A stage for the regime, its rites and its protagonists, during the final war years, the Vittoriano protected the civil population of Rome in its basement

The fascist regime (1922-1943) appropriated the Vittoriano, fully grasping its architectural, artistic and scenography qualities, but transforming it into a cog in its rhetoric and propaganda machine. From a symbol of unity and liberty, the monument was reduced to being the backdrop for the military parades that took place along the via dell’Impero, today’s via dei Fori Imperiali, and for the speeches given by Benito Mussolini from the balcony of Palazzo Venezia.

A crowd waits for Mussolini to pass before the Vittoriano during the military parade in Via dell’Impero (now Via dei Fori Imperiali) held to mark the 10th anniversary of Italian Fascism

Military parade in Piazza Venezia, circa 1930

In 1924, architect Armando Brasini (1879-1965) took on the position of artistic director of the Vittoriano, which he would maintain until 1939. Brasini, trained as a plasterer at the Institute of Fine Arts and at the school of the Industrial Art Museum, managed to establish himself as an architect already during the 1910’s.

Portrait of architect Armando Brasini

His language, initially Liberty, had taken on a magniloquent and retrospective development after the war, that is, mainly directed towards the past, particularly to the Renaissance and the Baroque: this application is evident in the exhibition of the works recovered from Austria, set up in Palazzo Venezia in 1922 and in the project for the Basilica of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Piazza Euclide, Rome.

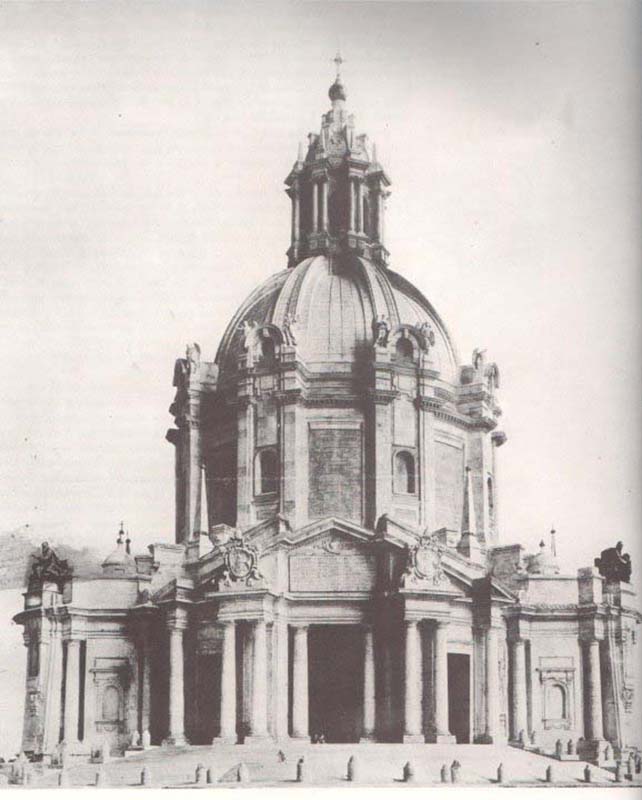

Design for the Basilica of Sacro Cuore Immacolato di Maria by Armando Brasini, 1923: the dome was never built, unlike the architect's plan

Plaster half-model of the dome (never completed) for the church of Sant’Ignazio di Loyola in the Field of Mars, Rome, by Armando Brasini, 1921

Inside the Vittoriano, Brasini worked on two different styles. For the decorative and sculptural apparatus, the architect suggested minimal works, in fact limiting himself to finishing the works already set up previously. On 21st April 1925, the birth date of Rome, the inauguration of the statue depicting the Goddess Rome placed in the centre of the Altar of the Fatherland took place. In 1927 it was the turn of the Quadrigae of Liberty and Unity, placed on top of the Monument, over a hundred metres up.

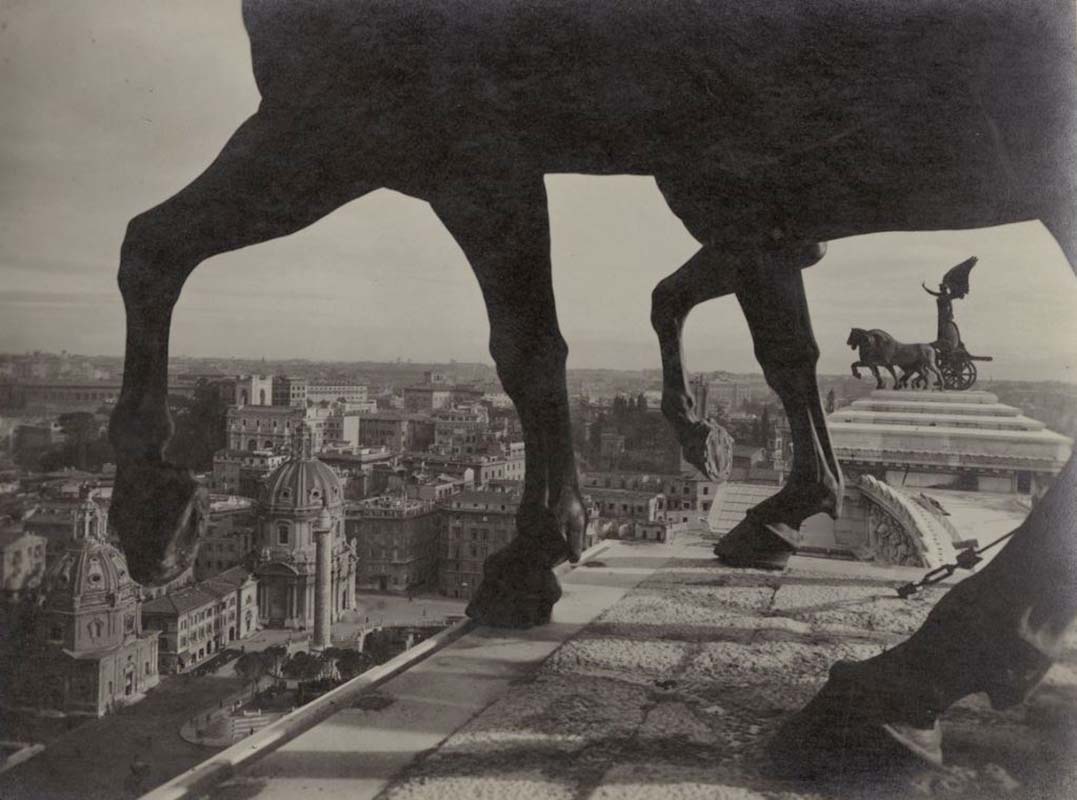

Panorama from the Quadriga of Liberty on the western propylaeum of the Vittoriano, late 1940s

Brasini's mark, on the other hand, went further for the architecture. The arrangement of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and, within the complex, the relative Sacellum and the setup of the Shrine of the Flags, can be ascribed to his drawings. Along the eastern side of the Monument, enhanced by the contextual construction of via dell' Impero, he developed a previous project by Manfredo Manfredi and Pio Piacentini, once a series of various problems had been solved, he built today's Imperial Forums’ Wing.

The Imperial Fora during demolition and construction. In the background, the eastern side of the Vittoriano (the Brasini wing) and the convent of Aracoeli, also under construction, in a photograph taken 23 September 1932

The Vittoriano from Via dei Fori Imperiali in the late 1930s

The Vittoriano also played a notable role in the final stages of the Second World War. Once the curtain had fallen on the triumphs of the regime and on the military parades, Rome was forced to face the threat of Allied bombing. The basement of the Monument then took on the function of an air-raid shelter. At the sound of the sirens, hundreds got used to running through its access doors, feeling protected by the rock above and by the very bulk of the building.

Entrance to an air raid shelter in Rome

On 4 June 1944, the Allied troops of the American Army reached Piazza Venezia to liberate the first capital city in Europe from Nazi occupation

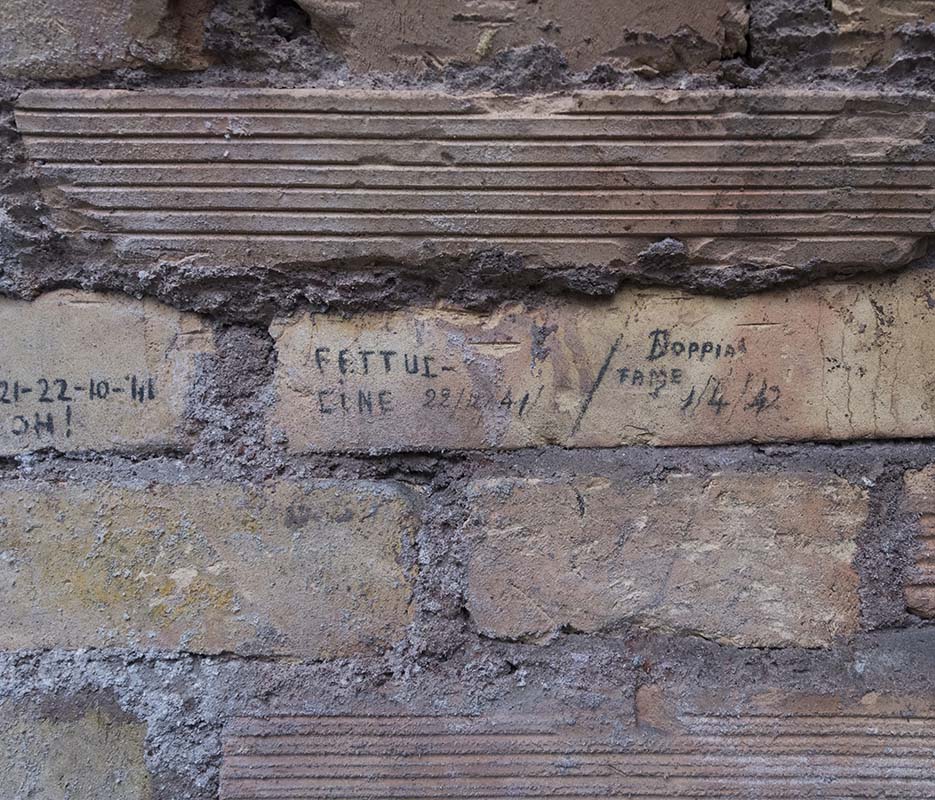

The shelter’s furnishings included rows of benches, a first aid post, the supply of drinking water, emergency exits and toilets. This dramatic phase can still be known today thanks to a series of original graffiti. "As hungry as a wolf”, "Twice as hungry" or "Fettuccine", are some of the epigraphs drawn by the citizens of Rome and found on the walls of the underground area.

Doppia Fame (double the hunger) and Fettuccine written in the underground areas of the Vittoriano