Crucifixion between the two mourners and Mary Magdalene

Pseudo Stefano da Ferrara 1425–1430

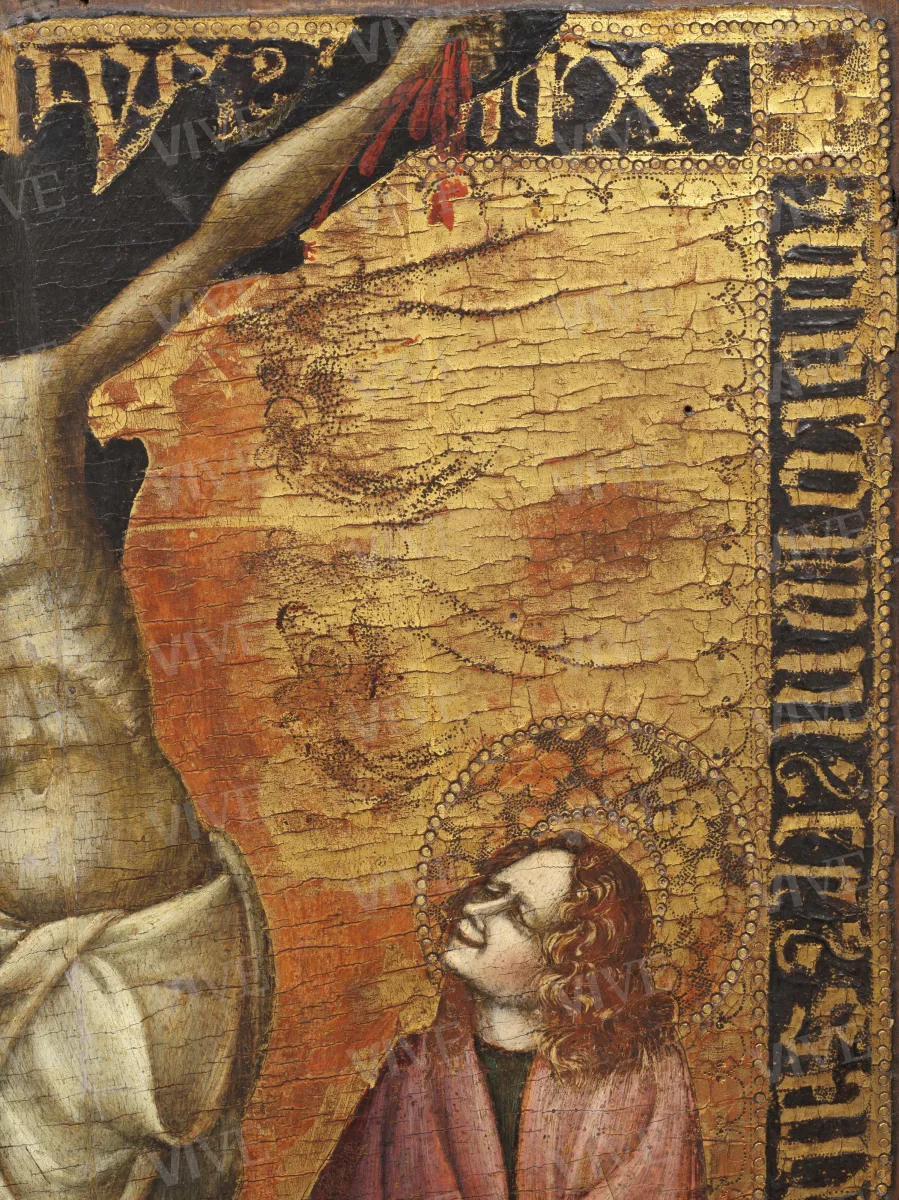

The painting portrays the Crucifixion within the rugged terrain of Golgotha, featuring Mary Magdalene at the base of the cross, and the Virgin and Saint John positioned alongside, all visibly affected by the tragic death of Christ. The anonymous artist, referenced by critics as Pseudo Stefano da Ferrara, was active during the first half of the fifteenth century in Italy's Po Valley region. Known primarily for his frescoes and panel paintings intended for private devotion, this modestly sized piece exemplifies his work.

The painting portrays the Crucifixion within the rugged terrain of Golgotha, featuring Mary Magdalene at the base of the cross, and the Virgin and Saint John positioned alongside, all visibly affected by the tragic death of Christ. The anonymous artist, referenced by critics as Pseudo Stefano da Ferrara, was active during the first half of the fifteenth century in Italy's Po Valley region. Known primarily for his frescoes and panel paintings intended for private devotion, this modestly sized piece exemplifies his work.

Details of work

Catalog entry

Christ on the cross, situated among the arid rocks of Golgotha, is depicted enduring suffering, with his hands, feet, and side still bleeding. He is surrounded by four angels entirely made of gold, each displaying expressions of sorrow, while the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist are visibly grief-stricken by the unfolding events. Mary Magdalene is shown kneeling at the base of the cross, which is represented according to the fork or “Y” typology, as described in Bonaventura's Lignum vitæ (Guerzi 2006). The upper section of the composition features an inscription in gothic lettering, rendered in gold contrasting against a brown background, and framed by two bands of regular stamps that have become difficult to decipher today (particularly the opening section on the left).

The panel, initially recorded as the work of a fifteenth-century Bolognese artist in the Relazione di Stima della Collezione Sterbini commissioned by Federico Hermanin in 1935 (see Guerzi 2006), was attributed by Santangelo (1947) to Giovanni da Modena in the early fifteenth century. This attribution was subsequently confirmed by Longhi (1950; Longhi 1955, ed. 1956), who described the Crucifix as having an expressionistic style similar to that of a Bohemian artist. The attribution was also supported by Zeri (1950; Zeri 1955) and Castelfranchi Vegas (1966).

Bottari, during a course held in 1957–1958 (and transcribed in Volpe 1958), noted the significant expressiveness of the painting in the Palazzo Venezia, which he believed was created in the 1930s. He observed that this expressiveness differed from the style of the Modenese master, suggesting that the Crucifixion should be attributed to a painter from Emilia who combined the fourteenth-century heritage of Jacopo di Paolo with the more international style of Giovanni da Modena. Padovani (1975) followed this perspective, identifying the so-called Second Master of Carpi as influencing the dramatic pathos and wide, sweeping drapery of the Crucifixion. Padovani also associated Palazzo Venezia’s Christ Praying in the Garden of Gethsemane (inv. 1023) with this master.

Volpe (1983) first established a connection between the Roman panel and the astrological frescoes in the lower section of the hall of the Palazzo della Ragione in Padua (post-1420), which Ragghianti (1972) attributed to Stefano da Ferrara. Volpe posited that this painter’s work falls between the later phases of the Gothic style in Ferrara and the initial influences of Pisanello evident in other works, although subsequent critics have reattributed these pieces: one to the Second Master of Carpi (Medica 1988) and another to Pisanello's circle (Cordellier 1996). Medica (1987) initially confirmed the attribution of the Crucifixion to Stefano da Ferrara but later rejected it (1989); Benati (1988) reaffirmed this attribution, dating the panel to around 1415 and deeming it as "earlier evidence in a completely Bolognese style." Conversely, Grandi (1987) attributed the panel to a local artist, paralleling Giovanni da Modena’s earliest phase, if not preceding it directly. Lucco (1989) removed the panel from Stefano da Ferrara’s catalog, suggesting it is more recent than Lombard and French works from the early fifteenth century, yet confirming its Bolognese origin based on halo decorations similar to those produced by Jacopo di Paolo and his son Orazio’s workshop.

Through further studies, a profile of Stefano da Ferrara from the fourteenth century has been documented in Este, Treviso, Cremona, and Padua (Boskovits 1994; Baradel 2019; Guarnieri 2021). As a result, the personality reconstructed by Volpe has been designated as “Pseudo Stefano da Ferrara” pending concrete documentary evidence.

De Marchi (1999; De Marchi 2002) has examined the role of Antonio di Pietro da Verona in the decoration of the Sala della Ragione in Padua. He recently suggested that Pseudo Stefano contributed as a collaborator to Jacopo di Paolo, who is identified as the creator of the frescoes of James the Apostle in Padua (De Marchi 2021, pp. 9–47).

Flores D'Arcais (1998, 2001) has reintroduced the proposal to identify Pseudo Stefano as an artist of Lombard and Ferrarese culture, active in the frescoes of the chapel of San Martino in Carpi (now attributed to Maestro G.Z., also known as Michele Dai Carri, according to Benati 2007). Additionally, new perspectives have emerged from Guerzi (2006), who emphasized Pseudo Stefano's adaptation following the encounter between Giovanni da Modena and Jacopo della Quercia in Bologna. This relationship is corroborated by numerous stylistic similarities from the 1420s and works related to the Porta Magna (Benati 2014; Cavazzini 2014). Comparative analyses between the Prophets of San Petronio (from the initial phase of work between 1426 and 1428, as noted by Bellosi 1983) and figures in the Paduan frescoes reveal similar traits, such as the proliferation of copious drapery and a distinctive randomness in gestures. Concurrently, the Roman Crucifixion reflects neo-fourteenth-century echoes of Jacopo di Paolo from Bologna (particularly visible in the halos) alongside Veneto influences in the Emilia region (De Marchi 1987, 1999), with a notable emphasis on the extensive use of gold embellishment. This includes angels rendered in granite on gold, an innovation attributed to Gentile da Fabriano (De Marchi 1992, 2006).

Mariaceleste Di Meo

Entry published on 27 March 2025

State of conservation

Fair. The inventory card at the museum states that the painting underwent restoration by the Istituto Centrale del Restauro shortly after the mid-1960s. During this process, wooden strips were inserted to stabilize cracks in the canvas, which remain visible on the reverse side. The rigatino technique was employed to fill gaps in the paint film, particularly along a crack in the lower left section of the painting. Furthermore, areas lacking the final varnish, such as parts of the drapery of Saint John, are still observable.

Restorations and analyses

1966–1967: restoration carried out by the Istituto Centrale del Restauro

Inscriptions

In the margin of the panel: “[…] NAZARENUS/ REX IUDEORUM ET SALVATOR.”

Provenance

Rome, Collezione Giulio Sterbini;

Rome, Collezione Lupi;

Rome, gift of Giovanni Armenise, July 15, 1940;

Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, 1940.

Exhibition history

Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Mostra della pittura bolognese del ’300, May–July 1950;

Fabriano, Spedale di Santa Maria del Buon Gesù, Gentile da Fabriano e l’altro Rinascimento, April 21–July 23, 2006.

References

Santangelo Antonino (a cura di), Museo di Palazzo Venezia. Catalogo. 1. Dipinti, Roma 1947, p. 37, fig. 52;

Longhi Roberto, Piano consistenza e significato di questa mostra, in Guida alla Mostra della pittura bolognese del ’300, catalogo della mostra (Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, maggio-luglio 1950), Bologna 1950, pp. 11-24;

Longhi, in Guida alla Mostra della pittura bolognese del ’300, catalogo della mostra (Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, maggio-luglio 1950), Bologna 1950, p. 35, n. 110;

Zeri Federico, Belbello da Pavia: un salterio, in «Paragone. Arte», 1, 1950, 3, pp. 50-52;

Longhi Roberto, Note brevi (1955), in Opere complete di Roberto Longhi, V, Officina ferrarese, Firenze 1956, pp. 193-195;

Zeri Federico (a cura di), Catalogo del Gabinetto Fotografico Nazionale. 3. I dipinti del museo di Palazzo Venezia in Roma, Roma 1955, p. 6, n. 53;

Volpe Carlo, La pittura in Emilia nella prima metà del ’400, testo delle dispense per il corso di Stefano Bottari, a.a. 1957-58, Bologna 1958, p. 38;

Castelfranchi Vegas Liana, Il gotico internazionale in Italia, Roma 1966, p. 40;

Ragghianti Carlo Ludovico, Stefano da Ferrara. Problemi critici tra Giotto a Padova, l’espansione di Altichiero e il primo Quattrocento a Ferrara, Firenze 1972;

Padovani Serena, Pittori della corte estense nel primo Quattrocento, in «Paragone. Arte», 26, 1975, 299, pp. 25-53, nota 20;

Bellosi Luciano, La “porta magna” di Jacopo della Quercia, in Bellosi Luciano, Budriesi Roberta, Fanti Mario et al., La Basilica di San Petronio, Bologna 1983, pp. 163-212;

Volpe Carlo, La pittura gotica. Da Lippo di Dalmasio a Giovanni da Modena, in Bellosi Luciano, Budriesi Roberta, Fanti Mario et al., La Basilica di San Petronio, Bologna 1983, pp. 213-294, fig. 289;

De Marchi Andrea, Per un riesame della pittura tardogotica a Venezia: Nicolò di Pietro e il suo contesto adriatico, in «Bollettino d’arte», 72, 1987, 44/45, pp. 25-66, nota 16;

Grandi Renzo, La pittura tardogotica in Emilia, in Zeri Federico (a cura di), La pittura in Italia. Il Quattrocento, I, Milano 1987, pp. 222-239, nota 28;

Medica Massimo, Giovanni di Pietro Falloppi da Modena, in Zeri Federico (a cura di), La pittura in Italia. Il Quattrocento, II, Milano 1987, pp. 644-645;

Benati Daniele, Pittura tardogotica nei domini estensi, in Benati Daniele, Bentini Jadranka (a cura di), Il tempo di Nicolò III. Gli affreschi del Castello di Vignola e la pittura tardogotica nei domini estensi, catalogo della mostra (Vignola, Rocca, 8 maggio-30 giugno 1988), Modena 1988, pp. 43-60, nota 28;

Medica Massimo, in Benati Daniele, Bentini Jadranka (a cura di), Il tempo di Nicolò III. Gli affreschi del Castello di Vignola e la pittura tardogotica nei domini estensi, catalogo della mostra (Vignola, Rocca, 8 maggio-30 giugno 1988), Modena 1988, p. 138;

Lucco Mauro, Padova, in Lucco Mauro (a cura di), Pittura nel Veneto, I, Il Quattrocento, Milano 1989, pp. 80-101, note 50-52;

De Marchi Andrea, Gentile da Fabriano: un viaggio nella pittura italiana alla fine del gotico, Milano 1992;

Boskovitz, in Rosenberg Pierre (a cura di), Hommage à Michel Laclotte. Etudes sur la peinture du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance, Milano 1994, pp. 56-67;

Medica Massimo, Stefano da Ferrara, in Lucco Mauro (a cura di), Pittura nel Veneto, II, Il Quattrocento, Milano 1989, pp. 360-361;

Cordellier Dominique, Pisanello. La princesse au brin de genévrier, Paris 1996;

Flores D’Arcais Francesca, Note sulla decorazione a fresco del Palazzo della Ragione di Padova, in Spiazzi Anna Maria, Il palazzo della Ragione di Padova. Indagini preliminari per il restauro – Studi e ricerche, Treviso 1998, pp. 11-22;

De Marchi Andrea, Tavole veneziane, frescanti emiliani e miniatori bolognesi. Rapporti figurativi tra Veneto ed Emilia in età gotica, in Marinelli Sergio, Mazza Angelo (a cura di), La pittura emiliana nel Veneto, Modena 1999, pp. 1-44;

Flores D’Arcais Francesca, Sulla decorazione interna del Palazzo della Ragione, in «Padova e il suo territorio», 90, 2001, pp. 21-24;

De Marchi Andrea, Il nipote di Altichiero, in Franco Tiziana, Valenzano Giovanna (a cura di), De lapidibus sententiae. Scritti di storia dell’arte per Giovanni Lorenzoni, Padova 2002, pp. 99-110;

Guerzi, in Laureati Laura, Mochi Onori Lorenza (a cura di), Gentile da Fabriano e l’altro Rinascimento, catalogo della mostra (Fabriano, Spedale di Santa Maria del Buon Gesù, 21 aprile-23 luglio 2006), Milano 2006, pp. 106-108, cat. II.5;

De Marchi Andrea, Gli angeli graniti: la Madonna di Perugia, in Laureati Laura, Mochi Onori Lorenza (a cura di), Gentile da Fabriano e l’altro Rinascimento, catalogo della mostra (Fabriano, Spedale di Santa Maria del Buon Gesù, 21 aprile-23 luglio 2006), Milano 2006, pp. 94-95;

Benati Daniele, Jacopo Avanzi e Altichiero a Padova, in Valenzano Giovanna, Toniolo Federica (a cura di), Il secolo di Giotto nel Veneto, Venezia 2007, pp. 385-415;

Benati Daniele, Giovanni da Modena, tra gotico e rinascimento, in Benati Daniele, Medica Massimo (a cura di), Giovanni da Modena. Un pittore all’ombra di San Petronio, catalogo della mostra (Bologna, Museo Civico Medioevale, 12 dicembre 2014-12 aprile 2015), Cinisello Balsamo 2014, pp. 15-43, nota 127;

Cavazzini Laura, Giovanni da Modena e la scultura, in Benati Daniele, Medica Massimo (a cura di), Giovanni da Modena. Un pittore all’ombra di San Petronio, catalogo della mostra (Bologna, Museo Civico Medievale, 12 dicembre 2014-12 aprile 2015), Milano 2014, pp. 69-83;

Baradel Valentina, Stefano da Ferrara, ad vocem, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, 94, 2019 (online);

De Marchi Andrea, Alla ricerca delle origini di Stefano da Verona, figlio di Jean d’Arbois: la Crocifissione von Lenbach, in «Arte Veneta», 78, 2021, pp. 9-47, nota 47;

Guarnieri Cristina, Sulle tracce di Stefano da Ferrara nella basilica del Santo a Padova, in «Il Santo», 51, 2021, 1-2, pp. 217-232.