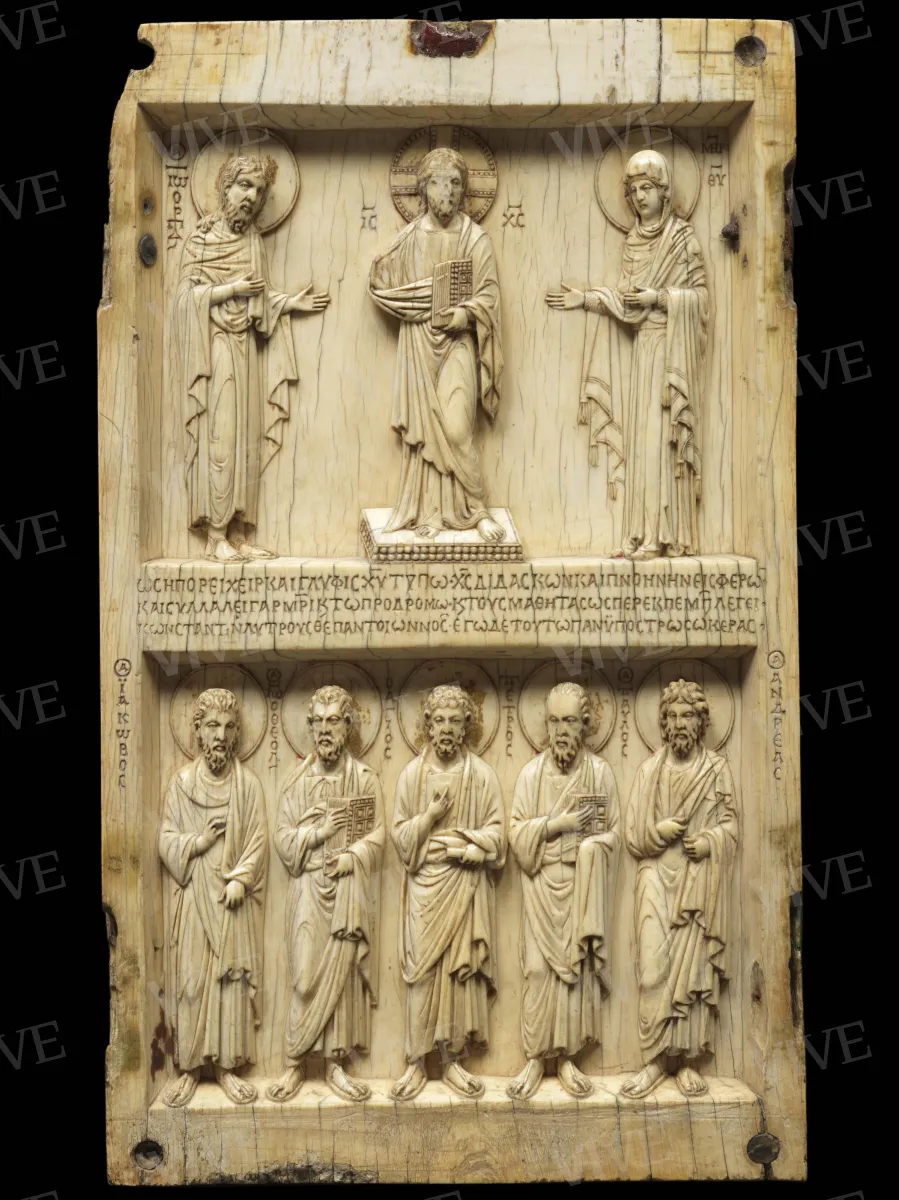

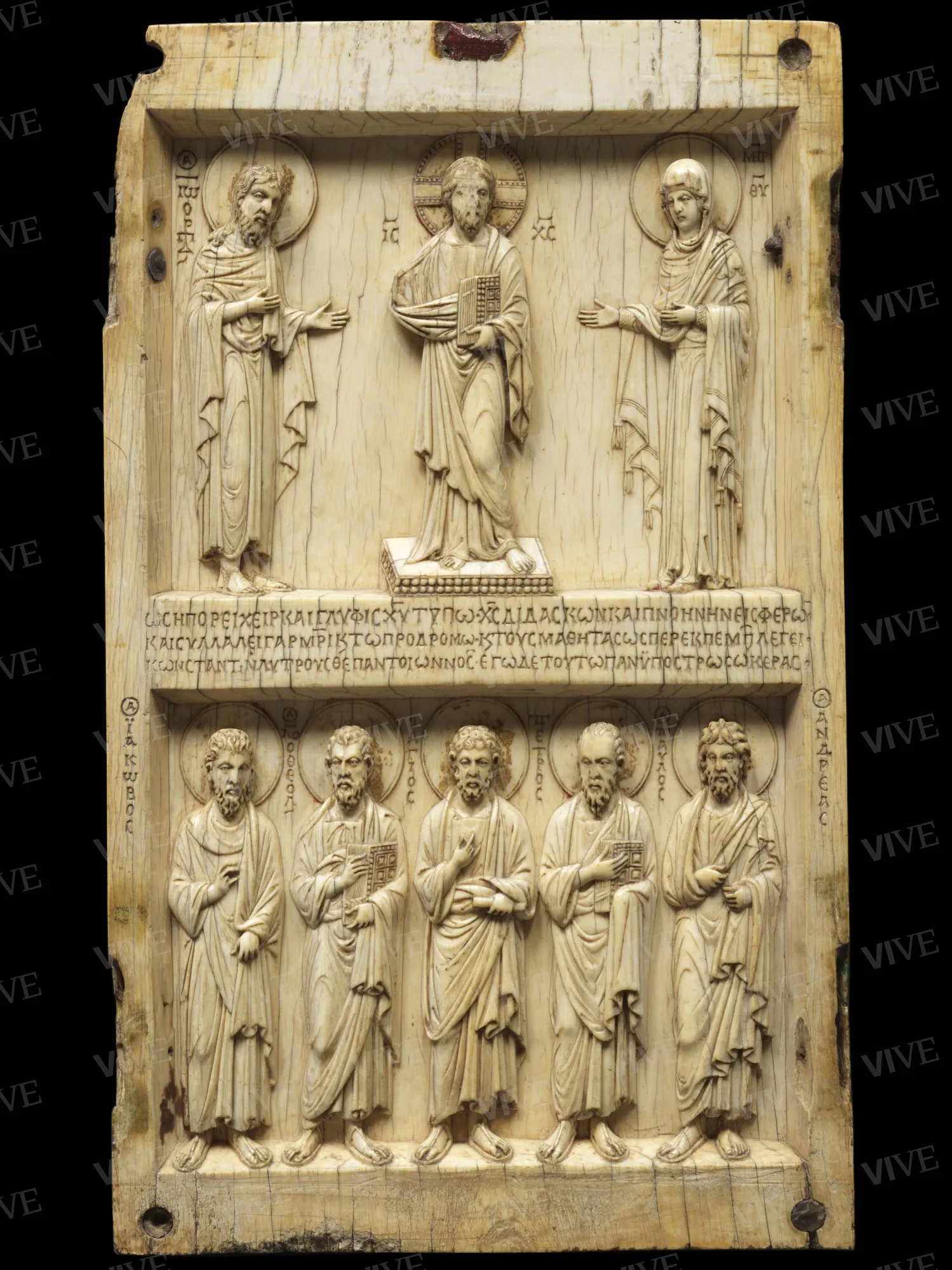

Ivory triptych with Deesis (Christ in Majesty) and saints

Byzantine production Mid-10th century

Carved on the ivory triptych are the Deesis (an iconographic representation of Byzantine origin depicting Christ flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist in the act of praying for sinners) and numerous saints. The ivory, which retains traces of color and gilding, is embellished with engraved inscriptions in Greek. The work, which is extremely elegant in terms of composition and style, was probably produced in Constantinople around the mid-tenth century for the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913–959).

Carved on the ivory triptych are the Deesis (an iconographic representation of Byzantine origin depicting Christ flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist in the act of praying for sinners) and numerous saints. The ivory, which retains traces of color and gilding, is embellished with engraved inscriptions in Greek. The work, which is extremely elegant in terms of composition and style, was probably produced in Constantinople around the mid-tenth century for the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913–959).

Details of work

Catalog entry

The ivory triptych is an elegant specimen produced in the mid-tenth century in Constantinople. The interior part of the central panel is divided into two registers by a long inscription in Greek. In the upper register is a depiction of the Deesis, an iconographic representation of Byzantine origin depicting Christ flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist in the act of praying for sinners. This iconographic staple, however, is given a curious twist: John the Baptist, and not the Virgin, is shown to the right of Christ. This anomaly is probably due to the fact that the male figure was an ideal representation of the patron, and was therefore given a more prominent position within the work (Kalavrezou 1997). The lower register depicts James, John, Peter, Paul, and Andrew, perhaps alluding to the main bishoprics of Jerusalem, Ephesus, Rome, and Constantinople (Weitzmann 2000, 19). On the back of the central panel is a large carved cross with a rosette in the center and at the termination of each arm. On the side panels are depicted saints in a standing position, two in each of the upper and lower registers, which are also separated by Greek inscriptions. The saints differ in their robes and attributes: the warriors and martyrs wear a chlamys (that is, a cloak), and bear a sword or cross; the bishops wear a paenula or phelonion (a round vestement with a hole for the head), an omophorion (a stole decorated with crosses and worn over the shoulders) and are depicted holding a book. All are depicted in full-length while standing and with haloes (Christ’s halo is crocesignata, or bearing a cross) and are identifiable by their accompanying engraved Greek names. The central panel inscription, which is deftly designed to fit the space available, invokes divine protection for a certain Constantine. More recent scholarship has identified this Constantine with Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913–959), the recipient and perhaps also the commissioner of the work, and it has been speculated that the prayers also served to restore the basileus’ state of health, which would date the work to the last years of his reign (Oikonomides 1995, 76–77) when, according to reliable sources, he was unwell. The inscriptions on the side doors extol the saints as defenders of the faith and divine intermediaries, and the intercessory function expands from the Deesis triad to all the figures carved in the ivory. The work has also been interpreted as representing the ideology of imperial military victory achieved thanks to support from religion (Oikonomides 1995; Pentcheva 2010; Nelson 2011–2012. There has also been a recent trend to read this as a depiction of Christ’s court in the Final Judgment and a visual paradigm for the structure of the court of the basileus (Eastmond 2015). Whatever the reading, there is no doubt that the work’s force relies on two fundamental elements: the image and the written word.

The presence of several little-known saints placed in a highly visible position once the wings of the triptych are closed has been explained as a sign of the patron’s own individual devotion, going so far as to speculate the work’s provenance from a specific church in the capital of the empire dedicated specifically to those saints—the martyrs Severianus and Agathonicus—or at least to one of them (Oikonomides 1995, 71, 77), a hypothesis that not all scholars accept, citing the fact that these saints are not visible when the triptych is open (Eastmond 2015, 83–84). The inclusion of Arethas, another factually somewhat extraneous saint, has been justified due to Constantine VII’s special interest in the saint (White 2013, 79). There is some speculation regarding the differences in the characters’ haloes: is the fact that only the haloes of Saint Theodore Tyrone and perhaps Saint Eustace, which are in the upper register of the left panel when the triptych is open, are framed with a pattern of small oval and lined decorations, an indication of the importance to be accorded these saints? Were they signaling the beginning of the reading? What is certain is that the Church Fathers are entrusted with the first line of defense; in fact, they appear on the doors when the triptych is closed, while the military saints are inside, closer to Christ, reversing the “setting” we find in monumental decorations (Eastmond 2013; Eastmond 2015, 75).

The object could have had an imperial or liturgical ritual or votive function; it has also been suggested that it could be used while traveling on occasions when it might be complicated or impossible to attend a church (Eastmond 2013).

Traces of gilding (particularly on the central panel) and color are visible on the ivory, but it is not possible to determine whether they were there originally.

The work depicts voluminous figures, an absence of anatomical deformations, small variations in poses, classical drapery, measure, balance and elegance, and is perfectly in keeping with the period defined by critical literature as the “Macedonian renaissance.”

The object’s iconographic scheme is comparable to two other ivory triptychs now in the Vatican Museums and the Louvre and dated between the tenth and eleventh centuries. These triptychs have more characters, the presence of angels, a greater richness of detail, and the figure of Christ enthroned. The Palazzo Venezia work, because of its compositional simplicity and the presence of the inscriptions that imply an ad hoc production, has been posited by some scholars as the first exemplar, from which the other two must have derived, but it is probably wrong to interpret these works in terms of originals and copies (Eastmond 2015).

The triptych dedicated to Constantine has been documented in Rome since at least 1600 (Moretti 2012).

Simona Moretti

Entry published on 12 February 2025

State of conservation

Breaks and cavities along edges; face of Christ is abraded; hinges are lost.

Inscriptions

Closed triptych, left panel, central inscription:

“MAPTΥC CΥNAΦΘEIC EN TPI-

THERE ΘΥHΠOΛOIC : ΠICTOIC TO TPIT-.

TON EΥMENIZETAI CEBAC :”;

closed triptych, left panel, upper register inscription:

“A[ΓIOC]B[ACI]ΛEIOC.”;

closed triptych, left panel, lower register inscription:

“A[ΓIOC] ΓPHΓOP[IOC] OR ΘAΥMAT[ΟΥPΓOC].”

closed triptych, right panel, central inscription:

“APXIEPEIC TPEIC EIC MECITEIAN.

MIAN : KAI MARTΥC ECTI ΓHN

ΥΠOKLINEIN CTEΦEI :”;

closed triptych, right panel, upper register inscriptions:

“A[ΓIOC] ΓPHΓOP[IOC] OR ΘEOΛOΓOC.

A[ΓIOC] IΩANNHC OR XPΥCOCT[OMOC]

A[ΓIOC] KΛHMHC AΓKΥPAC.”;

Closed triptych, right panel, lower register inscriptions:

“A[ΓIOC] CEΥHPIANOC

A[ΓIOC] AΓAΘONIKOC

A[ΓIOC] NIKOΛAOC.”;

open triptych, central panel, central inscription:

ΩC HΠOPEI XEIP KAI ΓΛΥΦIC X[PICTO]Υ TΥΠΩ - X[PICTO]C ΔIΔACKΩN KAI ΠNOHN HN EICΦEPΩ[N] -

KAI CΥΛΛAΛEI ΓAP M[HT]PI K[AI] TΩ ΠPOΔPOMΩ - K[AI] TOΥC MAΘHTAC ΩCΠEP EKΠEMΠ[ΩN] ΛEΓEI -

KΩNCTANTIN[ON] ΛΥTPOΥCΘE ΠANTOIΩN NOC[ΩN] - EΓΩΔE TOΥTΩΠAN ΫΠOCTPΩCΩ KEPAC -”;

open triptych, central panel, upper register:

A[ΓIOC] IΩ[ANNHC] O ΠP[O]Δ[POMOC] I[HCOΥ]C X[PICTO]C M[HT]HP Θ[EO]Υ;

open triptych, central panel, lower register:

“A[ΓIOC] ÏAKΩBOC A[ΓIOC] IΩ[ANNHC] O ΘEOΛ[OΓOC] O AΓIOC ΠETPOC A[ΓIOC] ΠAΥLOC A[ΓIOC] ANΔPEAC.”;

open triptych, left panel, central inscription:

“ANAΞ O TEΥΞAC MAPTΥPΩN.

THN TETPAΔA : TOΥTOIC TPO-

ΠOΥTAI ΔΥCMENEIC KATA KPAT[OC] :”;

open triptych, left panel, upper register inscriptions:

“A[ΓIOC] ΘEOΔΩP[OC] OR THPΩN

A[ΓIOC] [...]C.”;

open triptych, left panel, lower register inscriptions:

“A[ΓIOC]ΠPOKOΠIOC

A[ΓIOC] APΕΘAC.”;

open triptych, right panel, central inscription:

“IΔOΥ ΠAPECTIN H TETPAKTΥC.

MARTΥPΩN : TΩN APETΩN KO-

CMOΥCA TETPAΔI CTEΦOC :”;

open triptych, right panel, upper register inscriptions:

“[AΓIOC ΘEOΔΩPOC OR CTP]ATHLAT[ΗC]

A[ΓIOC] ΓEΩPΓIOC.”;

open triptych, right panel, lower register inscriptions:

“A[ΓIOC]ΔHMHTPHOC

A[ΓIOC] EΥCTPATIOC.”

Provenance

Rome, Fulvio Orsini collection (documented in 1600);

Rome, basilica of Saint John Lateran (first quarter of the seventeenth century);

Rome, Collezione Barberini (documented from 1628);

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense (from 1748);

Rome, Museo di Castel Sant’Angelo (arrived in 1914);

Rome, Museo di Palazzo Venezia (documented since 1920).

Exhibition history

Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Palais du Louvre, Pavillon de Marsan, Exposition Internationale d’art byzantin, May 28–July 9, 1931, no. 96;

Ravenna, Chiostri Francescani, Catalogo della mostra degli avori dell’Alto Medioevo, September 9–October 21, 1956, no. 103;

Edinburgh, Royal Scottish Museum; London, Victoria and Albert Museum, Masterpieces of Byzantine Art, August 23–13 September, and October 1–November 9 1958, no. 68;

Athens, Zappeion Exhibition Hall, Byzantine Art, a European Art, April 1–June 15, 1964, no. 69;

Venice, Palazzo Ducale, Venezia e Bisanzio, June 8–September 30 1974, no. 22;

Rome, Palazzo Venezia, Imago Mariae. Tesori d’arte della civiltà cristiana, June 20–October 2 1988, no. 11;

Ravenna, Museo Nazionale, Deomene. L’immagine dell’orante fra Oriente e Occidente, March 25–June 24, 2001, no. 124, fig. 124;

Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, Sala Altoviti, Cipro e l’Italia al tempo di Bisanzio. L’Icona Grande di San Nicola tis Stegis del XIII secolo restaurata a Roma, June 23–July 26 2009, no. 2.

Sources and documents

Los Angeles, UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections, Manuscripts Division, Orsini wills 16, bx. 240-241, fasc. 42, Jan. 21, 1600 [will of Fulvio Orsini];

Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, H 2 inf., f. 116r [copy of the inventory of Fulvio Orsini’s collection];

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Arch. Barb., Arm. 155, Inventario della Guardarobba, 1626-1631, f. 90v [inventory of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, 1628];

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Barb. lat. 5635, Inventario della Guardarobba, 1631-1636, f. 61r [inventory of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, 1631];

Rome, Biblioteca Casanatense, Ms. Cas. 433, Libro autentico dell’Introito ed Esito della Eredità Casanatense comincia dal dì. 8. Gennaro 1748, f. 6r [register of accessions: documentation of the sale of the triptych by Giovanni Antonio Costanzi to the Biblioteca Casanatense];

Rome, Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione, Direzione Generale, AA.BB.AA., Div. I 1908–1924, b. 213, fasc. 1033 [documentation on the transfer of the ivory triptych from the Biblioteca Casanatense to the Museum of Castel Sant’Angelo].

References

Hermanin Federico, Il Palazzo di Venezia. Museo e grandi sale, Bologna 1925, p. 71, tav. s.n.;

Goldschmidt Adolph, Weitzmann Kurt, Die byzantinischen Elfenbeinskulpturen des X.-XIII. Jahrhunderts, II, Berlin 1934 (rist. Berlin 1979), p. 33, n. 31, tavv. X e LXIII;

Kantorowicz Ernst, Ivories and Litanies, in «Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes», 5, 1942, pp. 56-81 (pp. 70-76);

Hermanin Federico, Il Palazzo di Venezia, Roma 1948, p. 292, figg. alle pp. 292-293;

Walter Christopher, Two Notes on the Deësis, in «Revue des Études Byzantines», 26, 1968, pp. 311-336 (p. 314 e fig. 2; rist. in Id., Studies in Byzantine Iconography, London 1977, pp. 311-336);

Cutler Anthony, The Hand of the Master: Craftmanship, Ivory, and Society in Byzantium (9th-11th centuries), Princeton 1994, pp. 157-158, 208 e ss., fig. 176;

Cutler Anthony, From Loot to Scholarship: Changing Modes in the Italian Response to Byzantine Artifact ca. 1200-1750, in «Dumbarton Oaks Papers», 49, 1995, pp. 237-268 (p. 255, nt. 122 alle pp. 255-256);

Oikonomides Nicholas, The Concept of “Holy War” and Two Tenth-century Byzantine Ivories, in Miller Timothy S., Nesbitt John (a cura di), Peace and War in Byzantium, Essays in Honor of George T. Dennis, S.J., Washington, D.C., 1995, pp. 61-86 (pp. 69-77);

Guillou André, Recueil des inscriptions grecques médiévales d’Italie, Rome 1996, pp. 51-53, , n. 50, tavv. 30-32;

Kalavrezou Ioli, Helping Hands for the Empire: Imperial Ceremonies and the Cult of Relics at the Byzantine Court, in Maguire Henry (a cura di), Byzantine Court Culture from 829 to 1204, Washington 1997, pp. 53-79 (pp. 75-76);

Weitzmann Kurt, Le icone di Costantinopoli, in Le icone (1981), Milano 2000 (ed. riveduta e aggiornata), pp. 14-81 (p. 19, fig. alle pp. 24-25);

Durand Jannic, Durand Maximilien, À propos du triptyque «Harbaville»: quelques remarques d’iconographie médio-byzantine, in Durand Maximilien (a cura di), Patrimoine des Balkans. Voskopojë sans frontières 2004, Paris 2005, pp. 133-155, 181, tavv. XXIII-XXVIII (pp. 136-137 et passim);

Pittiglio Gianni, Trittico Casanatense, in Barberini Maria Giulia, Sconci Maria Selene (a cura di), Guida al Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia, con prefazione di Strinati Claudio, Roma 2009, p. 55, n. 50;

Flamine Marco, Gli avori del «gruppo di Romano». Aspetti e problemi, in «Acme», 63, 2010, 2, pp. 121-152 (pp. 123, 136, 144-145);

Pentcheva Bissera V., Icone e potere. La Madre di Dio a Bisanzio (2006), Milano 2010, pp. 110-112;

Pentcheva Bissera V., The Sensual Icon. Space, Ritual and the Senses in Byzantium, University Park, PA, 2010a, pp. 179-180;

Rhoby Andreas, Byzantinische Epigramme auf Ikonen und Objekten der Kleinkunst, Wien 2010 (Byzantinische Epigramme in inschriftlicher Überlieferung, 2), Nr. E126-130, pp. 337-342, figg. 100-102 alle pp. 527-528;

Nelson Robert S., “And So, With the Help of God”. The Byzantine Art of War in the Tenth Century, in «Dumbarton Oaks Papers», 65-66, 2011-2012 (2012), pp. 169-192 (pp. 186-188, fig. 15);

Moretti Simona, Viaggio di un trittico eburneo da Costantinopoli a Roma. Note in margine al "Corpus degli oggetti bizantini in Italia", in Acconcia Longo Augusta, Cavallo Guglielmo, Guiglia Alessandra, Iacobini Antonio (a cura di), La Sapienza bizantina. Un secolo di ricerche sulla civiltà di Bisanzio all’Università di Roma, Atti della Giornata di studi (Roma, Sapienza Università di Roma, 10 ottobre 2008), Roma 2012, pp. 225-244;

Eastmond Antony, The Glory of Byzantium and Early Christendom, London 2013, pp. 142-143, n. 139;

White Monica, Military Saints in Byzantium and Rus, 900-1200, Cambridge 2013, pp. 78-80;

Moretti Simona, Roma bizantina. Opere d’arte dall’impero di Costantinopoli nelle collezioni romane, Roma 2014, pp. 58, 66-70, 79, 226-232 (n. 16), 270-273 et passim, figg. 14a/b-17a/b, 27, 94a/b;

Eastmond Antony, The Heavenly Court, Courtly Ceremony, and the Great Byzantine Ivory Triptychs of the Tenth Century, in «Dumbarton Oaks Papers», 69, 2015, pp. 71-114.