Christ on the Cross

Expressionist Master of Santa Chiara Ca 1320–1330

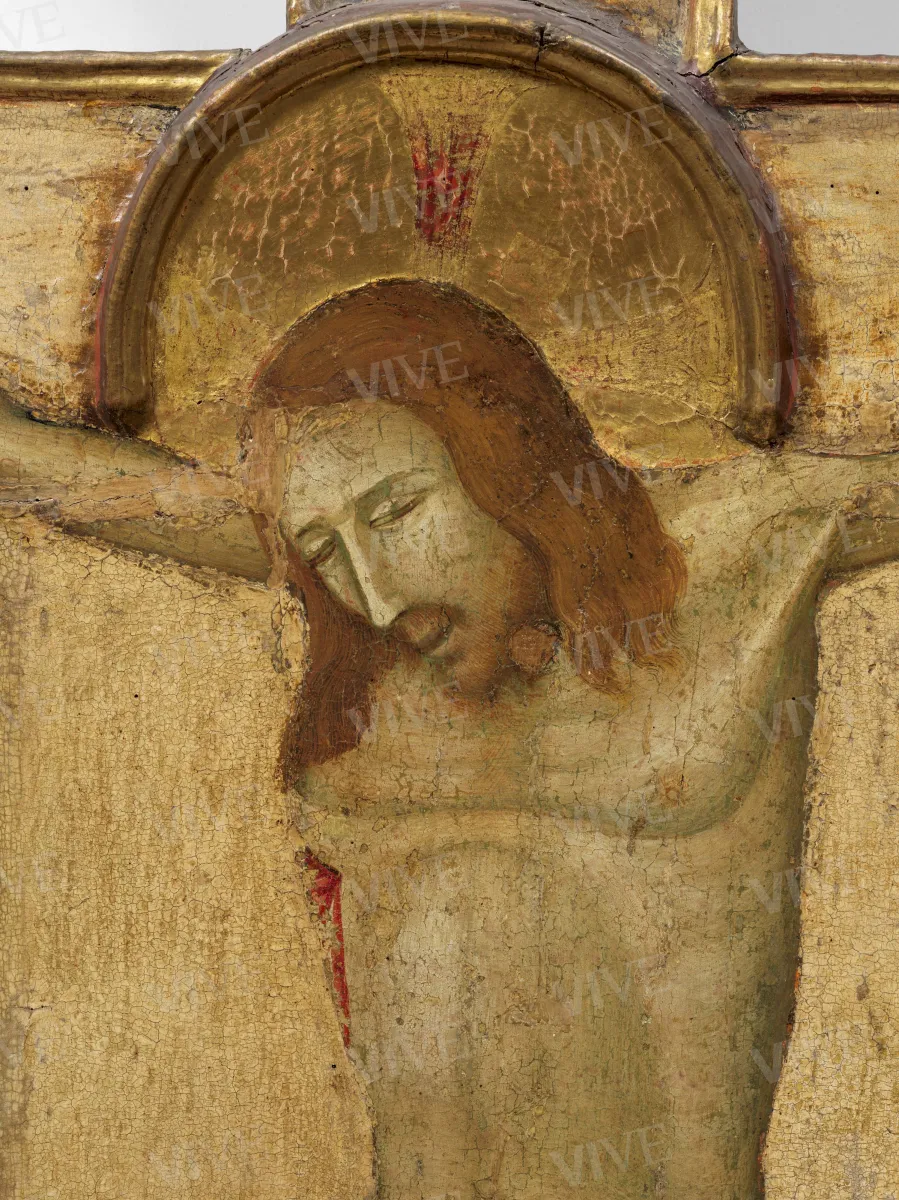

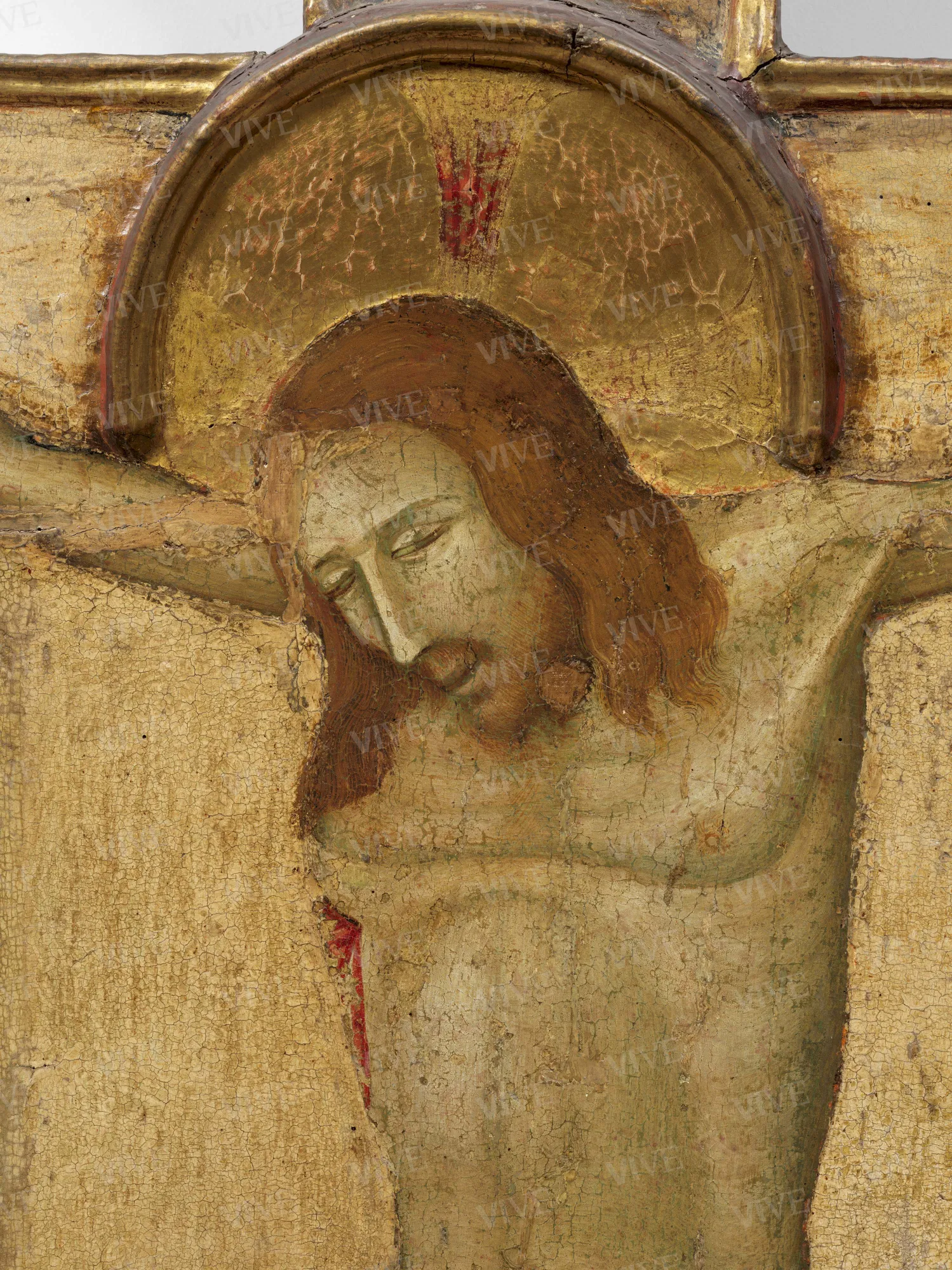

The cross is very damaged and is therefore not easy to interpret. The complex shaping of the support is articulated in the wide central tabernacle, which houses the figure of Christ, in the three-lobed finials of the crossbeam with the Virgin and Saint John, and in the ends of the uprights whose quadrangular panels have triangular extensions that are repeated several times around the perimeter of the cross. The figure of Christus patiens, with his gaunt, bruised body, and the figures of the mourners are clearly derived from a fourteenth-century model, certainly from central Italy and datable to the first decades of the century.

The cross is very damaged and is therefore not easy to interpret. The complex shaping of the support is articulated in the wide central tabernacle, which houses the figure of Christ, in the three-lobed finials of the crossbeam with the Virgin and Saint John, and in the ends of the uprights whose quadrangular panels have triangular extensions that are repeated several times around the perimeter of the cross. The figure of Christus patiens, with his gaunt, bruised body, and the figures of the mourners are clearly derived from a fourteenth-century model, certainly from central Italy and datable to the first decades of the century.

Details of work

Catalog entry

The cross, which arrived at the Palazzo Venezia museum in 1940, is currently very damaged and therefore not easy to interpret stylistically. The complex shaping of the support is articulated in the wide central tabernacle, which houses the figure of Christ, in the three-lobed terminals of the crossbeam with the Virgin and Saint John, and in the ends of the uprights whose quadrangular panels have triangular extensions that occur several times around the perimeter of the cross. The figure of Christus patiens in the center, with his gaunt, bruised body and suffering face, and the mournful figures of the Virgin and Saint John, despite their poor state, are clearly derived from a fourteenth-century model, certainly from central Italy and datable to the first decades of the century. In the final decades of the nineteenth century, the work was radically restored, where the entire painted surface was removed and transported to another panel that, though historically coeval, was unsuitable to the figures. The outline of the cross, the haloes, the bottom of the tabernacles, and terminals were therefore lost, and were subsequently re-drawn from scratch. The images were covered with a thick layer of color that hid the painting’s original elements, as can be seen from a photo taken before the restoration (Brugnoli 1968; Brugnoli 1970, p. 80; Santanicchia 2009, p. 205, no. 49). In 1969, the cross was once again restored and, although much damaged, it became somewhat legible again. On that occasion, Boskovitz’s original hypothesis from 1968 was confirmed, and that is that the artifact belongs to the corpus of the Expressionist Master of Santa Chiara, a painter who owes his name to the frescoes executed in the right transept and in the sails of the basilica of Santa Chiara in Assisi (Boskovitz 1971, p. 129, note 26).

Prior to its acquisition by Palazzo Venezia, the panel was in the Roman collection of Giulio Sterbini, a prominent figure in the capital’s antiquarian trade and owner of a large number of works by Italian Primitives, a nucleus of which, upon his death, was donated through the banker Giovanni Armenise to Palazzo Venezia (Morozzi 2006, pp. 908–915). However, the work is not mentioned in the two oldest publications dealing with the Sterbini collection, Farabulini’s 1874 description and the gallery catalog edited by Adolfo Venturi (1906). However, due to the illegibility of the painting, which was heavily tampered with during the nineteenth-century restoration, the panel may not have been taken into account in the descriptions, which present fewer works than those actually in the collection (Santanicchia 2009, p. 205).

In the 1848 Palazzo Venezia catalog (Santangelo 1948, p. 25), the work was dated to around 1480 and considered “of secondary interest which a very bad restoration renders ill-judged.” It is also noted that the Sterbini collection reported it to be Umbrian, which might allude to the painting’s original provenance (Boskovitz 1971, p. 129, note26).

Modern critics agree on the attribution of the cross to the Expressionist Master of Santa Chiara (Brugnoli 1968; Brugnoli 1970, pp. 11 ff.; pp. 80–83; Boskovitz 1971; Todini-Zanardi 1980; Manuali 1982; Angelini 1988, p. 88; Lunghi 1995; Neri Lusanna 2009). Todini and Zanardi state that it should be dated to the third decade of the fourteenth century because of the muted tones of the coloring. Restoration has revealed traces of lapis lazuli blue and silver leaf along the contoured margins of the figures, enough to imply a “deep-blue background in the outline of the cross’s woodwork and a Mecca gilding of the background” (Brugnoli 1968, p. 81).

Valentina Fraticelli

Entry published on 12 February 2025

State of conservation

Mediocre.

Restorations and analyses

Late nineteenth century: the entire pictorial surface was detached and transported onto another panel, which, though coeval, was unsuitable to accommodate the figures. The outline of the cross, the haloes, and the bottom of the boards and terminals were therefore lost, and were subsequently re-drawn from scratch. The images were covered with a thick layer of color that obfuscated the original painting’s elements.

In 1969, a new restoration brought back the work’s original aspect.

Provenance

Rome, Collezione Giulio Sterbini;

Rome, Museo di Palazzo Venezia, since 1848.

Exhibition history

Rome, Complesso del Vittoriano, Giotto e il Trecento. “Il più Sovrano Maestro stato in dipintura,” March 6–June 29, 2009.

References

La pittura antica e moderna e la galleria del cav. Giulio Sterbini, Farabulini David, Roma 1874;

Venturi Adolfo, La galleria Sterbini in Roma: saggio illustrativo, Roma 1906;

Museo di Palazzo Venezia. Catalogo. 1. Dipinti, Santangelo Antonino (a cura di), Roma 1947;

Longhi Roberto, In traccia di alcuni anonimi trecentisti, in «Paragone», 14, 1963, 167, pp. 3-16;

Brugnoli Maria Vittoria, Recupero di un crocifisso trecentesco nel Museo di Palazzo Venezia, in «Bollettino d'arte», 1968, pp. 80-83;

Brugnoli Maria Vittoria, in Mostra dei restauri 1969, catalogo della mostra, (Palazzo Venezia, aprile-maggio 1970), Roma 1970, pp. 11-13;

Boskovits Miklós, Un pittore "espressionista" del Trecento umbro, in Storia e arte in Umbria nell'età comunale, Atti del VI convegno (Gubbio, 26-30 maggio), Perugia 1971, pp. 115-130;

Todini Filippo, Zanardi Bruno, La Pinacoteca comunale di Assisi, Firenze 1980;

Manuali Giovanni, Aspetti della pittura eugubina del Trecento: sulle tracce di Palmerino di Guido e Angelo di Pietro, in "Esercizi", 5, 1982, pp. 5-19;

Angelini Alessandro, Espressionista di Santa Chiara: Crocefissione e Cristo in Pietà, in Bellosi Luciano (a cura di), Umbri e Toscani tra Due e Trecento, catalogo della mostra (Torino, 16 aprile-28 maggio 1988), Torino 1988, pp. 81-89;

Todini Filippo, La pittura umbra dal Duecento al primo Cinquecento, Milano 1989;

Lunghi Elvio, La decorazione pittorica della chiesa, in Bigaroni Marino, Meier Hans-Rudolf, Lunghi Elvio, La Basilica di S. Chiara in Assisi, Ponte San Giovanni (Pg), 1994, pp. 137-282;

Morozzi Luisa, Da Lasinio a Sterbini. Primitivi in una raccolta romana di secondo Ottocento, in Adembri Benedetta (a cura di), Aeimnestos. Miscellanea di studio per Mauro Cristofani, Firenze 2006, pp. 908-915;

Neri Lausanna Enrica, Giotto e la pittura in Umbria. Rinnovamento e tradizione, in Tomei Alessandro (a cura di), Giotto e il Trecento. "Il più Sovrano Maestro stato in dipintura", catalogo della mostra (Roma, Complesso del Vittoriano, 6 marzo-29 giugno 2009), Milano 2009, pp. 51-62;

Santanicchia Mirko, Maestro espressionista di Santa Chiara, in Tomei Alessandro (a cura di), Giotto e il Trecento. "Il più Sovrano Maestro stato in dipintura", catalogo della mostra, (Roma, Complesso del Vittoriano, 6 marzo-29 giugno 2009), Milano 2009, p. 215.