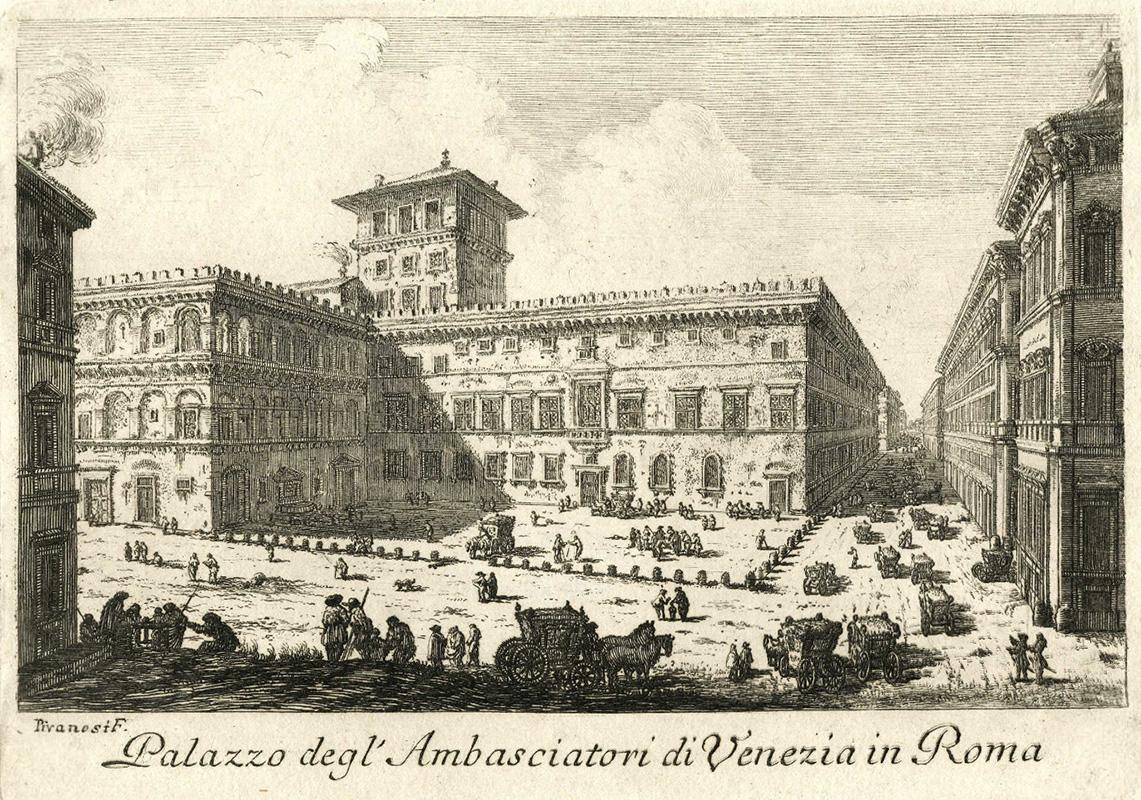

Embassy of the Republic of Venice

The transfer of part of the building to the Republic of Venice produced a marked change to the palazzo, which then also became an important diplomatic seat

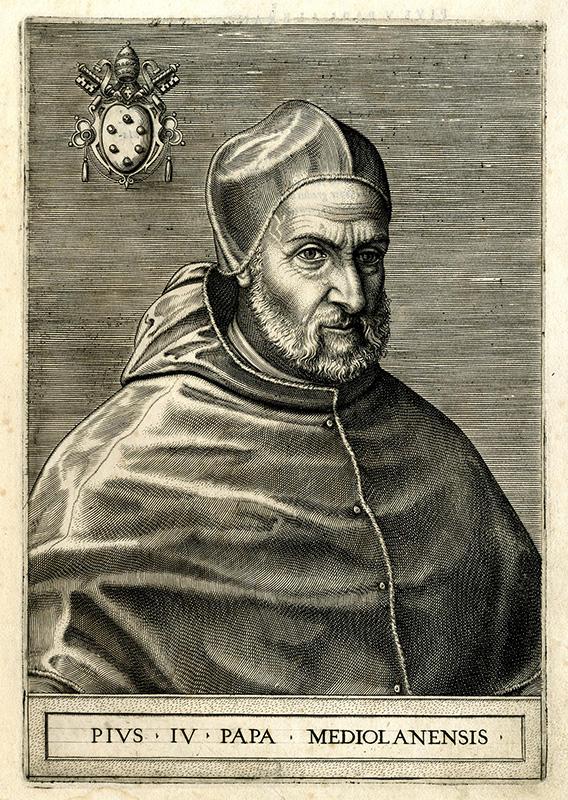

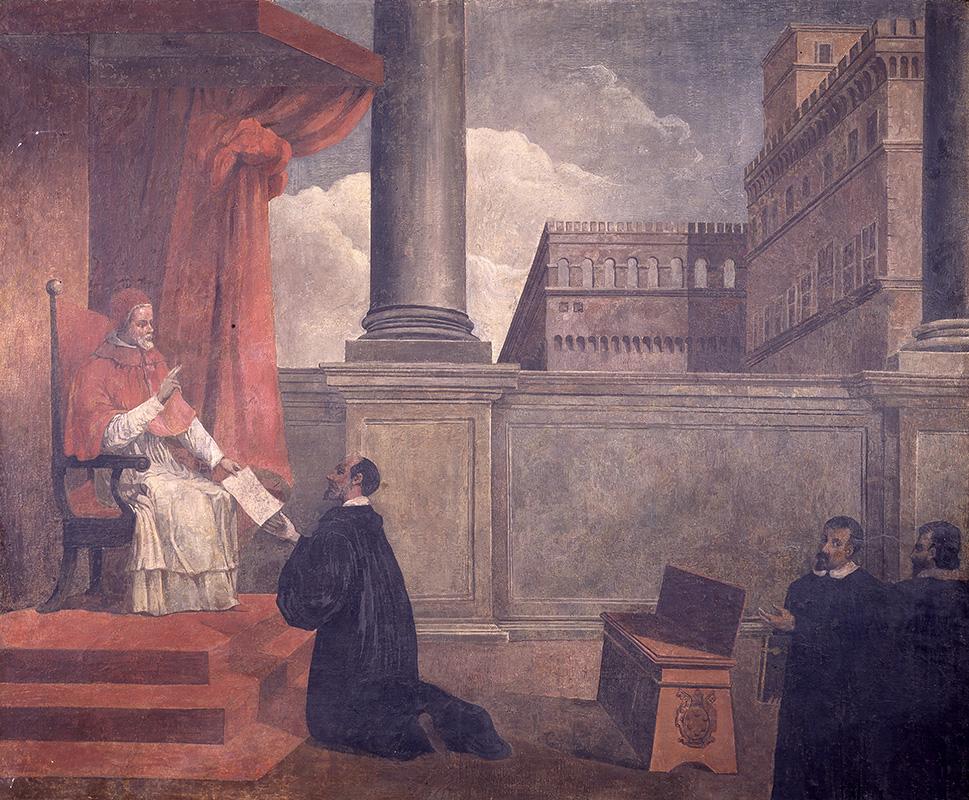

From the very beginning, the building spoke Venetian: Thus the Basilica of San Marco and the faithful who prayed there, the founder of the palace and his immediate successor, Pietro and Marco Barbo, and almost all the titular cardinals. On 10 June 1564, Pope Pius IV (1559-1565) took a further step: the Serenissima obtained the building as a gift, on condition that it was responsible for the maintenance costs. The formal handover dates to early July: from that moment the Palazzo of San Marco began to be called Palazzo Venezia.

The official entry into the palace of the ambassadors of the Republic of Venice takes place in October 1564. The first, Giacomo Soranzo (1518-1599), settled in the wing located towards the south-east: considered of greater prestige, the wing included the Barbo Apartment and the monumental rooms over Piazza Venezia, the tower bordering the basilica and the Palazzetto, formerly the viridarium.

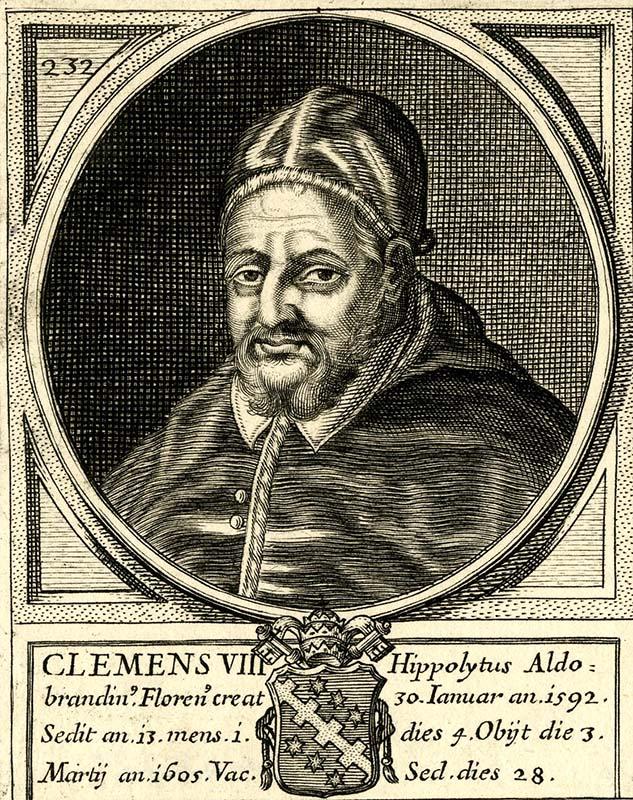

The previous occupants of the building reacted in different ways. Until Clement VIII (1592-1605), that is to say until the new, large residence on the Quirinale became habitable, the popes continued to be present without interruption in Palazzo Venezia, especially in summer, willingly taking advantage of the rooms which were graciously granted to them by the diplomatic staff. At that point, the Venetian ambassadors were forced to find alternative arrangements.

As for the titular cardinals of San Marco, the concession of the palace to the Serenissima aroused a sense of bitterness. Although they were themselves almost always Venetians by birth, they felt somehow cheated of an exclusive right of residence that they believed had by now been acquired. The cardinals, perched at the opposite end of the building, in the area that today belongs to the Cybo Apartment and the Altoviti Room, started a sort of 'cold war' with the ambassadors, made up of small and big slights, almost always originating precisely from issues of space.

The first San Marco titular who had to deal with the ambassadors of the Venetian Republic was Cardinal Francesco Pisani (1494-1570). Pisani, a member of a noble Venetian family, had worn the cardinal purple since 1517. Until then, in reality, his conduct had been much more inclined to pleasure and leisure than to prayer, so much so that he had already given birth to a natural daughter, Giulia. The cardinal's office, in addition to costing his parents about 20,000 ecus, radically influenced this state of affairs, transforming Pisani into a fixed star of the Roman ecclesiastical landscape, now oriented in the direction of the Counter-Reformation.

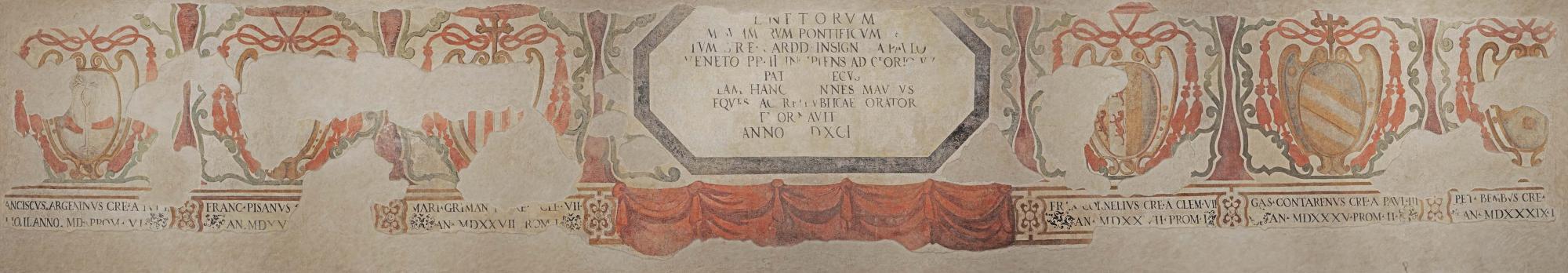

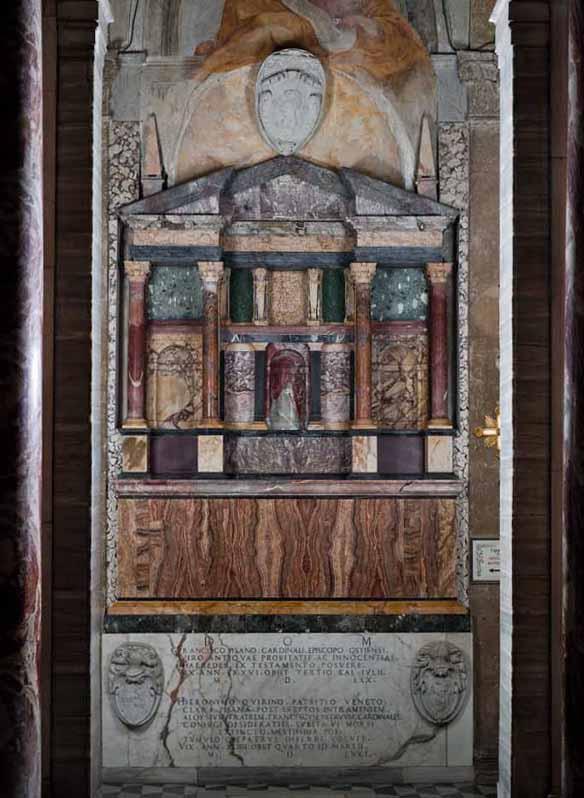

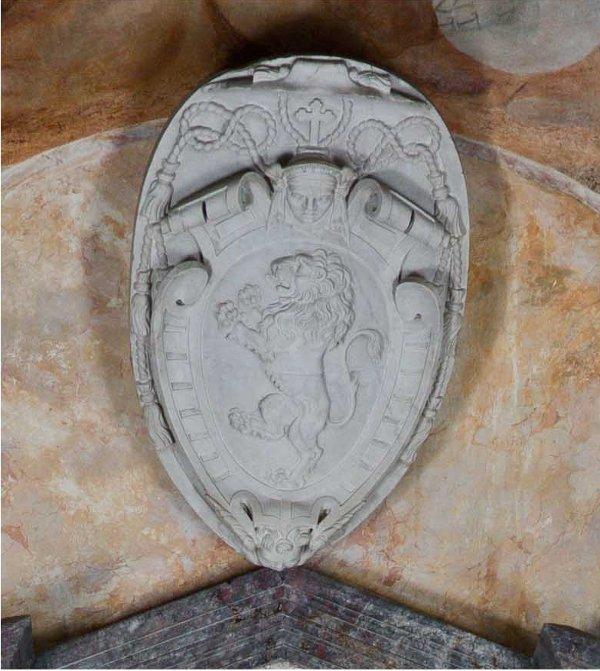

Having obtained the title of San Marco in 1527 together with the attached right of residence in the rear palace, Cardinal Pisani developed a growing and profound sense of attachment to the building. Having been denied the possibility of using the Barbo Apartment and the monumental rooms, he asked and obtained from the Republic of Venice to at least bear the costs of renovating the wing on today's Via del Plebiscito, by the Cybo Apartment and to create a new reception room, a part of which was subsequently transformed into the Altoviti Room. Many works in the palace are linked to his person, including some frescoes by Girolamo Muziano (1532-1592). Finally, in the Basilica of San Marco it is possible to admire his funeral monument, a triumph of precious polychrome marbles created in 1571 by Giovanni Marchesi da Saltrio.

The so-called Venetian Interdict occurs between 1605 and 1607; that is a dispute of a legal and then diplomatic nature that saw the Republic of Venice opposed to the Papal Curia. The war, which began with a thorny judicial case involving two priests, took on a very hard outline, so much so as to determine the breakdown of relations between the parties and also the abandonment of Palazzo Venezia by the ambassadors of the Serenissima.

Cardinal Giovanni Dolfin (1545-1622) became a part of this difficult situation. Dolfin, appointed titular of San Marco on 1 June 1605 by the new pontiff, Paul V Borghese (1605-1621), took advantage of the forced absence of the Venetian ambassadors to expand into their apartments and to expropriate them. On their return, when the representatives of the Serenissima walked into the Sala Regia they were astonished: the cardinal had closed them out, double-locking the entrance.

The history of Palazzo Venezia is often intertwined with high-profile personalities. One of the most brilliant ones was undoubtedly Cardinal Angelo Maria Querini (1680-1755), titular of the Basilica of San Marco from 1728 to 1748 and in commendam until 1755. Querini, the second son of two ancient and wealthy families of the Venetian aristocracy, particularly distinguished himself in the field of erudite studies, entering into relationships with some of the most eminent intellectuals in Europe, from Domenico Passionei to Isaac Newton and Nicolas Malebranche.

Cardinal Querini always had a particular affection for Brescia, where he had spent nine years studying at the Jesuit college between 1687 and 1696, and where he returned whenever he could. As cardinal titular, however, he also left a profound mark on Palazzo Venezia. Among other things, his name is linked to a summer residence, built using an unfinished tower and the roof of the crenelated passage along via degli Astalli, now known as the Passetto dei Cardinali (The Cardinals’ Passageway). As for the western elevation of the garden, the cardinal had a statue of San Pietro Orseolo, first doge of Venice, canonised in 1731, placed in a niche.

On 8th November 1710, the Republic of Venice appointed Lorenzo Tiepolo (1673-1742) as ambassador to the papal court. He arrived on 25th July 1711 and remained until 1713. Tiepolo had objectively more important and delicate missions to his credit: in the Paris of Louis XIV (1638-1715), he had written in one of his dispatches about a Europe devastated by wars, for which "human prudence cannot conjecture that which could be the end".

The years spent in Rome, relatively quiet from a diplomatic point of view, gave Tiepolo the opportunity to dedicate himself calmly to the renovation of Palazzo Venezia. He ordered emergency works to be carried out in the current Sala delle Battaglie, for which he turned to Carlo Fontana (1638-1714), Bernini's best student in the field of architecture.

In 1713, the Serenissima appointed Nicolò Duodo (1657-1742) as ambassador to the Holy See. Contrary to what had occurred with his predecessor Lorenzo Tiepolo, this destination represented the most important and prestigious assignment of his diplomatic career. The approximately six years he spent in Rome ended with a recognition in the field of culture: in 1719 the assembly of the Arcadians welcomed Duodo into its ranks, with the name of Aclasto Eurotano.

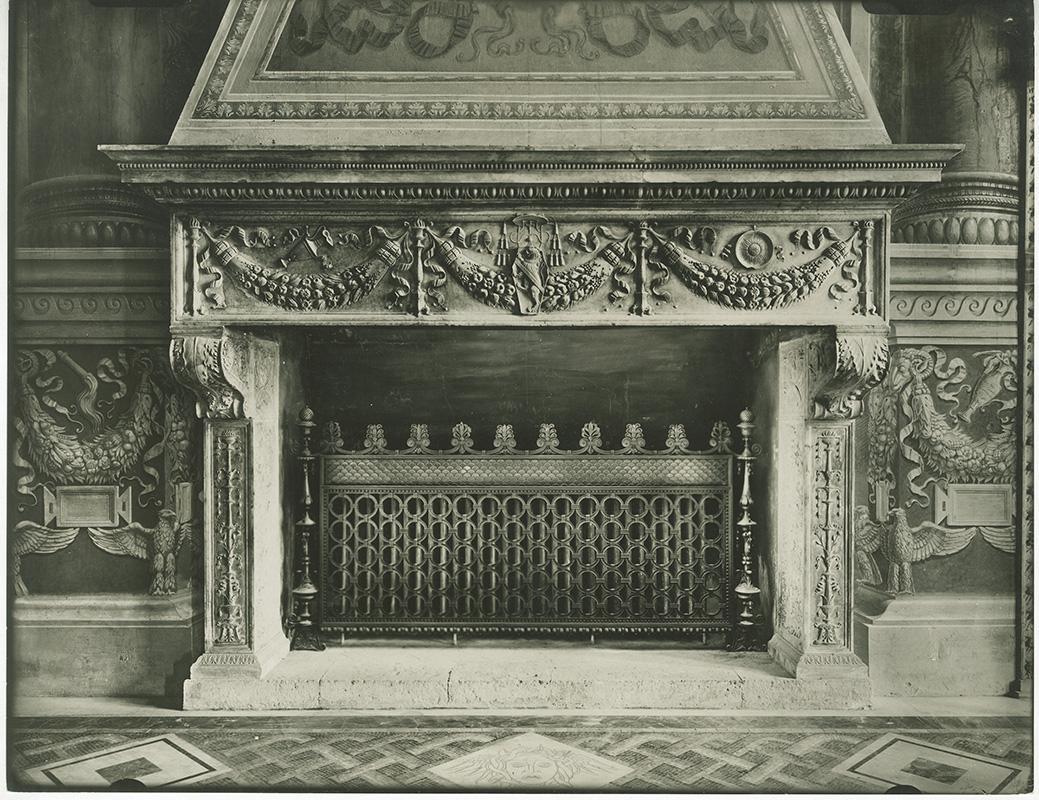

The ambassador left extensive traces inside Palazzo Venezia. Having permanently repaired the roofs of today's Sala delle Battaglie, he moved on to the Sala del Mappamondo: divided into two distinct rooms, the "Sala del Camin Grande" and the "Sala del Camin Piccolo", he had a partition built there, thus obtaining a mezzanine "for the convenience of family members ”, and finally modified one of the windows, in order to add a balcony overlooking Piazza Venezia.

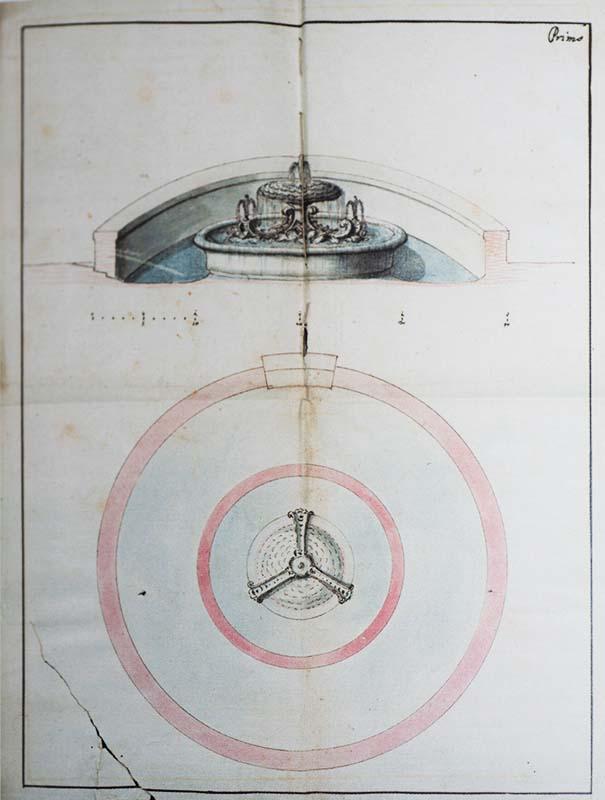

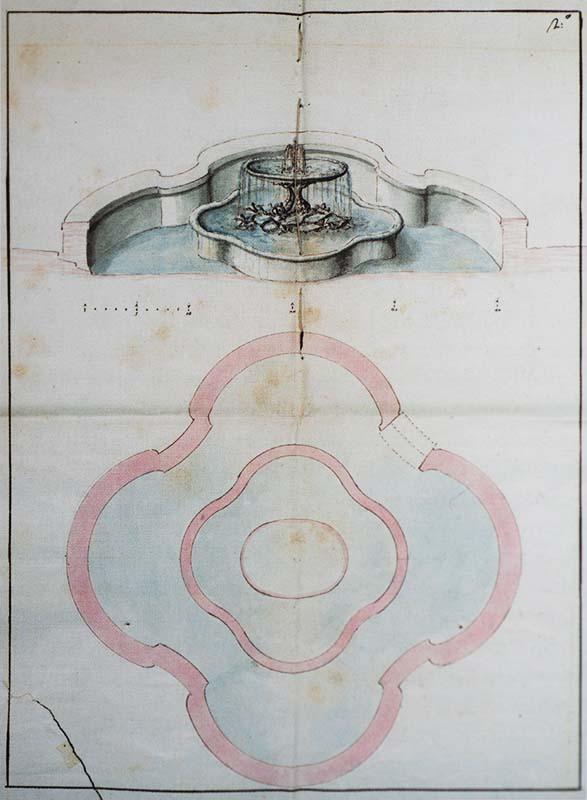

In 1729, sculptor Carlo Monaldi (1683-1760) was commissioned a large fountain for the main courtyard of the building. The idea of bringing water directly to the palace belonged to the Venetian cardinal Pietro Ottoboni (1610-1691), titular of San Marco from 1670 to 1677: ascending to the papal throne in 1689 with the name of Alexander VIII, Ottoboni had remembered the building, giving it six fluid ounces of water from the Acqua Paola aqueduct free of charge. Forty years later, the idea was translated into a concrete work thanks to the Ambassador of the Republic Barbon Morosini. The work, completed in 1730 and still in the centre of the courtyard, transposed into marble one of the most famous and important ceremonies of the Republic, Venice’s Marriage Of The Sea Ceremony.

Forty years later, the idea was translated into a concrete work thanks to the Ambassador of the Republic Barbon Morosini. The work, completed in 1730 and still in the centre of the courtyard, transposed into marble one of the most famous and important ceremonies of the Republic, Venice’s Marriage Of The Sea Ceremony.

For the entire duration of the eighteenth century, Palazzo Venezia continued to be frequented by artists. In many circumstances they were Venetian artists, who turned to the ambassador of the time in search of protection.

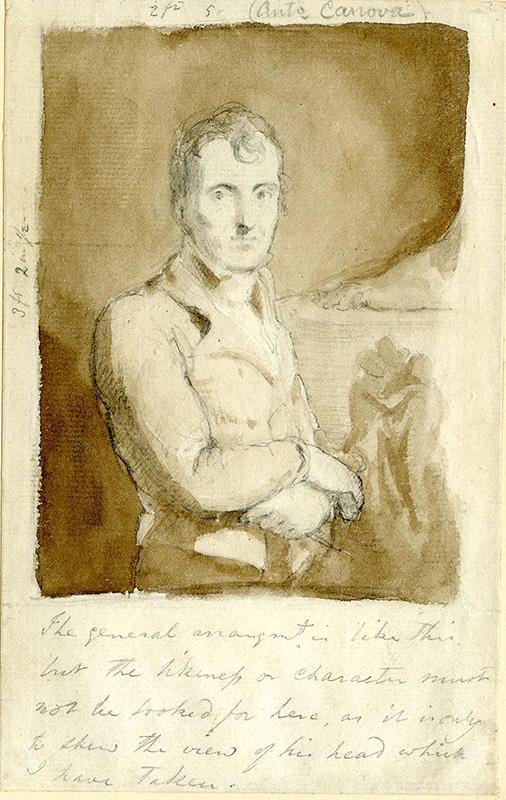

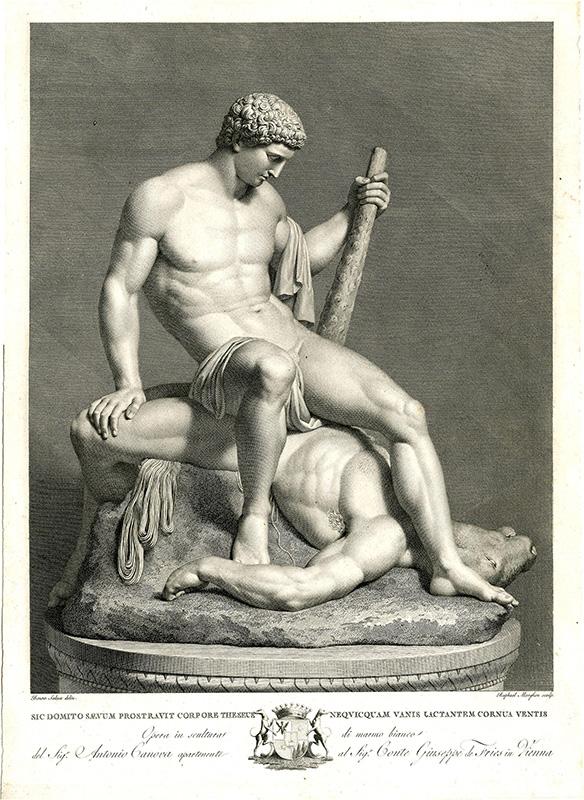

This line culminated with Antonio Canova (1757-1822). The great sculptor, who arrived in Rome in 1779, was well received by ambassador Girolamo Zulian (1730-1795). Zulian went down in history as a great "art connoisseur": immediately realising the artist's quality, the diplomat offered him a "house (...) room for his studio", plus a monthly pension of 25 silver ducats. Canova immediately took advantage of the hospitality, spending the next four years in the building. There is more. Zulian provided the marble block for one of the artist's first masterpieces, Theseus and the Minotaur: the work, sculpted inside Palazzo Venezia and completed in 1782, is now in the Victoria and Albert London museum.