Double-faced pluteus with entwined circles

Roman milieu First half of 9th century

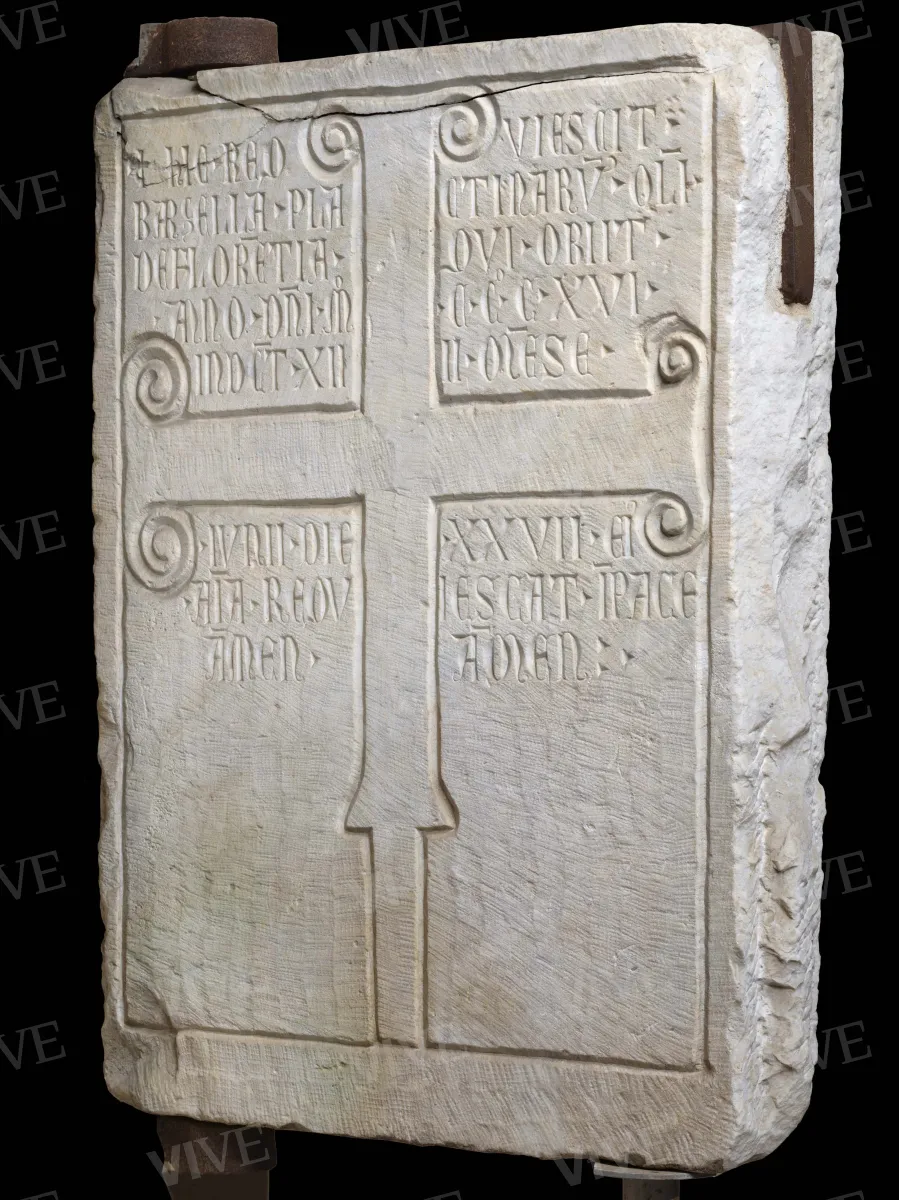

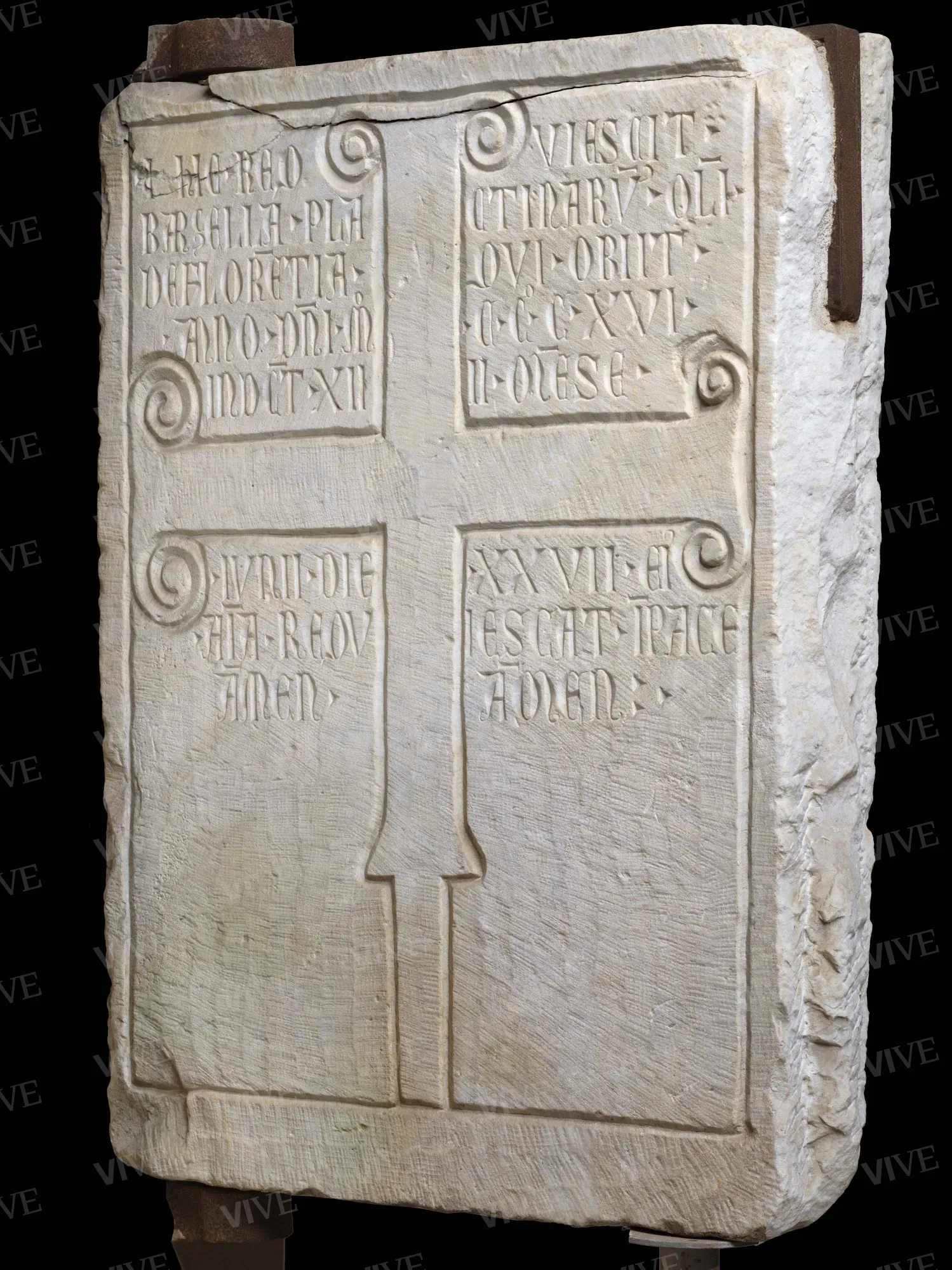

Double-faced marble pluteus slab, decorated on recto with a mesh of two-lined wickerwork motif ribbons, composed of three entwined circles intersected by diagonals, arranged in three registers and symmetrically flanked by semicircles with pointed oval eyelets, within a saw-tooth border. On the verso, an engraved astylar cross with scrolled extremities and bordered by a rectangular frame is surrounded in the upper half by a sepulchral epigraph in Gothic letters.

Double-faced marble pluteus slab, decorated on recto with a mesh of two-lined wickerwork motif ribbons, composed of three entwined circles intersected by diagonals, arranged in three registers and symmetrically flanked by semicircles with pointed oval eyelets, within a saw-tooth border. On the verso, an engraved astylar cross with scrolled extremities and bordered by a rectangular frame is surrounded in the upper half by a sepulchral epigraph in Gothic letters.

Details of work

Catalog entry

The recto of the marble slab with decorations on either face presents, within a saw-tooth border, an ornamental arrangement in three registers, consisting of three circles of entwined two-lined wickerwork motif ribbons intersected by diagonals, symmetrically flanked by semicircles with pointed oval eyelets. On the verso, an engraved astylar cross, positioned tangentially to an engraved frame, is surrounded for three-quarters of its entirety by a sepulchral epigraph in Gothic letters dated to the fourteenth century.

The recto shows slight irregularities in its decorative motifs, such as, for example, the rounding of the tip of the lozenge in the upper right margin and the uncertainty of interweaving ribbons in the lower half of the plate. The geometric pattern of the weave is, however, generally accurate, and the mesh allows large sections of the lowered surface of the ground plane to emerge with light and airy effects in harmonious chiaroscuro contrast with the interlaced ornamentation.

The pattern of intertwined circles crossed by diagonals, which has its roots in the late Roman decorative repertoire (close analogies can be seen in the Syrian lithostrata reported in Casartelli Novelli 2019, fig. 61c), can be dated to the extremely early medieval sculptural repertoire of central–northern Italy, with occurrences that, if we limit ourselves to the Roman area, date from the last quarter of the eighth century up to the middle of the ninth century: from Santa Pudenziana (Pani Ermini 1974, fig. 98) to San Giovanni a Porta Latina (Melucco Vaccato 1974, fig. 35a), from Santa Maria in Trastevere (Bull-Simonsen Einaudi 2001, fig. 8) to San Leone a Leprignano (Raspi Serra 1974, fig. 210).

Moreover, the saw-tooth border, combined with the use of the three-lined wickerwork motif ribbon, shifts the date to at least the first quarter of the ninth century, as this is characteristic of the production of the worksites linked to the patronage of Leo III (795–816) and Paschal I (817–824) (Melucco Vaccaro 1999; Roperti 2007; Ballardini 2008).

As for its intended use, the side edge visible today has a mortise recess for housing within an articulated piece of furniture, whether it was a pergula, an ambon, or even a cathedra. A presbytery enclosure is hypothesized by the architect who worked on the Austrian embassy Camillo Pistrucci, who, in his report for the 1910–1914 relocation of the Palazzetto Venezia, identified the slab as one of the plutei of the schola cantorum of the church of San Marco on the basis of its discovery in the cemetery of the diaconia and its reuse in a late medieval terragna, or slab, tomb. If the attribution to the San Marco schola cantorum is correct, the pluteus would have to be assigned to the second quarter of the ninth century and considered commissioned by Gregory IV (827–844), to whom we owe the third reconstruction of the church and its presbytery fittings (Krautheimer, Corbett, Frazer 1977; Cecchelli 1995).

If the similarity with the other slabs (inventory number 13608a/b/c, 13165, 3289, 13168, 3288) that Pistrucci considered made up a homogeneous group of fragments is doubtful (it is based only on a comparison of ornamental forms), the relationship that links our find to the pluteus with astylar cross between palmettes and interwoven circles (inv. 3291) is justified first of all because of the slab’s size (98x79, 2x14.1 cm) and the type of material used (Carrara marble). It is not too difficult to imagine that the two plutei are in keeping with the same liturgical fixtures, most likely a presbytery enclosure, also considering the almost one meter height, which is the same as that of similar artifacts of the Carolingian context in Italy’s center-north (Roth-Rubi 2018). Pistrucci provides us with an additional element when he reports that the verso of the twin pluteus, no longer extant, was decorated with “a magnificent ribbon ornament.” We do not know what lies behind the pluteus with palmettes, but if we assume an “interlaced ribbon” similar to our own, we might assess the astylar cross engraved in the verso of our pluteus as unfinished, that is, probably worked earlier than that of the twin pluteus. If so, Pistrucci would be correct in considering the two plutei as connected and similarly salvaged as late medieval shaft tomb covers, as the epigraph on our pluteus (“remembering the virtues of a young girl”) would indicate. The Gothically styled epigraph conforms to the space offered by the four free quadrants with “little accuracy” (Latini 2008) and mentions the deceased, a Florentine woman named Bargella, who died June 27, 1316.

Valentina Brancone

State of conservation

Good. Chipped in several places along the edge, with cracks at the top of the slab.

Restorations and analyses

1999 (cleaning)

Inscriptions

epigraph engraved on the verso of the slab: “† HIC REQUIESCIT / BARGELLA PLACTINARU(M) OLI(M) / DE FLORE(N)TIA QUI OBIIT / ANNO D(OMI)NI MCCCXVI / IND(I)CT(IONE) XIIII ME(N)SE / IUNII DIE XXVII EI(US) / A(N)I(M)A REQUIESCAT I(N) PACE / AMEN AMEN.”

Provenance

Unknown, possibly from the old diaconia of San Marco. Found during excavation work on the Palazzetto, as part of the demolition carried out for the relocation of the Palazzetto Venezia (1910–1914).

Sources and documents

Rome, Archivio del Museo del Palazzo di Venezia, Memorie dell’architetto Camillo Pistrucci. Demolizione e ricostruzione del Giardino di San Marco o Palazzetto di Venezia, ed edifici annessi, restauro del grande palazzo, torre, loggia papale della chiesa di San Marco e scoperte avvenute (1910–1914), page 51 and note 10;

Rome, Archivio del Museo del Palazzo di Venezia, Bollettario, IV tomo (handwritten annotation by Federico Hermanin, June 30, 1921).

References

Kautzsch Rudolf, Die römische Schmuckkunst in Stein vom 6. bis zum 10 Jahrhundert, in «Römisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte», III, 1939, pp. 3-73;

Melucco Vaccaro Alessandra, La Diocesi di Roma, t. III, La II regione ecclesiastica, Corpus della scultura altomedievale, VII, Spoleto 1974;

Pani Ermini Letizia, La Diocesi di Roma, t. I, La IV regione ecclesiastica, Corpus della scultura altomedievale, VII, Spoleto 1974;

Raspi Serra Joselita, La Diocesi dell’Alto Lazio. Bagnoregio, Bomarzo, Castro, Civita Castellana, Nepi, Orte, Sutri, Tuscania, Corpus della scultura altomedievale VIII, Spoleto 1974;

Macchiarella Gianclaudio, Note sulla scultura in marmo a Roma tra VIII e IX secolo, in Istituto di Storia dell’Arte dell’Università di Roma (a cura di), Roma e l’età carolingia. Atti delle giornate di studio (Roma, 3-8 maggio 1976), Roma 1976, pp. 289-299;

Krautheimer Richard, Corbett Spencer, Fraze Alfred, Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae. The Early Christian Basilicas of Rome (IV-IX Cent.), Città del Vaticano 1977;

Cecchelli Margherita, La Basilica di San Marco a Piazza Venezia (Roma). Nuove scoperte e indagini, in Akten des XII. Internationalen Kongresses für Christliche Archäologie (Bonn, 22-28 settembre 1992), 2, Münster 1995, pp. 640-644;

Melucco Vaccaro Alessandra, Le officine marmorarie romane nei secoli VII-IX. Tradizione e apporti, in Cadei Antonio et al. (a cura di), Arte d’Occidente. Temi e metodi. Studi in onore di Angiola Maria Romanini, I, Roma 1999, pp. 299-308;

Paroli Lidia, La scultura a Roma tra il VI e il IX secolo, in Arena Maria Stella, Delogu Paolo, Paroli Linda et al. (a cura di), Roma dall’Antichità al Medioevo. Archeologia e storia nel Museo Romano Crypta Balbi, Vol. I, Milano 2001, pp. 132-143, 487-493;

Bull-Simonsen Einaudi Karin, L’arredo liturgico medievale in Santa Maria in Trastevere, in de Blaauw Sible (a cura di), Arredi di culto e disposizioni liturgiche a Roma da Costantino a Sisto IV. Atti del Colloquio internazionale (Roma, 3-4 dicembre 1999), Roma 2001, pp. 81-99;

Latini Massimo, Sculture altomedievali inedite del Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia in Roma, in «Rivista dell’Istituto Nazionale d’Archeologia e Storia dell’Arte», 57, 2003, pp. 113-152;

Roperti Antonella, Note sulla scultura, in Bonacasa Carra Rosa Maria, Vitale Emma (a cura di), La cristianizzazione in Italia tra Tardoantico ed Altomedioevo. Atti del IX Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia cristiana (Agrigento, 20-25 novembre 2004), vol. I, Palermo 2007, pp. 411-420;

Latini Massimo, in Barberini Maria Giulia (a cura di), Tracce di pietra. La collezione dei marmi di Palazzo Venezia, Roma 2008, pp. 175-194, schede 1-29;

Ballardini Antonella, Scultura per l’arredo liturgico nella Roma di Pasquale I: tra modelli paleocristiani e Flechtwerk, in Quintavalle Arturo Carlo (a cura di), Medioevo: arte e storia, X Convegno internazionale di studi (Pavia, 18-22 settembre 2007), Milano-Parma 2008, pp. 225-246;

Lomartire Saverio, Commacini e marmorarii. Temi e tecniche della scultura tra VII e VIII secolo nella Langobardia maior, in I Magistri commacini. Mito e realtà del Medioevo lombardo. Atti del XIX Congresso internazionale di studio sull’alto medioevo (Varese-Como, 23-25 ottobre 2008), I, Spoleto 2009, pp. 151-209;

Pensabene Patrizio, Roma su Roma. Reimpiego architettonico, recupero dell’antico e trasformazioni urbane tra il III e il XIII secolo, Monumenti di antichità cristiana, XXII, Città del Vaticano 2015;

Roth-Rubi Katrin, Die frühe Marmorskulptur von Chur, Schänis und dem Vinschgau (Mals, Glurns, Kortsch, Göflan, Burgeis und Schloss Tirol), Ostfildern 2018;

Casartelli Novelli Silvana, Decoro a "Korbboden" (fondo di canestro): una nota sul «vizio di noi occidentali, della spiegazione mimetica delle immagini, anche in presenza di disegni astratti», in «Arte medioevale», 9, 2019, pp. 9-58;

Roth-Rubi Katrin, La scultura nella Rezia, il suo legame con l’Italia e il Rinascimento carolingio, in Ammirati Serena, Ballardini Antonella, Bordi Giulia (a cura di), Grata più delle stelle. Pasquale I (817-824) e la Roma del suo tempo, vol. 2, Roma 2020, pp. 111-127.