The victory of Angelo Zanelli

Thanks to a plebiscite, a young artist from Brescia managed to beat the other twenty-five far more well-known colleagues

Twenty-six artists took part in the competition for the decoration of the future Altar of the Fatherland, all strictly Italian as per the competition announcement. In some circumstances, think of Lodovico Pogliaghi (1857-1950) or Ettore Ximenes (1855-1926), they were already famous artists, accustomed to public tenders and selection mechanisms and, moreover, already operating at the Vittoriano. On this basis, Ximenes presented three sketches, one for each of the themes proposed in the announcement. In December 1908, the building of the Royal Carabinieri, on Lungotevere Flaminio, hosted the exhibition of the twenty-eight sketches, including the three by Ximenes.

In January 1909 the Royal Commission for the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II, chaired by the Minister of Public Works Pietro Bertolini (1859-1920), met to decree the winner. It was assisted by the artistic subcommittee, headed by Senator Gaspare Finali (1829-1914) and consisted of some famous architects and sculptors, from Ernesto Basile (1852-1932), Cesare Maccari (1840-1919), Gaetano Koch, Manfredo Manfredi and Pio Piacentini to Domenico Trentacoste (1859-1933). After selecting the sketches by Angelo Zanelli (1879-1942), Arturo Dazzi (1881-1906), Antonio Ugo (1870-1950) and of Pogliaghi himself, the subcommittee unanimously expressed itself in favour of the first.

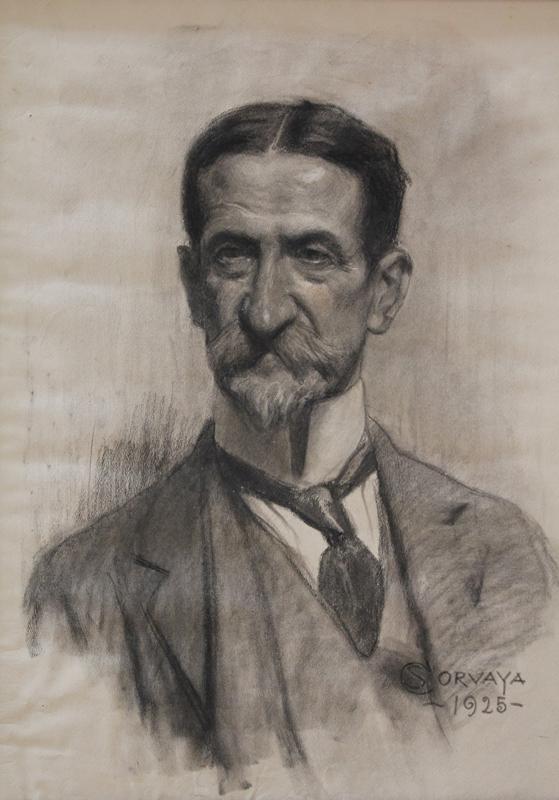

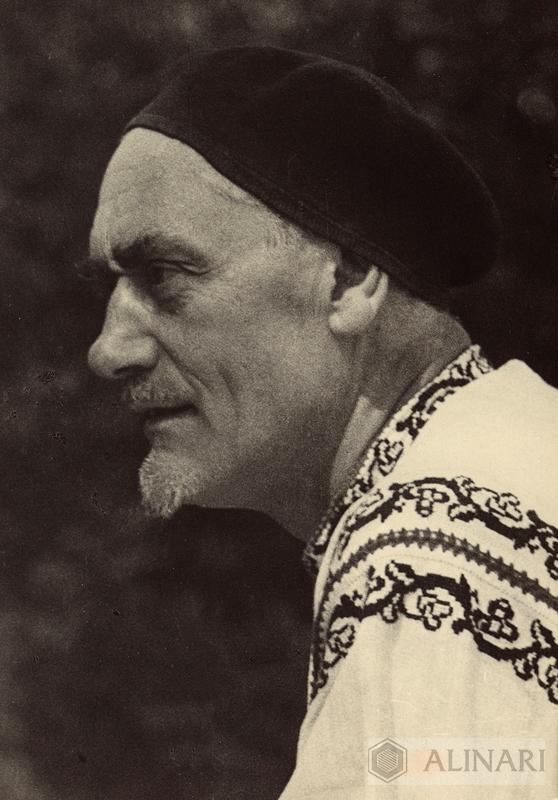

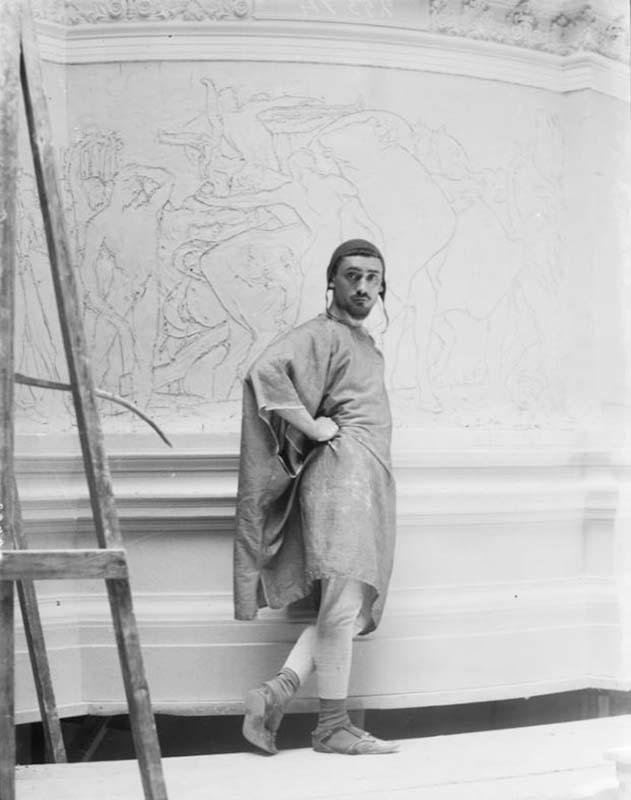

When Angelo Zanelli (1879-1942) took part in the competition he was about thirty years old. Originally from the province of Brescia, Zanelli was trained in Florence, at the Academy of Fine Arts, where he had attended the lessons of Augusto Rivalta (1837-1925). Academic accommodation allowed him to move to Rome in 1903, which then became his permanent residence and where his academic style evolved in a Liberty and Symbolist direction.

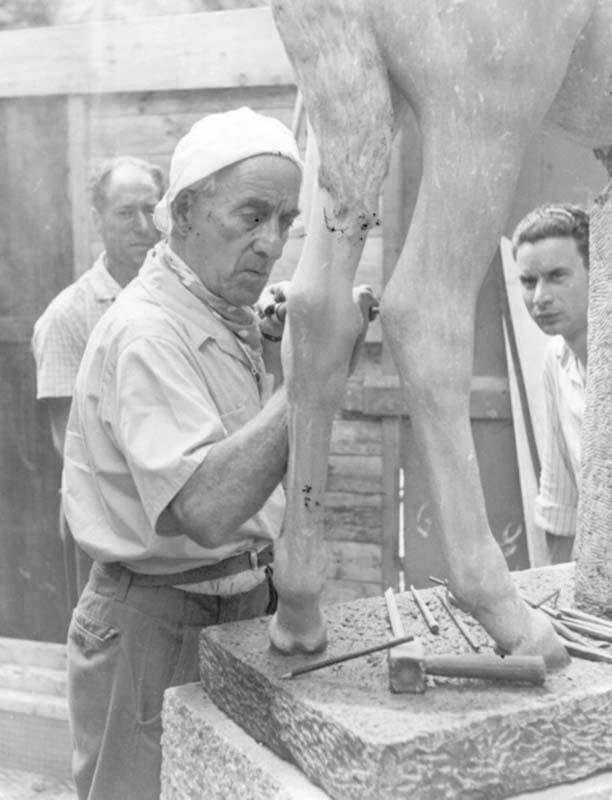

His first success was in 1906, the year of the Monument to the minister Giuseppe Zanardelli, installed on the lakeside of Salò. The victory of the competition for the Vittoriano launched him into the Olympus of the greats: after that Zanelli obtained commissions of great prominence, from the Mausoleum of General José Gervasio Artigas in Montevideo to the group of monumental sculptures for the Capitol de Havana in Cuba, including the Statue of the Republic.

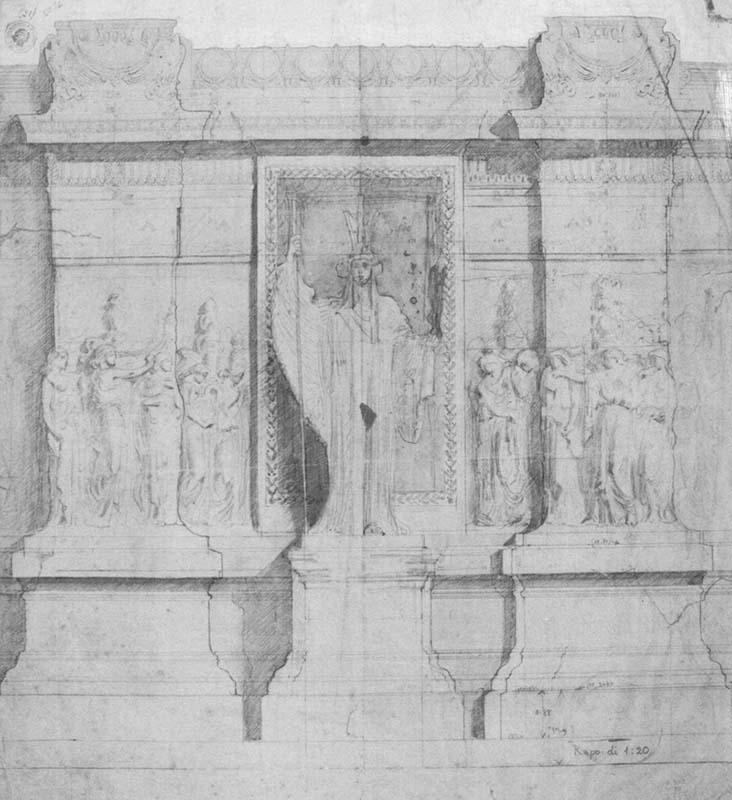

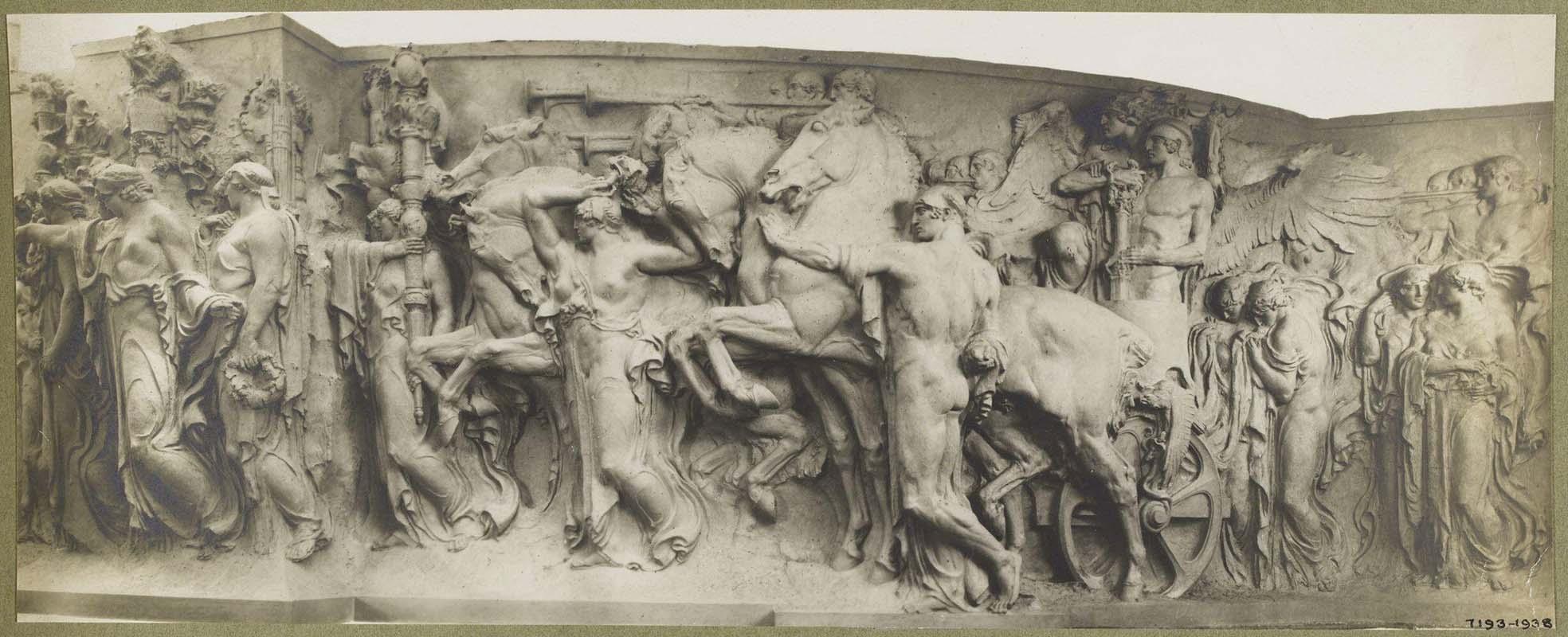

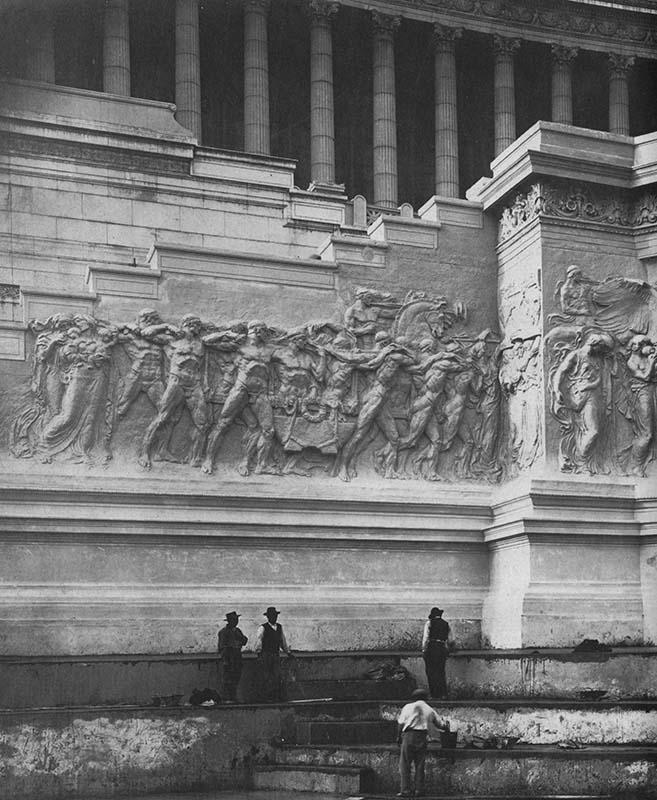

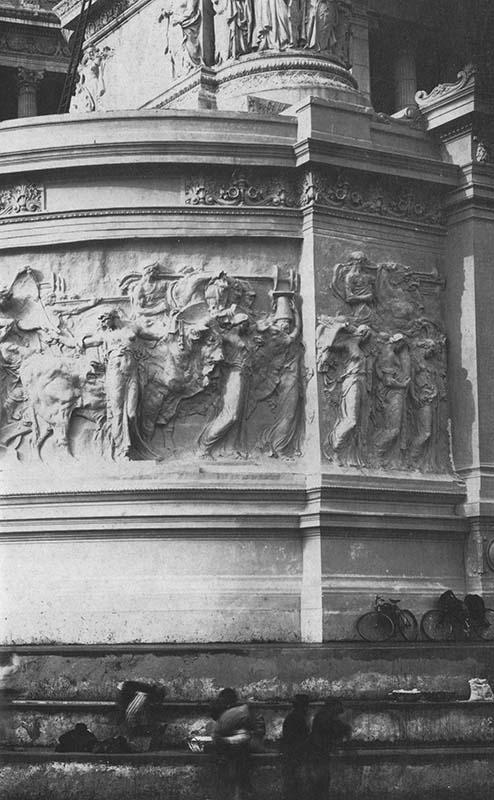

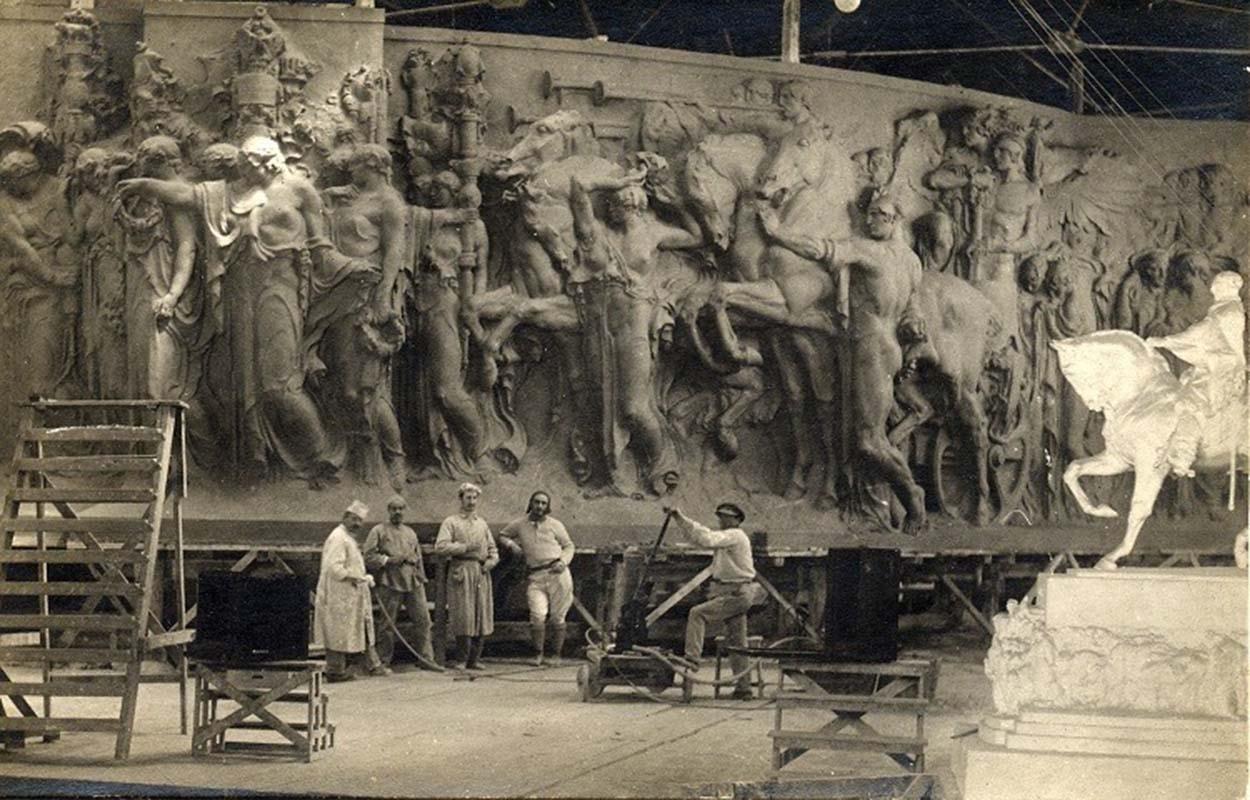

Of the three themes proposed in the competition announcement, Zanelli chose the last one, the one that allowed him the greatest freedom. At the sides of The Goddess Rome, the artist represented on the right The love of country that fights and wins, a long procession made up of figures of mythological and pagan origin; on the left The work that builds and fecundates, a second procession where agricultural activities alternate with industrial ones.

Zanelli here reports a reference to the Roman triumphs of the classical age, in particular to the two reliefs inside the Arch of Titus, but reread and filtered through a modern lexicon, indebted to the symbolist matrix of Leonardo Bistolfi. In The Goddess Rome, which was a few years later, the artist would modulate this basic style and assume interpretations close to the Vienna Secession and to the art of Gustav Klimt.

Unlike the artistic subcommittee, the Royal Commission did not agree on the name of Angelo Zanelli: three members - sculptor Giulio Monteverde (1837-1917), architect Alfredo d'Andrade (1839-1915) and art historian Corrado Ricci (1858-1934), at the time general director of Antiquities and Fine Arts - preferred to abstain. Thus the two bodies in charge of directing the work of the Vittoriano came into conflict.

To settle the question, it was established that the two most appreciated artists, Zanelli and Arturo Dazzi, should develop their sketches to life-size and deliver them on 10th November 1910, to exhibit them in turn to the public in 1911, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Unification of Italy. The final decision would be up to the public.

As in many other circumstances in the long journey of the history of Italian art, the spokespersons of two different styles challenged each other in a sort of duel: on the one hand here is Dazzi, spokesman for the historicist-realist current, on the other Zanelli, champion of symbolism.

At that point, both Dazzi and Zanelli only had a few months to transform their respective sketches, less than 50 centimetres high, into life-size models of about three metres. Zanelli succeeded in doing this by making use of a team of collaborators and a machine made up of a system of graduated set squares, called a pantograph. This system, the result of the working methods characteristic of the industrial revolution and known for some time in France, allowed him to deliver the definitive model in five months, from July to 30th November 1910.

On 4 June 1911, on the occasion of the ceremony for the fiftieth anniversary of the Unification of Italy, Zanelli and Dazzi competed for the winner's prize. The first model set up belonged to Zanelli; after a couple of weeks it was the turn of Dazzi. The competition, recalls the art historian Rossana Bossaglia, sparked the passions of public opinion in the same way as a sports event, thanks also to the press.

After a few months the judgment swung in favour of Zanelli, in the footsteps of what had already emerged within the artistic subcommittee of the Vittoriano. On this basis, on 1st December 1911 the Royal Commission unanimously decreed the victory of the sculptor from Brescia.