Christ in Piety with the Symbols of the Passion and a Franciscan Friar in Adoration

Tuscan milieu Third quarter of 15th century?

This parchment, attributed to the Tuscan region during the third quarter of the fifteenth century, illustrates Christ in Piety alongside the Symbols of the Passion, with a Franciscan Friar in Adoration.

This parchment, attributed to the Tuscan region during the third quarter of the fifteenth century, illustrates Christ in Piety alongside the Symbols of the Passion, with a Franciscan Friar in Adoration.

Details of work

Catalog entry

This piece was part of the collection of the Roman cavaliere Giulio Sterbini and later belonged to the Lupi family. In 1940, Giovanni Armenise donated it to the Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia.

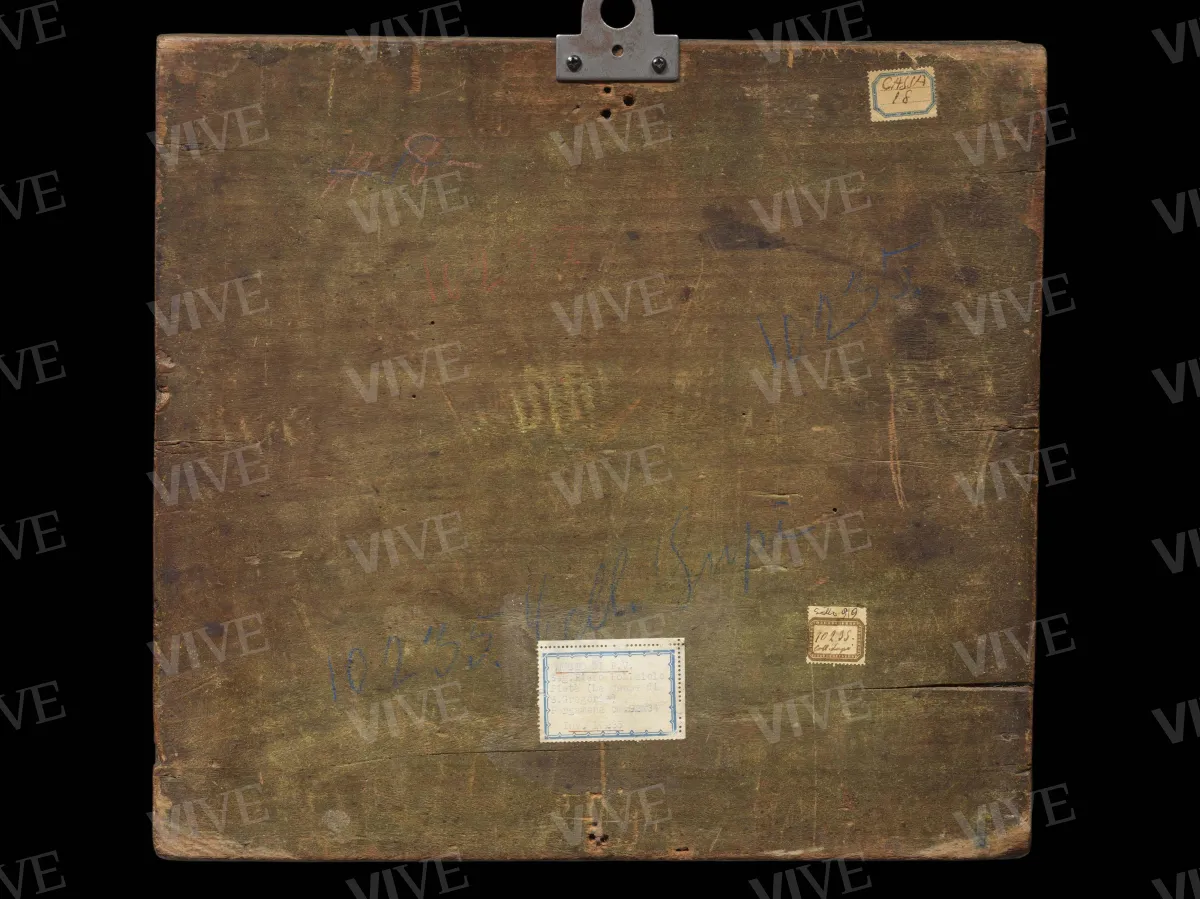

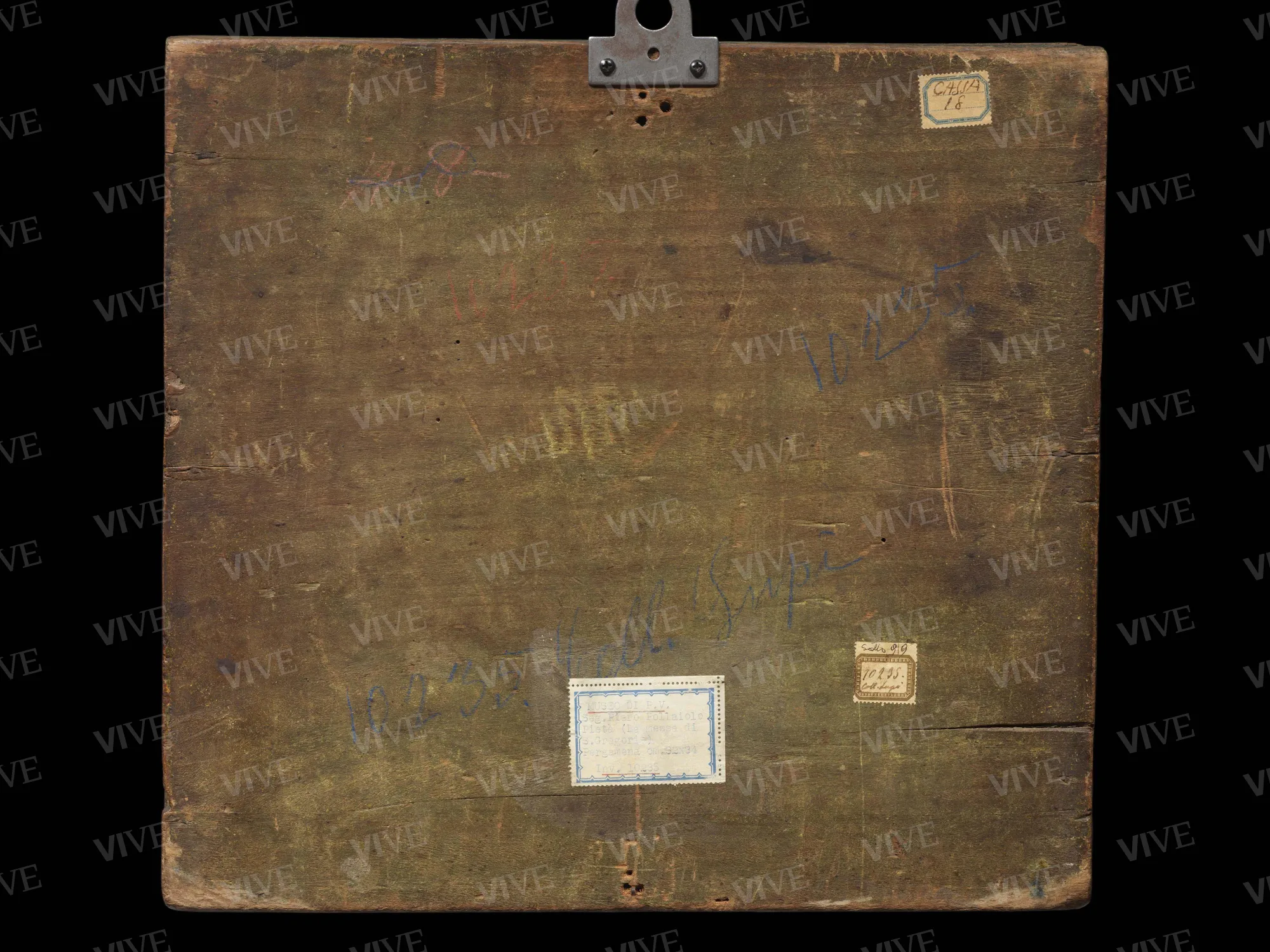

The parchment is glued to a wooden panel; the frame has a gilded finish on the front, with unusual polychrome and white veining on the sides that simulates serpentine marble. On the parchment, iconographic elements such as the tomb or the phylactery with the inscription INRI appear interrupted, making it challenging to identify the subject of the work accurately. While it has previously been interpreted as a representation of the Mass of St Gregory, it may be more accurate to consider this composition a variant of the Pietà accompanied by the Arma Christi (the symbols of the Passion), featuring a beardless Franciscan friar kneeling inside the sepulcher, who raises his left hand to his heart.

This iconography is documented in paintings and decorative arts between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, mainly in Tuscany, but also in Umbria and Veneto. Independent paintings on parchment are relatively rare: a relevant comparison, from a typological and technical perspective, is with the Christ in Pity and Episodes of the Passion, in ink and tempera on parchment, created for the Dominican order in the workshop of Beato Angelico, now in a private collection (Galli, 2009, pp. 204–207). The similarities with this piece suggest that the Palazzo Venezia work was also intended for the devotion and personal meditation of a member of the Franciscan order. The expressiveness of the friar, with “thick hands and a habit modeled by strong metallic shading,” and the “strong, incisive, rough, sometimes twisted design” of the composition led Adolfo Venturi to believe that this work was from the Ferrara area, associated with the style of Ercole de’ Roberti (Venturi 1906, p. 181). Conversely, Attilio Sabatini, following an oral indication from Roberto Longhi, considered the work “not of Ferrarese but of Florentine origin, particularly close to Pollaiuolo” (Sabatini, 1944, p. 88, note 1).

This opinion was shared by Santangelo, who associated it with the Florentine context of the second half of the fifteenth century, particularly with the circle of Piero del Pollaiolo (Santangelo, 1948, p. 36). The design’s fluidity and strength are evident in the depth of the incisions made with a metal point, into which iron-gall ink was carefully poured, likely dissolved in gummed water. This technique does not allow for any corrections and requires considerable skill; the artist then reworked some outlines with lead white and painted the iconographic elements of the composition. Notable colors include the red lacquer on the halo and tunic, and the bluish tone applied to most of the metal instruments. This same color appears more greenish in Malchus’s clothes and hat. The work is still in good condition, although the original chromatic intensity has diminished over time due to the use of inks and light varnish applied at various stages to protect the parchment. High-quality details are still visible, such as the knots in the wood of the cross, the veins in the marble of the scourging column, and the defined musculature of Christ.

Alexandre Vico

Entry published on 27 March 2025

State of conservation

Good.

Provenance

Rome, Collezione Giulio Sterbini;

Rome, Collezione Lupi;

Rome, Collezione Giovanni Armenise, 1940;

Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia, donazione 1940.

References

Farabullini David, La pittura antica e moderna e la galleria del cav. Giulio Sterbini, Roma 1874;

Venturi Adolfo, La Galleria Sterbini in Roma, Roma 1906, pp. 181-183, scheda n. 45;

Sabatini Attilio, Antonio e Piero del Pollaiuolo, Firenze 1944;

Venturi Lionello, Reconstruction of a Painting by Andrea del Castagno, in «Art Quarterly», VII, 1944, pp. 23-32;

Santangelo Antonino (a cura di), Museo di Palazzo Venezia. Catalogo. 1. Dipinti, Roma 1948, p. 36;

Zeri Federico (a cura di), Catalogo del Gabinetto Fotografico Nazionale. 3. I dipinti del Museo di Palazzo Venezia in Roma, Roma 1955, pp. 8, 17, n. 88;

Belting Hans, Das bild und sein publikum in mittelalter. Form und funktion frürer Bildtafeln der Passion, Berlin 1981;

Kren Thomas, McKendrick Scott (a cura di), Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Los Angeles 2003;

Suckale Robert (a cura di), Rudolf Berliner (1886-1967) “The freedom of Medieval Art” und andere Studien zum christlichen Bild, Berlin 2003;

Wright Alison, Between the Patron and the Market: Production Strategies in the Pollaiuolo Workshop, in Fantoni Marcello, Matthew Louisa C., Matthews-Griego Sara F. (a cura di), The Art Market in Italy (15th-17th Centuries). Il Mercato dell’Arte in Italia (secc. XV-XVII), Modena 2003, pp. 225-236;

Galli, Aldo, Arma Christi (Cristo in pietà ed episodi della Passione), in Zuccari Alessandro, Morello Giovanni, Simone Gerardo (a cura di), Fra Angelico. L’alba del Rinascimento, catalogo della mostra (Roma, Musei Capitolini, 8 aprile-5 luglio 2009), Milano 2009, pp. 204-207;

Christiansen Keith, The Man of Sorrows. Michele Giambono (c. 1430) [Scheda], The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012. on line: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436498;

Galli Aldo, La sorte dei Pollaiuolo, in Di Lorenzo Andrea, Galli Aldo (a cura di), Antonio e Piero del Pollaiuolo. “Nell’argento e nell’oro, in pittura e nel bronzo...”, catalogo della mostra (Milano, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, 7 novembre 2014-16 febbraio 2015), Milano, 2014, pp. 25-78;

Seccaroni, Claudio, Alcune considerazioni sui supporti costituiti da pietra, tovagliati e carta o pergamena incollate su tavola, in «Kermes», 31, 111-112, 2019, pp. 21-30.