Austria, France and then Austria again.

The end of the Republic of Venice opened a new phase for the building: except for the revolutionary period, the palace became the seat of the ambassadors of the Austro-Hungarian Empire for over a century

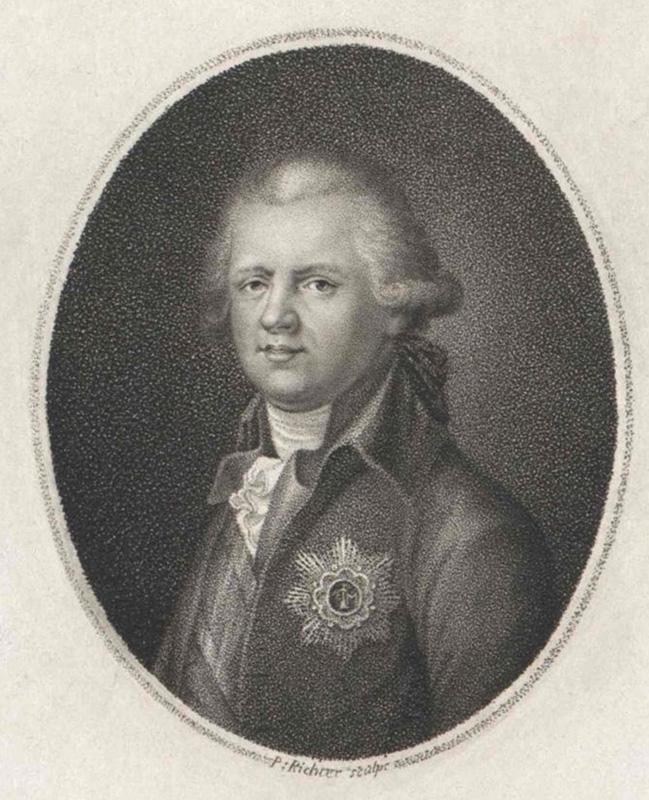

On 17 October 1797, general Napoleon Bonaparte and count Johann Ludwig Josef von Cobenzl signed a peace treaty: Bonaparte represented the Army of Italy of revolutionary France, Cobenzl the Habsburg Empire. The treaty, signed in the town of Campoformido in Friuli and therefore usually called the Treaty of Campoformio, included among the clauses the end of the Republic of Venice and the transfer to Austria of all its possessions, including of course the seat of its embassy in Rome. From 1st January 1798, Palazzo Venezia became the seat of Austrian diplomacy at the Papal State: after more than three centuries, the lion of St. Mark was lowered, giving way to the Habsburg eagle.

The Holy Roman Empire flag remained in place for a handful of years. The birth of the Kingdom of Italy on 17th March 1805, the coronation of Napoleon on 26th May 1805 and the inclusion of Venice in 1806 caused a rapid change here too. The Palazzo of San Marco thus became the seat of the representative of the Kingdom of Italy until its break-up, which took place in 1814.

The parenthesis of the Italic Kingdom was of considerable importance for Palazzo Venezia. In the short period it spent in French hands, the figure of Giuseppe Tambroni (1773-1824), a scholar and an art critic, as well as a diplomat, stands out. Appointed consul of the Kingdom of Italy in Civitavecchia on 11th March 1811, Tambroni, who had the right to reside in the building, thanks also to the support of Antonio Canova (1757-1822) worked hard in terms of artistic promotion. The result was the project for an Academy of Fine Arts in the Italic Kingdom: the Academy, located inside the Palazzetto, was to offer to the artists recommended by the Academies of Fine Arts of Milan, Venice and Bologna the opportunity to spend a three-year study period in Rome, subsequently extended to four years.

The artists supported by Tambroni through the Academy include Francesco Hayez (1791-1882). Hayez, a favourite of count and art historian Leopoldo Cicognara (1767-1834), arrived in Rome in 1809, spending here years that were very important for his stylistic training. Here he created, among other things, Rinaldo and Armida, today in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, where he re-interpreted the colourism of Tisiano Vecellio in a romantic key. During the period spent at Palazzo Venezia, the artist also found time to carry on a clandestine love affair with a young married woman, the daughter of the embassy butler, and for this he suffered an assault by her husband. Canova immediately ran to his aid, and, to silence the scandal advised, or rather ordered, the artist to take cover in Florence, at least for some time.

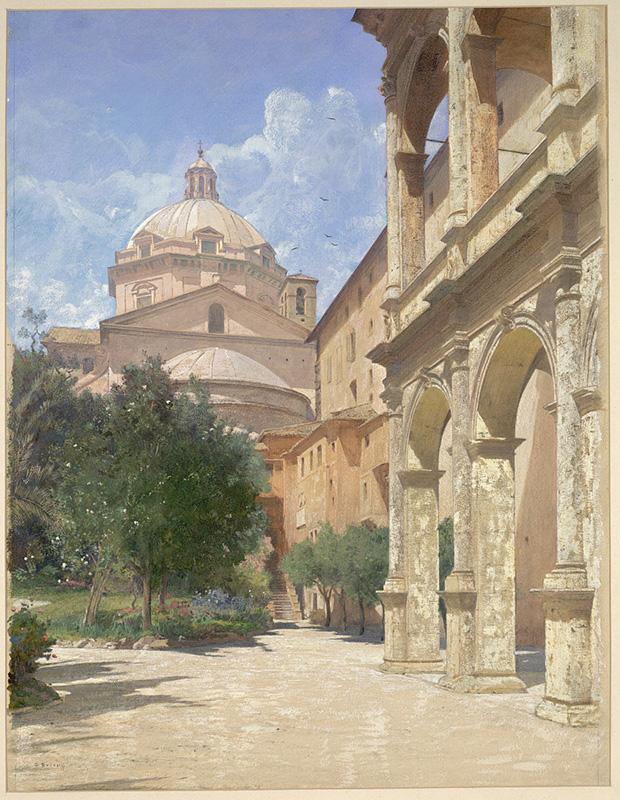

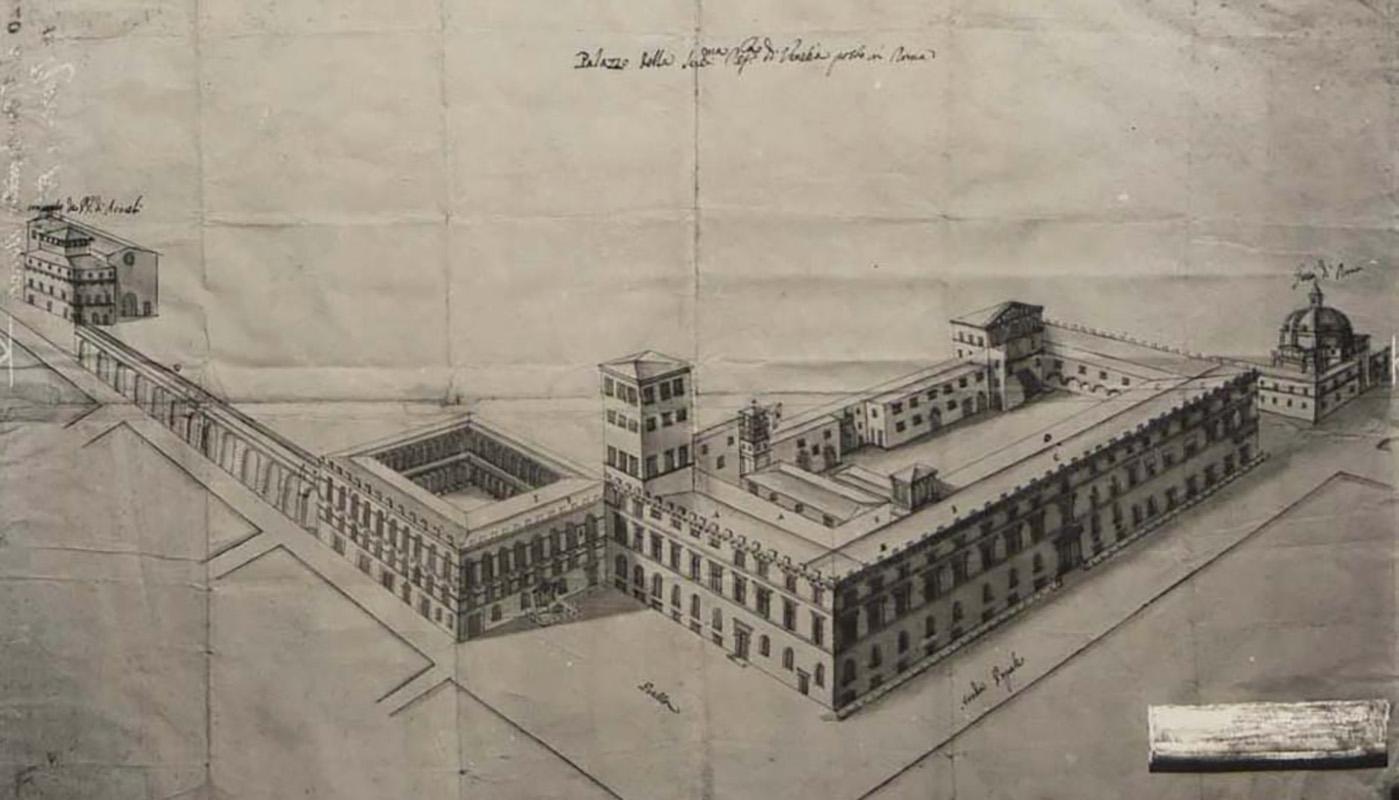

In 1815, with the Restoration sanctioned by the Congress of Vienna, the palace returned to Austrian hands. The government of Vienna kept the two main functions of the building, diplomatic and artistic, essentially unchanged. Its premises continued to house a small but thriving colony of scholarship artists: the pensionnaires (Academy pensioners). In 1871, according to the account of Count Ambassador Ferdinand von Trauttmansdorff-Weinsberg, of the total of eleven studios, seven were located in the tower, three in the rear wing of the first floor and one on the ground level, ideal for large and heavy sculptures. The many who over the years benefited from the hospitality of Palazzo Venezia also included the well-known landscape architect Othmar Brioschi (1854-1912), as revealed by the recent discovery of a series of shots by amateur photographer Paul Lindner.

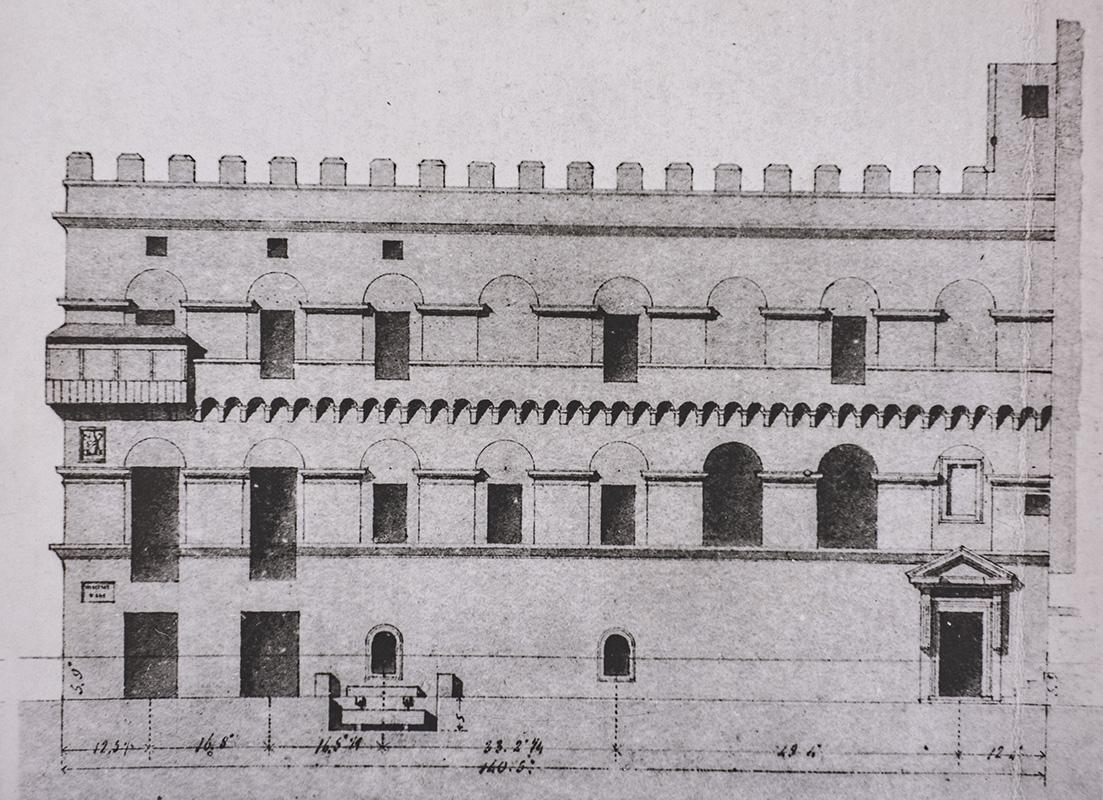

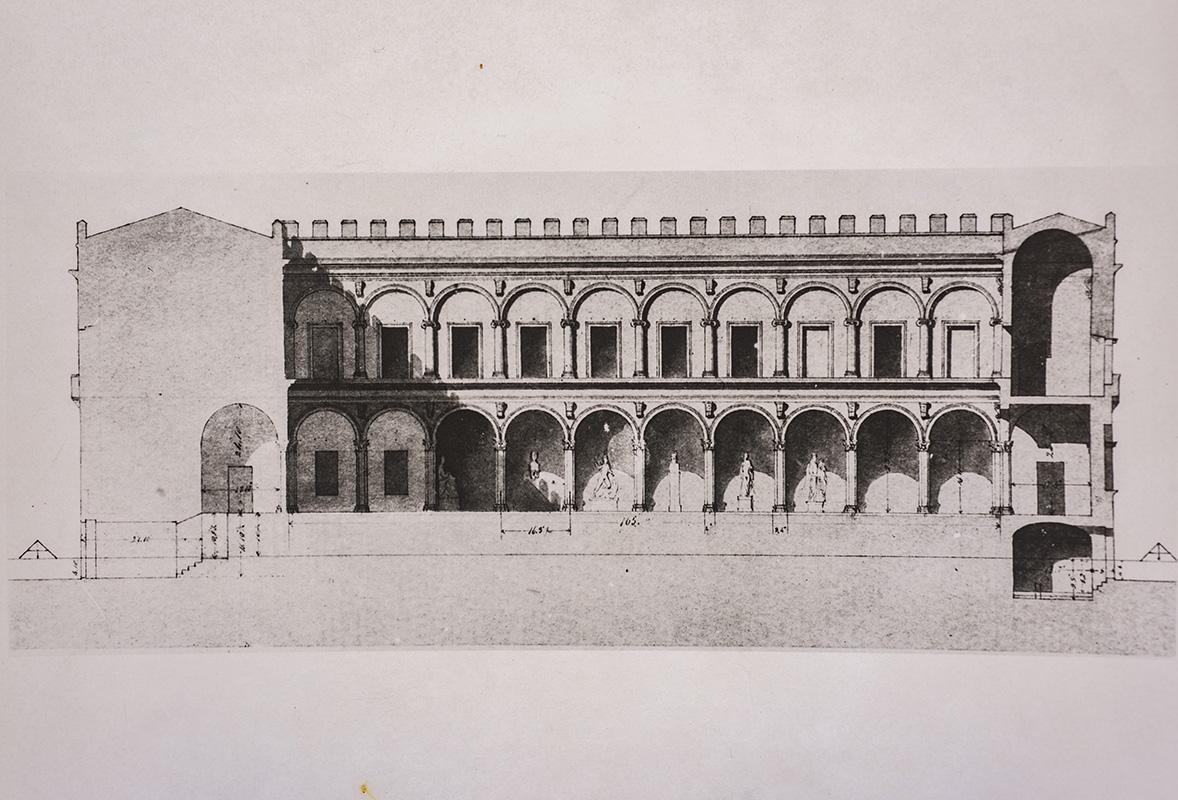

Between 1856 and 1859, architect Antonín Barvitius from Prague, already living in Rome at the Vienna Academy, was entrusted with the restoration of the building: on the one hand he carried out a survey of the structural conditions and reinforced the building; on the other, he updated the façade, trying to make it as consistent and symmetrical as possible, and created partition walls in the monumental rooms starting with the Sala Regia.

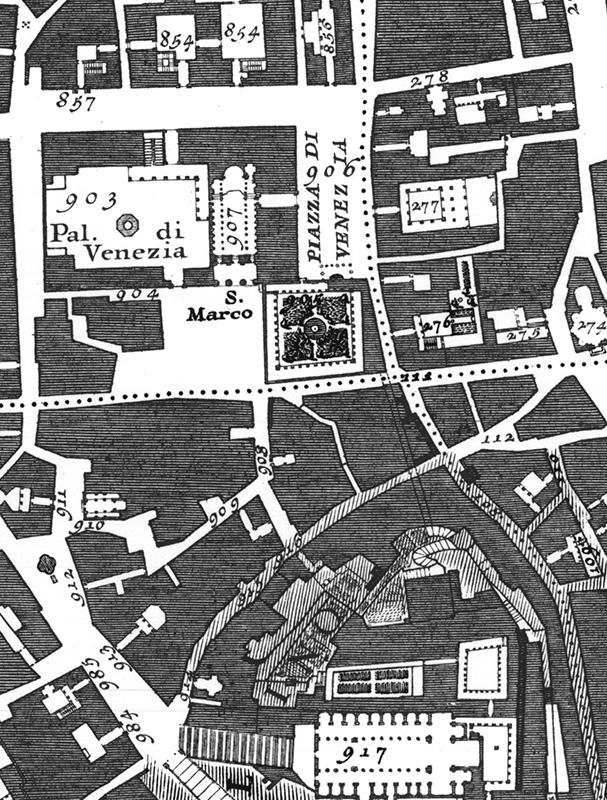

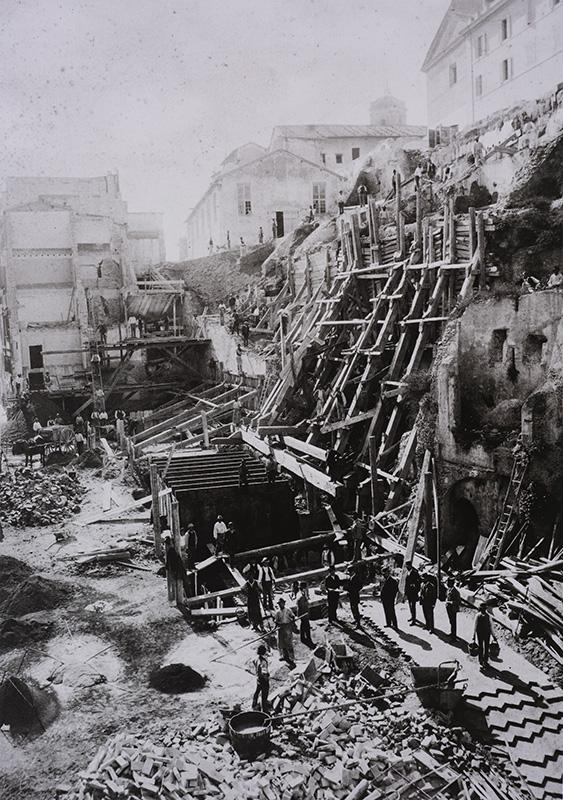

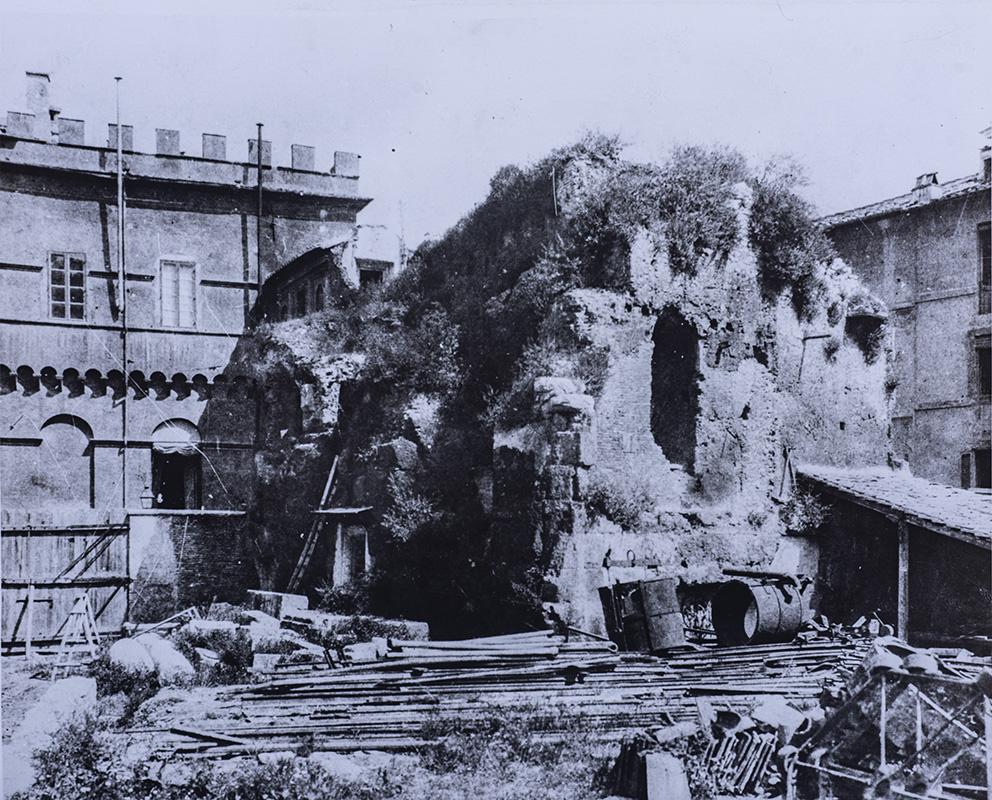

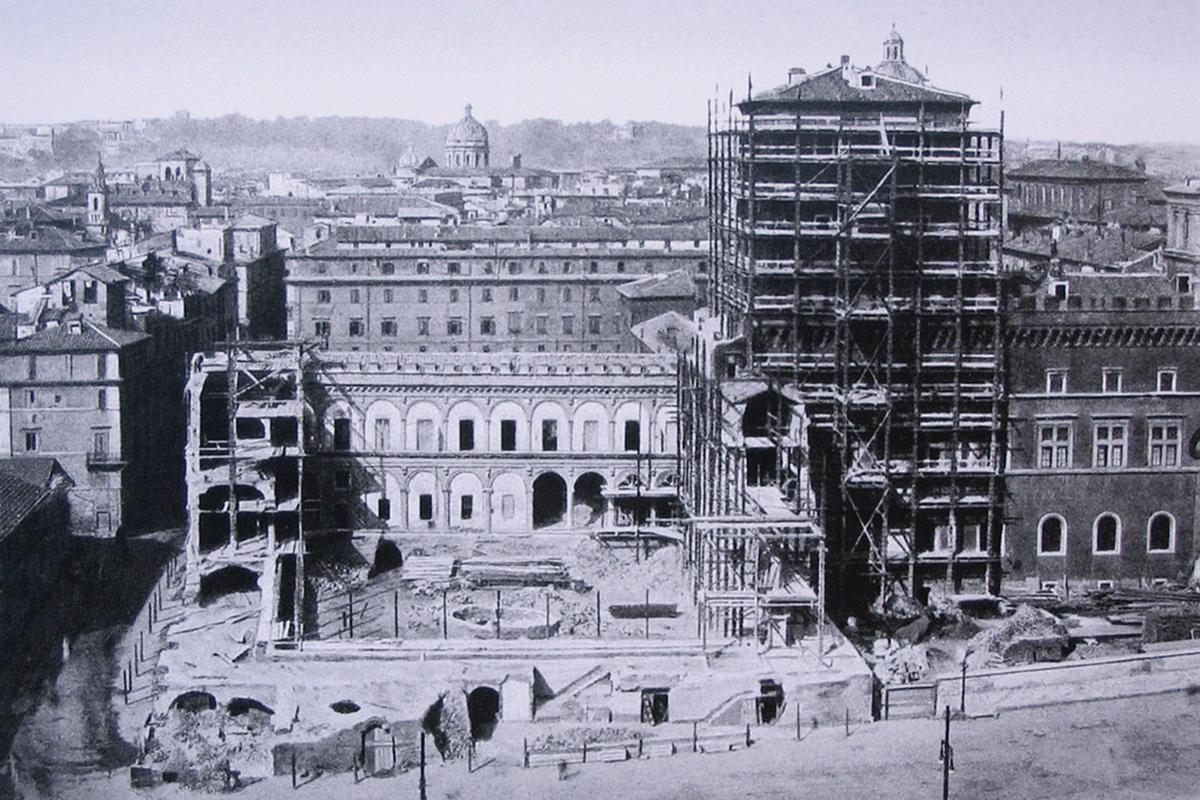

A phase of profound change began between 1884 and 1888. The palace became an important pawn in the redefinition of the area of Piazza Venezia, following the construction on the southern side of the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II, or Vittoriano, based on the project by Giuseppe Sacconi (1854-1905). Among other things, the demolition of two elements that from the mid-sixteenth century had characterised the building, projecting it in the direction of the Capitol, that is the Tower of Paul III and the relative overhead corridor connecting it to the Palazzetto, dates back to that period.

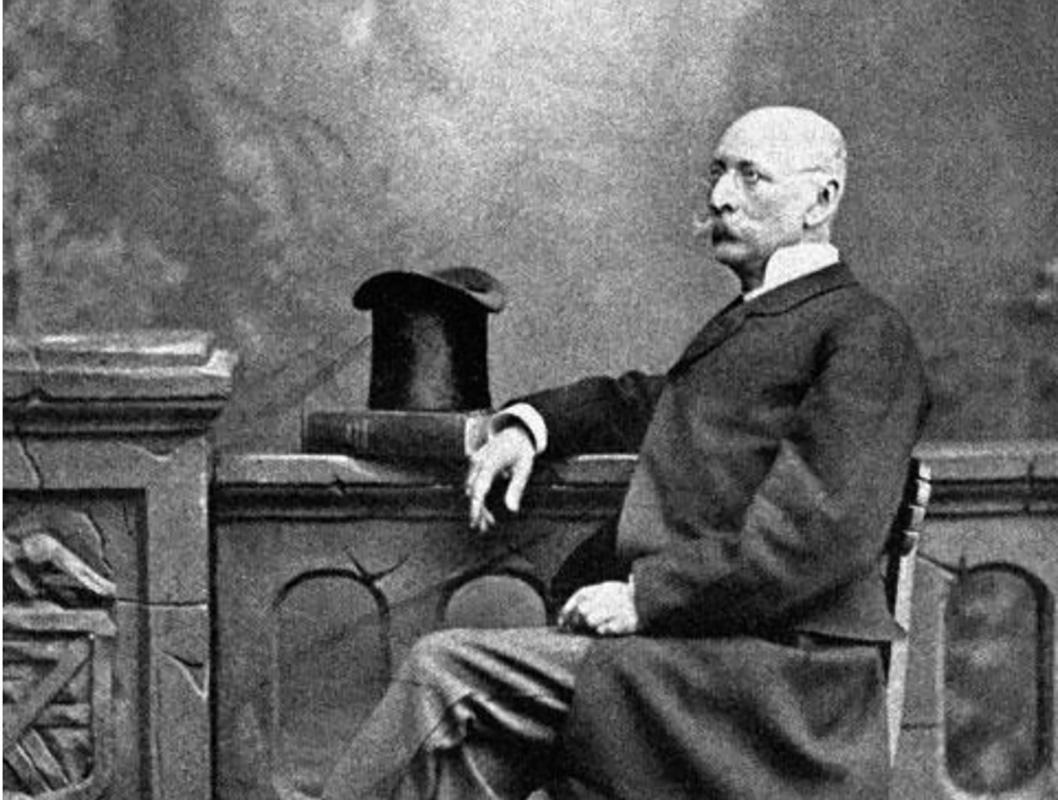

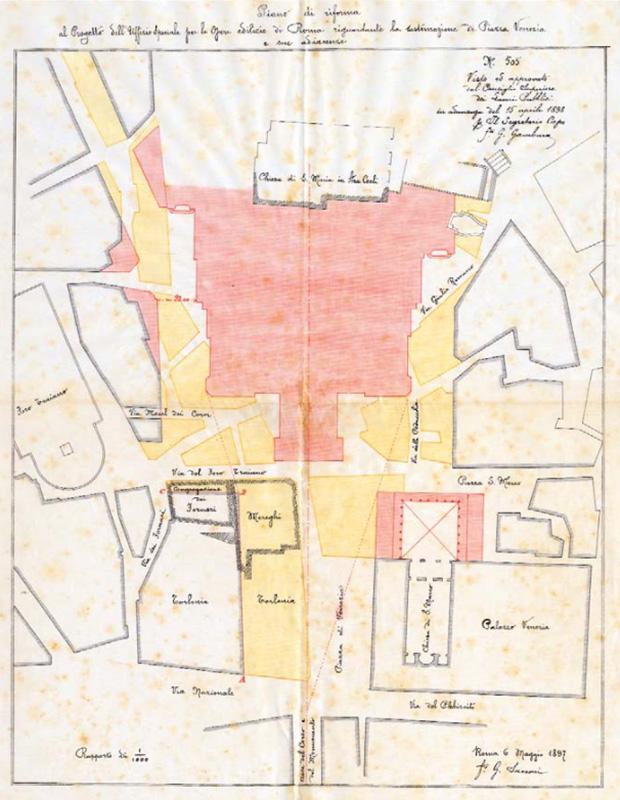

On 6th May 1897, Giuseppe Sacconi delivered a project aimed at completely redefining Piazza Venezia. The architect's objectives were essentially two, to regularise the layout of the square and to open up the view of the Vittoriano to those coming from the north, along the final stretch of Via del Corso. The fate of the Palazzetto was at that point sealed. According to Sacconi's idea, the building had to be moved right in front of the Basilica of San Marco, so as to transform it into a sort of atrium, or a four-sided portico entrance. Austria, which owned the building, however, raised a series of objections: a stalemate emerged, destined to last for over ten years.

The question of the Palazzetto was resolved on 23rd June 1908, when the Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni and the Austrian Ambassador Heinrich von Lützow settled it through a special agreement. According to the agreement, the work would be carried out at the expense of Austria, which also for this reason reserved the right to change Sacconi's project. On the advice of architect Ludwig Baumann (1853-1936), at the end of the demolition, the Palazzetto was completely rebuilt in a position further back, following the line of the western side of Palazzo Venezia, along via degli Astalli.