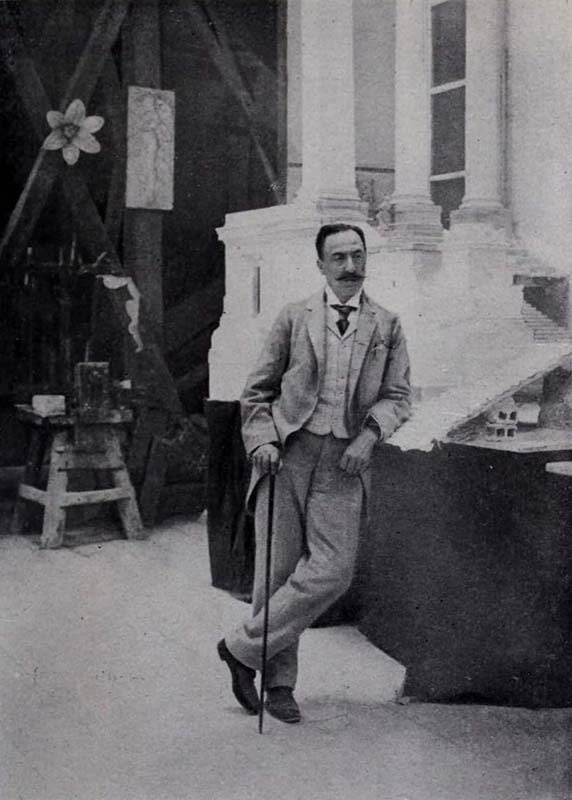

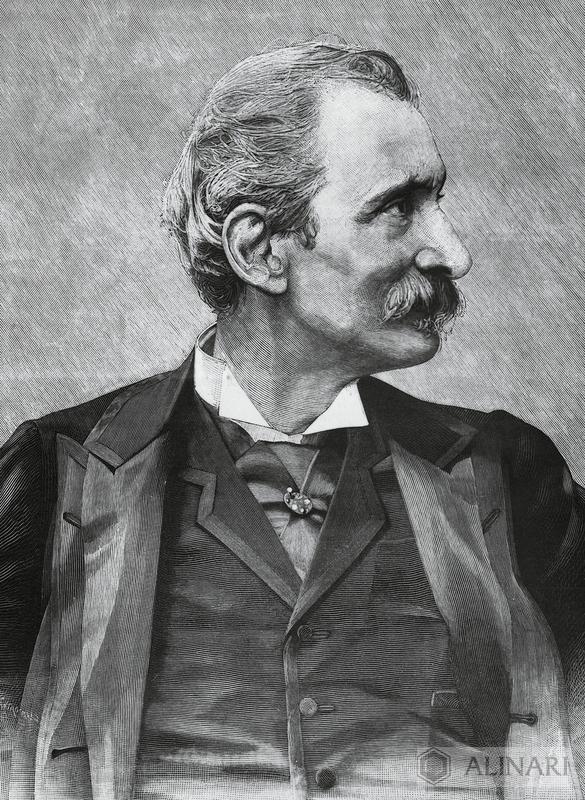

Giuseppe Sacconi was still quite young when he designed the Vittoriano, which clearly reflects the artistic merit and quality of this great artist.

Originally from Le Marche, Giuseppe Sacconi (1854-1905), had moved to Rome in 1874. Barely thirty, Sacconi won the second and decisive competition for the Vittoriano: his project was inspired by the classical and Renaissance tradition, particularly by the style of Donato Bramante.

Architect Giuseppe Sacconi posing in his studio, 1902

Commemorative medallion with a portrait of architect Giuseppe Sacconi (obverse) and the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II (reverse) minted in 1911

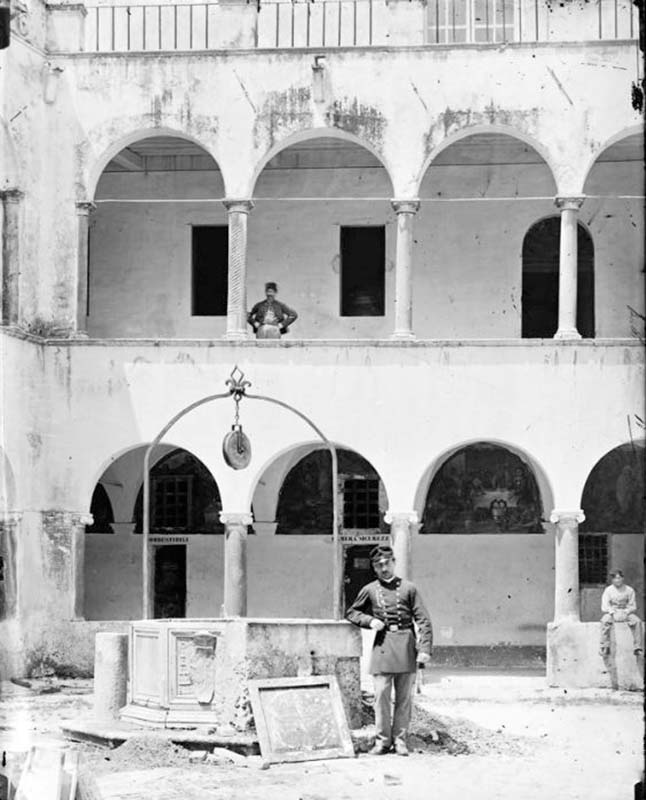

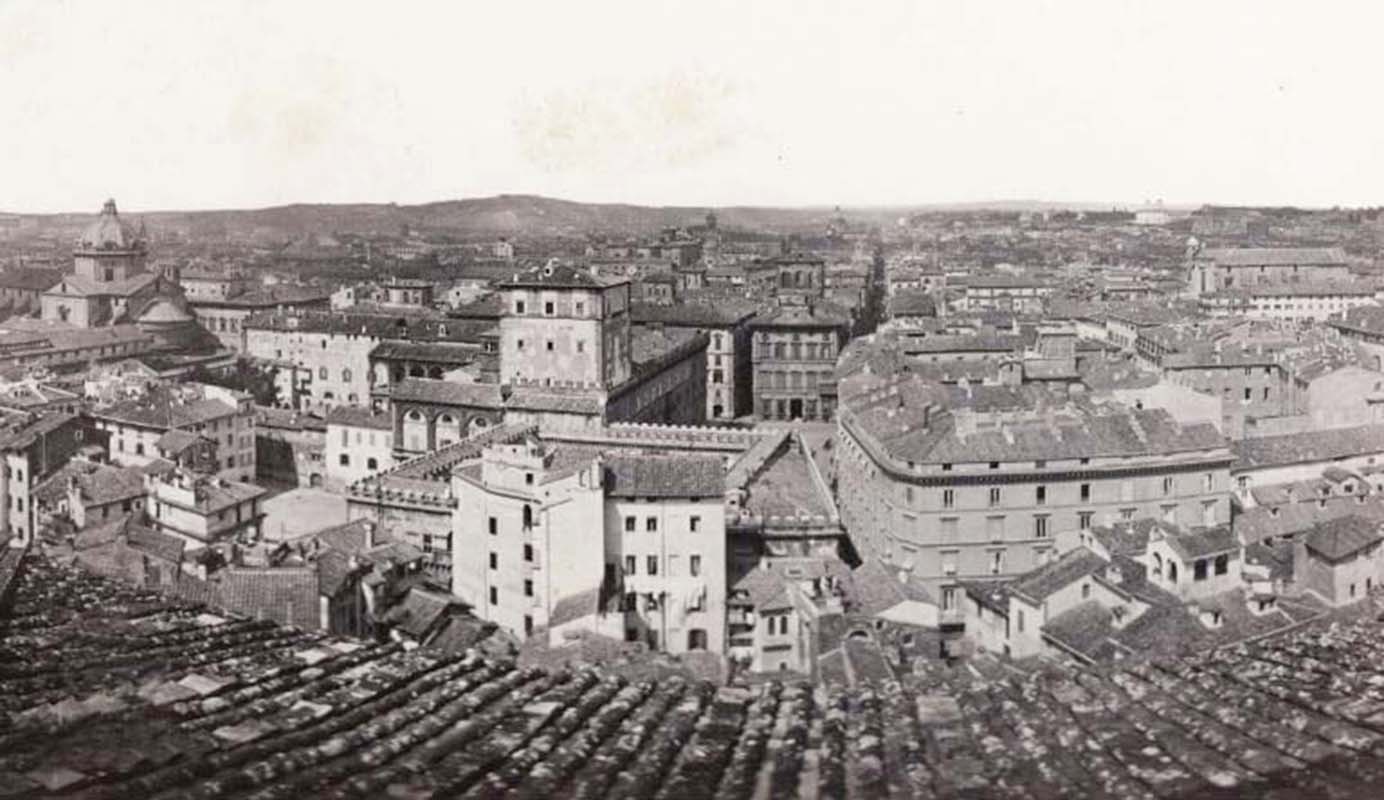

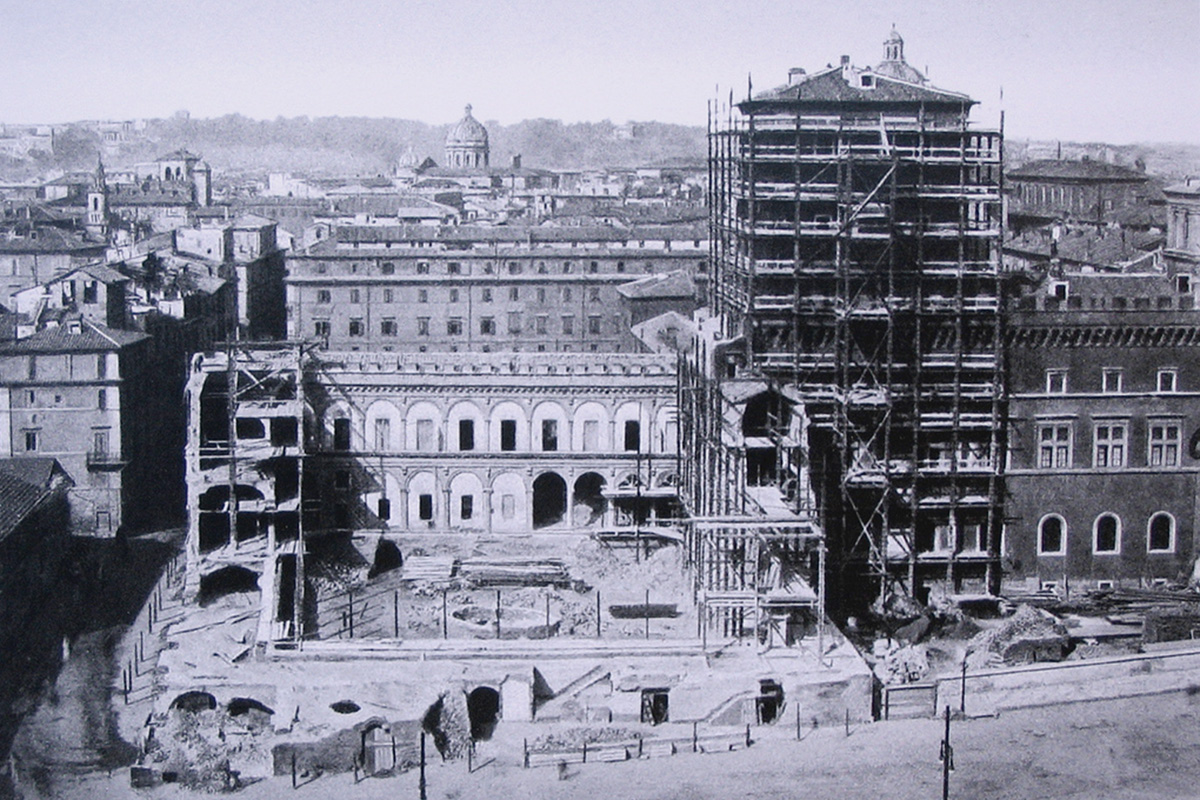

In order to build the Vittoriano, it was necessary to demolish a large number of buildings that were in the area. Thus the three medieval cloisters of the Aracoeli Convent, the so-called Tower of Paul III and the overpass or 'passetto' connecting it with Palazzo Venezia, known as the Arch of San Marco disappeared

The Convent of Santa Maria in Ara Coeli being demolished during refurbishment of the Piazza Venezia area on the occasion of construction of the Vittoriano in Rome

Torre di Paolo III [Tower of Paul III] at the Campidoglio in the process of being demolished during refurbishment of the Piazza Venezia area on the occasion of construction of the Vittoriano in Rome

A cloister of the Convent of Santa Maria in Ara Coeli (Saint Mary of the Altar of Heaven), demolished in 1886 to prepare the area that is now Piazza Venezia

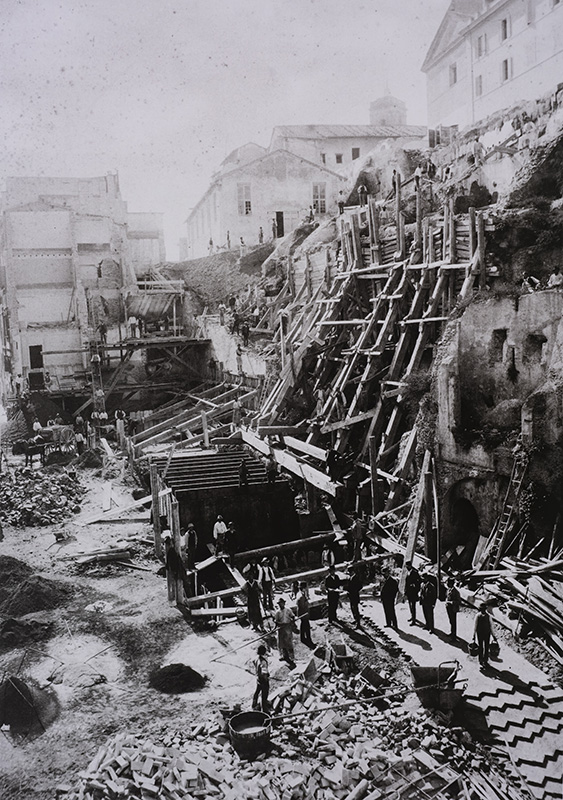

Demolition on the Capitoline Hill, circa 1885, when the work was being done on the area around Piazza Venezia

View of buildings in the Campidoglio area that were demolished during refurbishment of the Piazza Venezia area on the occasion of construction of the Vittoriano in Rome. In the background, Torre delle Milizie

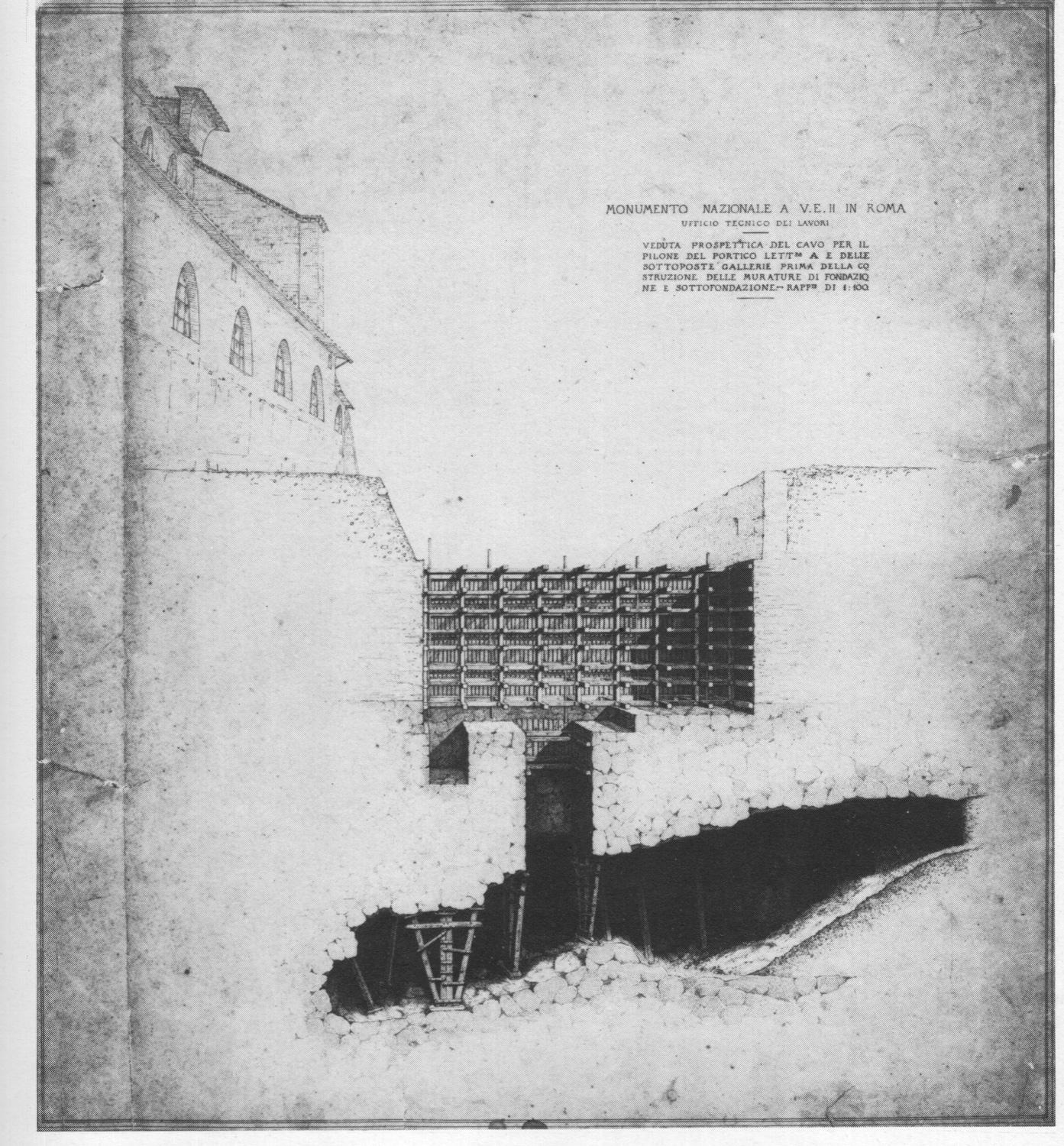

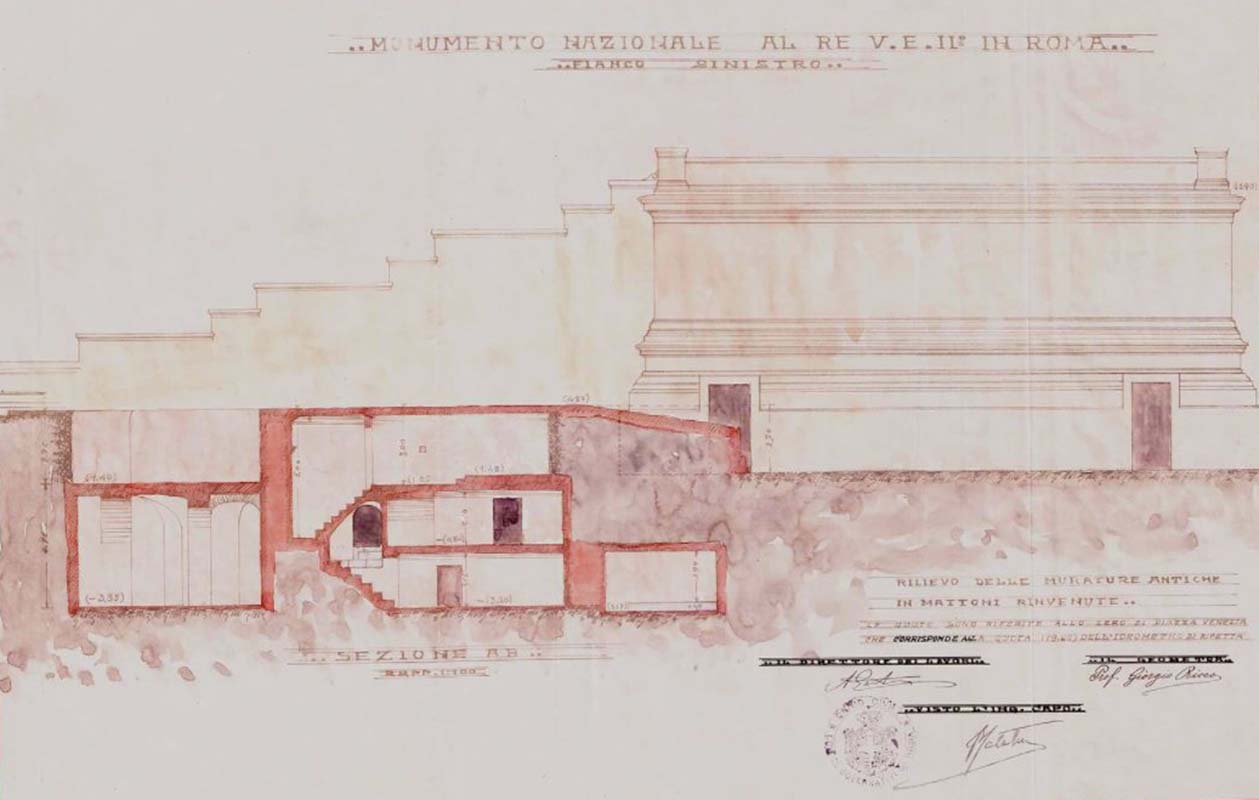

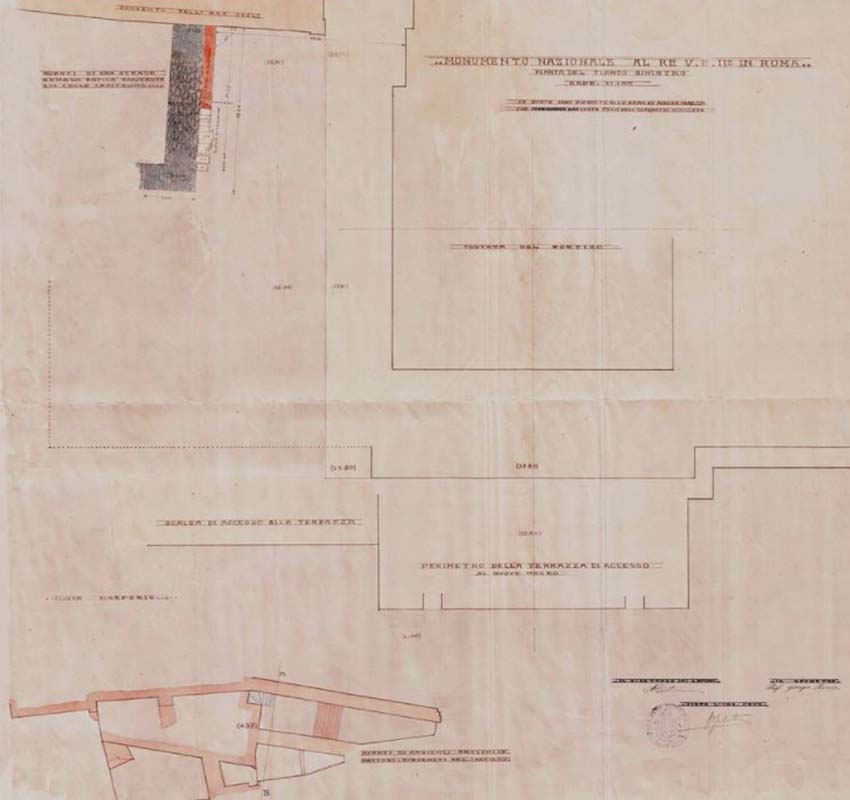

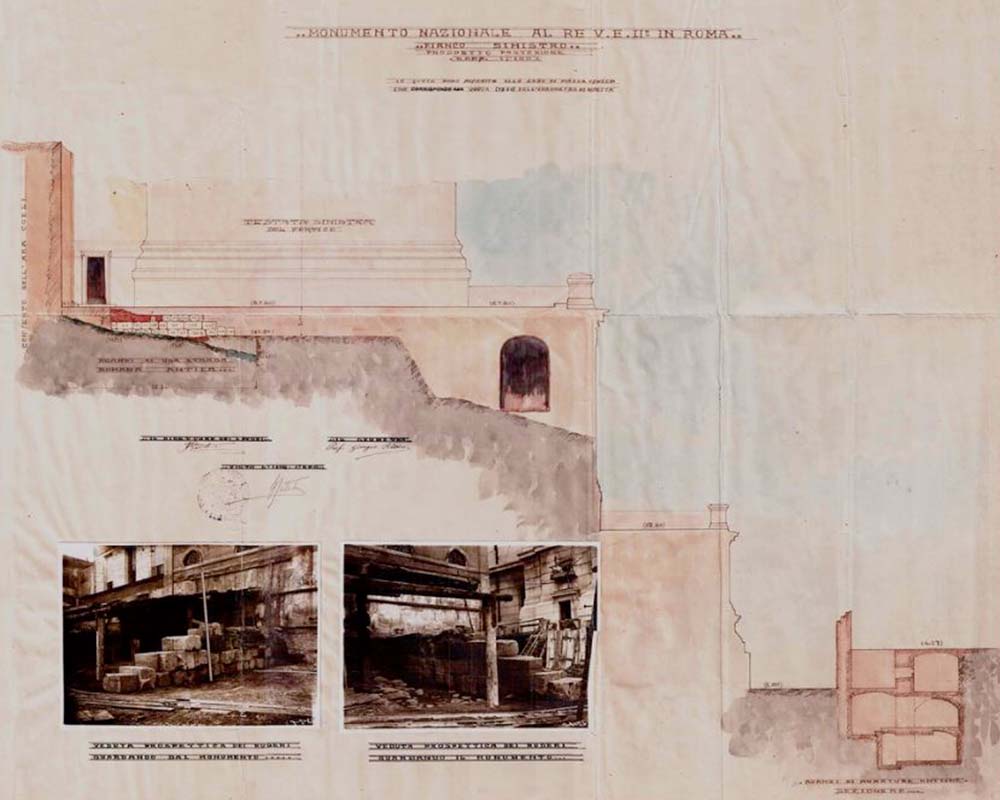

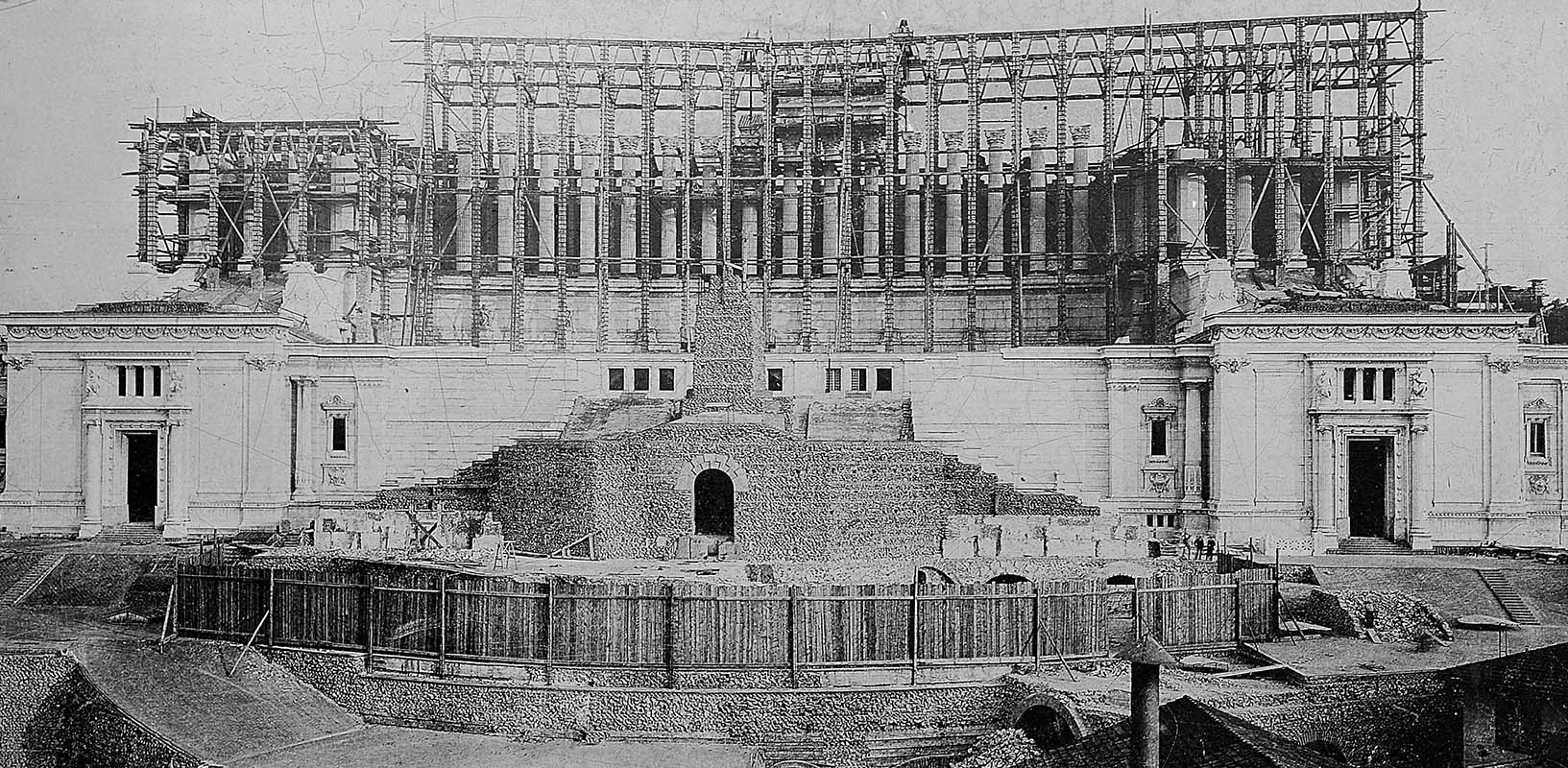

On 22nd March 1885, the ceremony for laying the first stone of the monument took place. The construction site soon encountered a series of considerable difficulties, connected to the instability of the foundation ground and to the discovery of some important finds, including a section of the Servian Walls, dating back to the sixth century BC: a profound overhaul of the original project was thus necessary.

Laying of the first stone of the Vittoriano 22nd March 1885

Geological difficulties faced by Sacconi, perspective view with excavation of the pillar and its foundations

Servian walls discovered during the excavation works for the Vittoriano

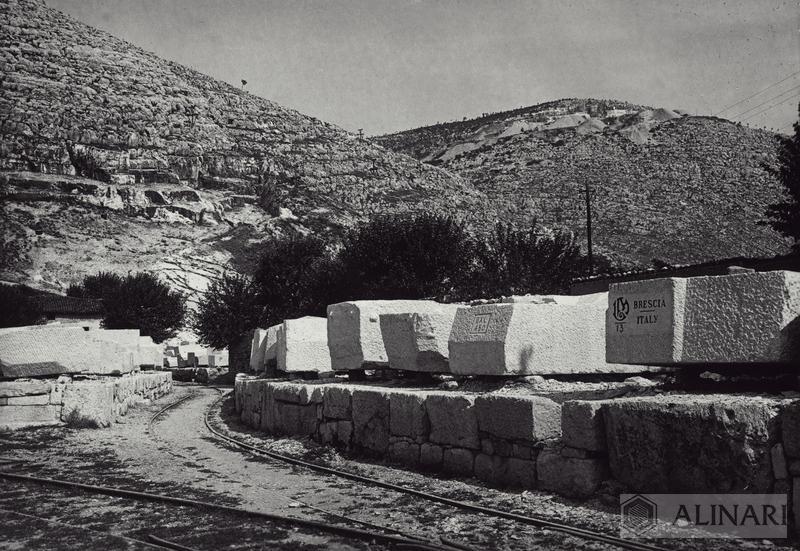

Sacconi had initially thought of travertine, which was characteristic of many Roman buildings. In the end, however, Botticino marble was chosen, perhaps at the suggestion or imposition of the powerful minister Giuseppe Zanardelli (1826-1923). This material, which originates from quarries located near some towns close to Brescia, including Botticino, is known for its compactness and pure white colour.

Portrait of the Minister of Public Works Giuseppe Zanardelli

Botticino (Brescia), stone blocks worked in the quarry ready for transport

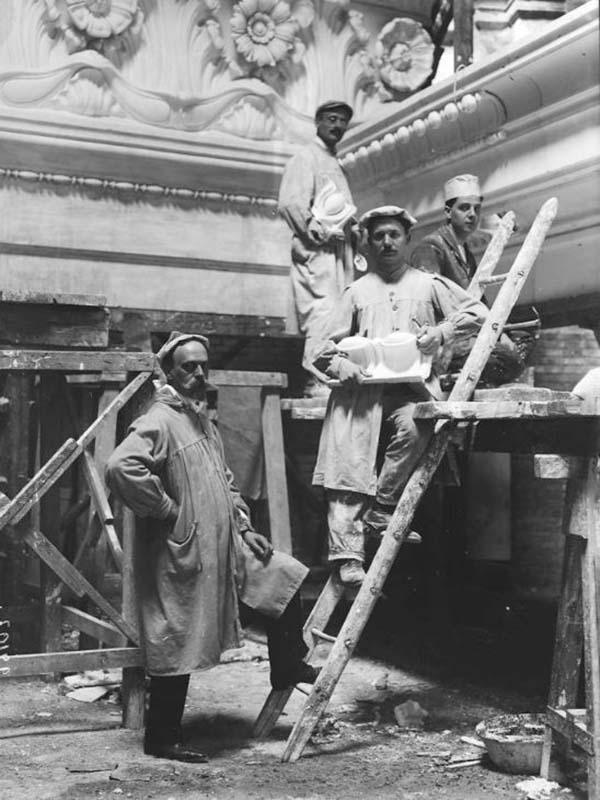

Giuseppe Sacconi deeply believed in the unity of architecture and sculpture. He paid great attention to the choice of subjects and to that of the artists, providing them with drawings and even indications on the construction site. Under the direction of Sacconi, a large part of the architectural sculptures and the four sculptures at the top of the Doors were thus carried out, depicting The Politics, The Philosophy, The Revolution and The War.

A group of artists posing while working on the sculptural and architectural decorations of the Vittoriano in a photograph by Mario Nunes Vais, 1906

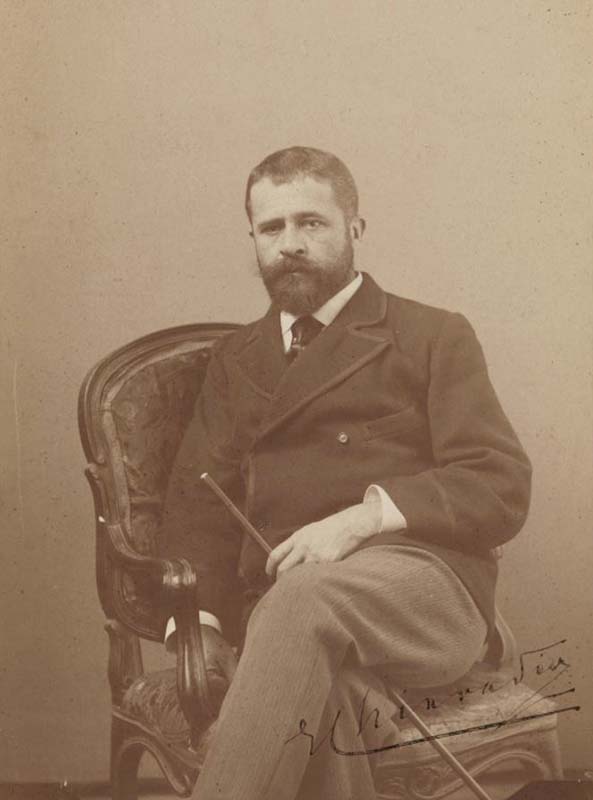

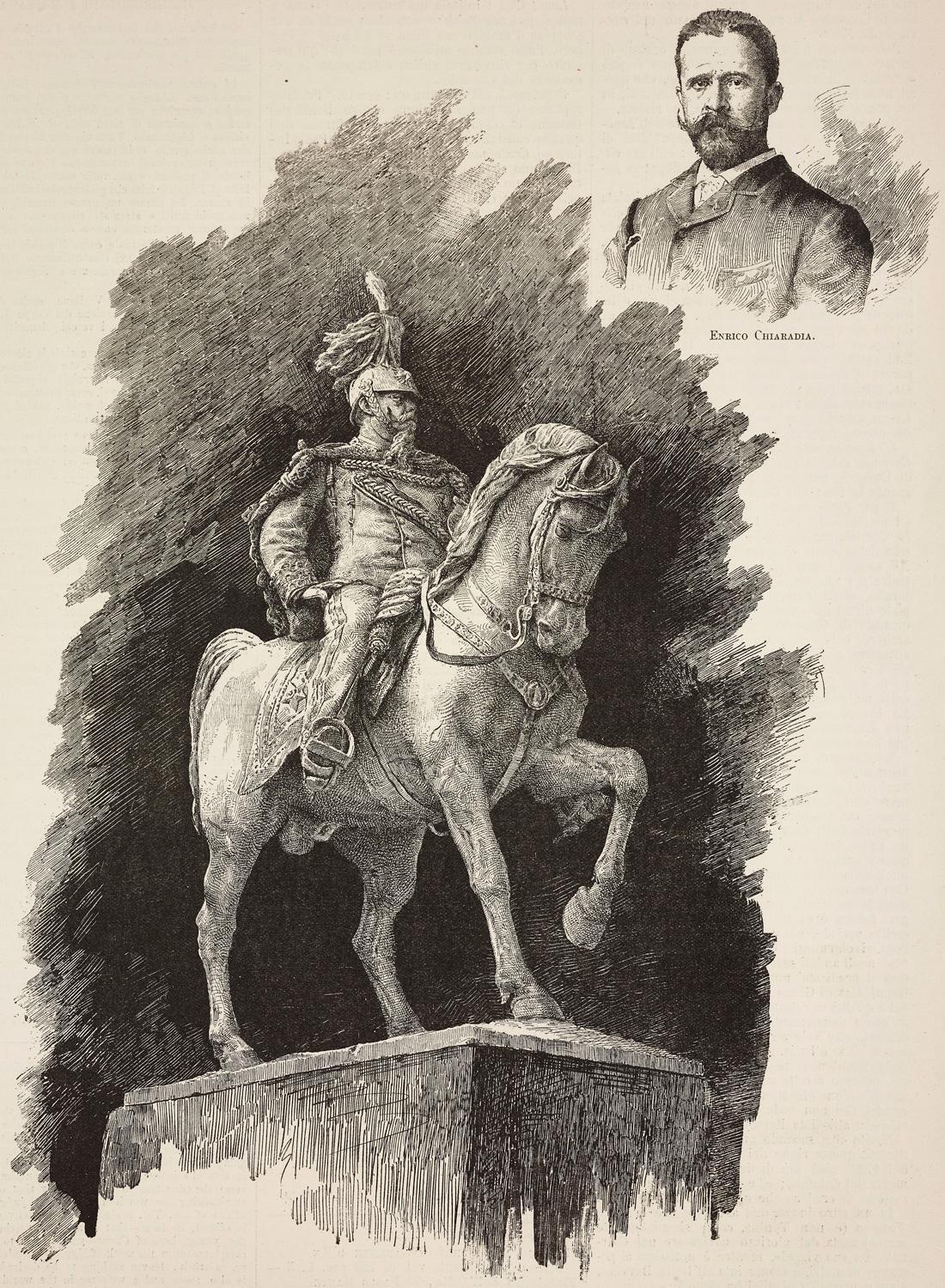

In 1884, in open contrast to Sacconi's will, the Royal Commission appointed by the Government to supervise the work of the Vittoriano, separated the statue of the King from the overall construction site, for which it launched a special competition. After a series of vicissitudes, in 1889 the victory went to the Friulian sculptor Enrico Chiaradia (1851-1901).

Portrait of sculptor Enrico Chiaradia

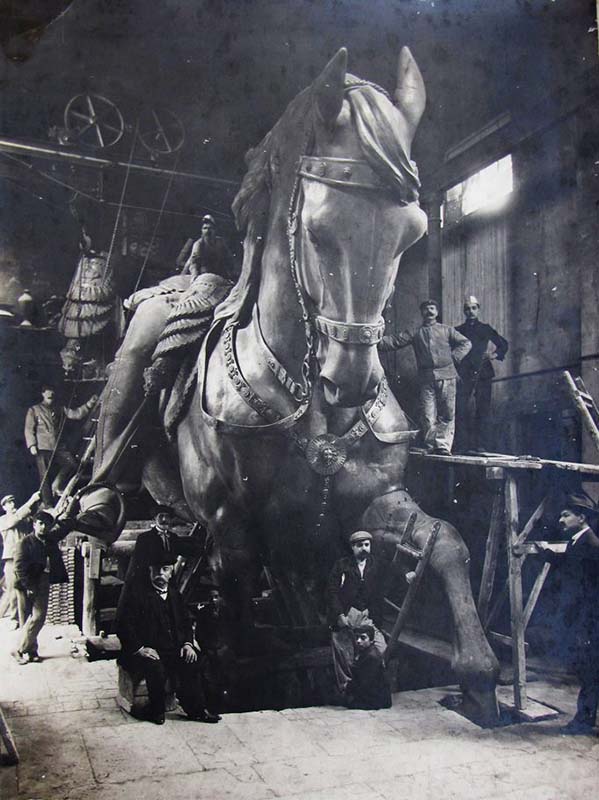

The equestrian statue of Victor Emmanuel II in the workshop of Fonderia Bastianelli as it was being made and assembled

Giovanni Bastianelli, owner of the foundry, and a group of workers in the belly of the horse of the equestrian monument of Victor Emmanuel II on 5 February 1911

Group of men photographed in the belly of the horse of the equestrian monument of Victor Emmanuel II

Sacconi, who was already hostile to the idea of separating the statue of the King from the overall construction site, thus losing control, declared himself against the outcome of the competition: Chiaradia's realistic style was in his opinion incompatible with the classicist and Neo-Renaissance structure of the Vittoriano. After Chiaradia died in 1901, the statue of the king on horseback was finished by the Florentine sculptor Emilio Gallori (1846-1924).

The equestrian group of the statue of Victor Emmanuel II divided in two parts being transported on the streets of Rome (Palazzo Venezia is in the background), 1910

Two workers pose on the bust of the equestrian group of the statue of Victor Emmanuel II in the work yard of the Vittoriano

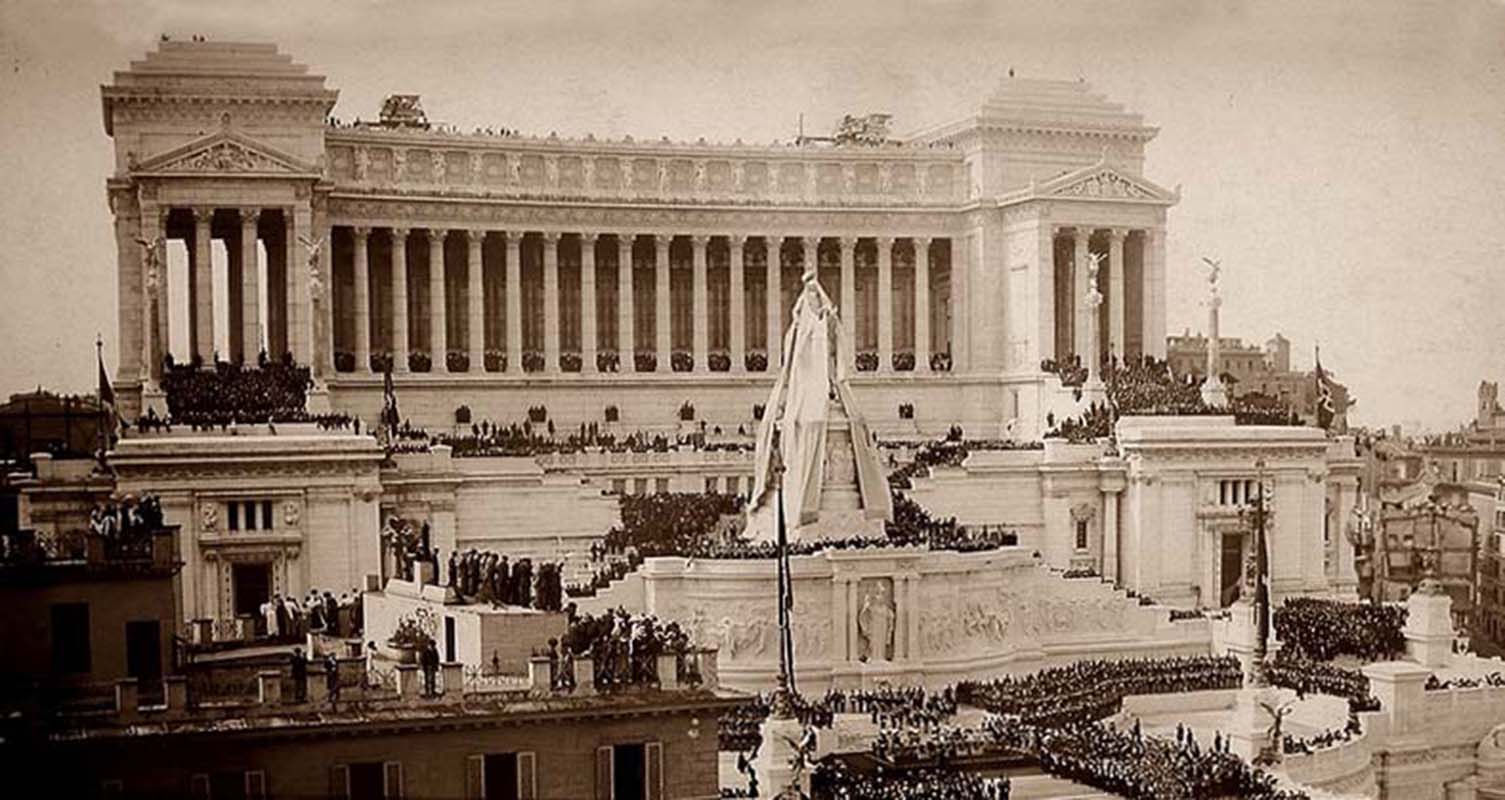

Inauguration of the Altar of the Fatherland on 4 June 1911, detail of the Equestrian Statue of Victor Emmanuel II just before being revealed

Piazza Venezia with the Equestrian Statue of Victor Emmanuel II, as seen from the terrace of Piazzale del Bollettino of the Vittoriano, 1935

Equestrian Statue of Victor Emmanuel II, 1950s

In 1890, on the occasion of the visit of Umberto I (1878-1900) to the construction site, Sacconi de facto presented a new project, which took into account the need to consolidate the grounds and to preserve the "Walls of the Kings", that is to say a stretch of the Servian walls dating back to the 6th century BC.

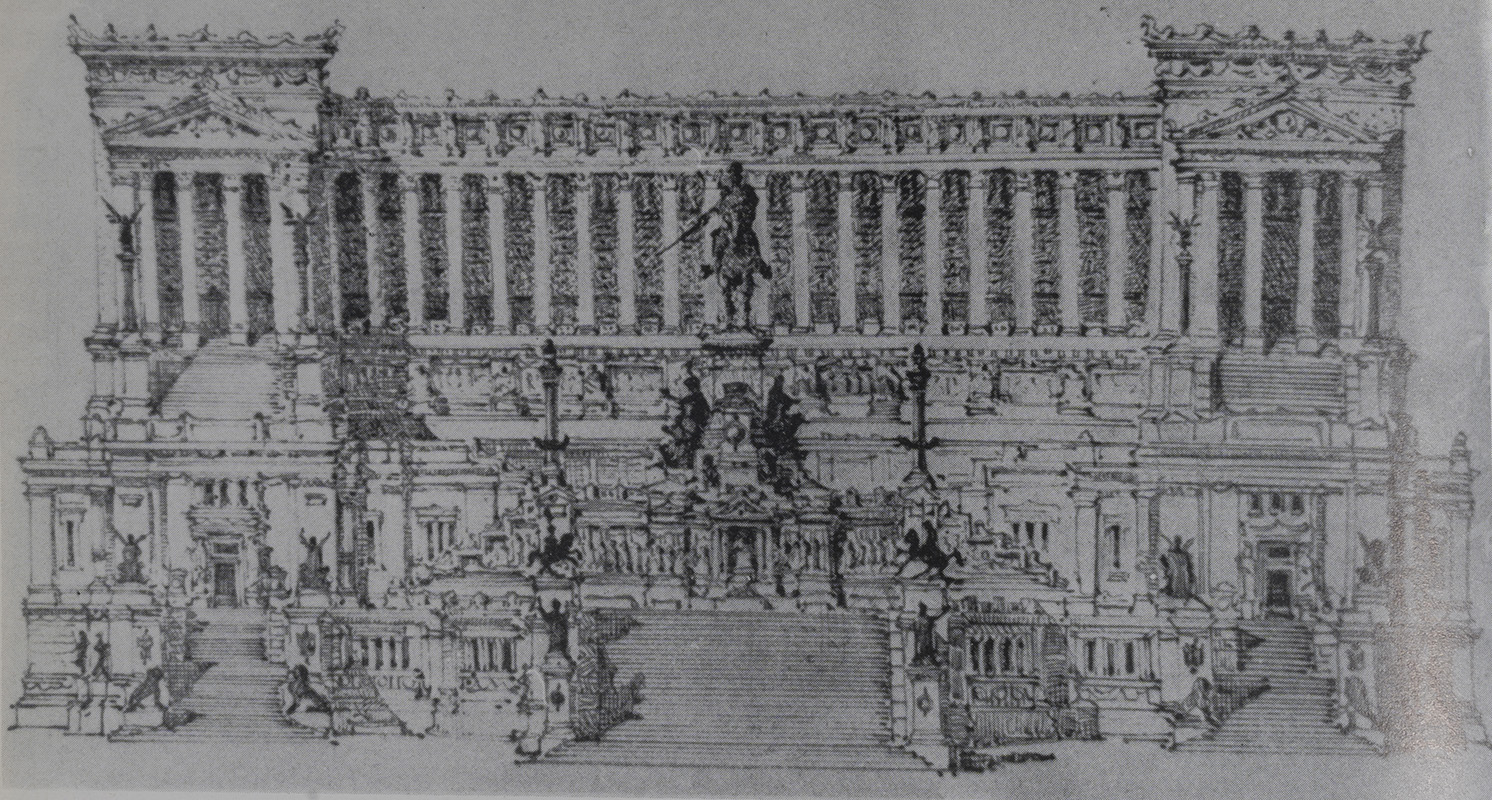

The second design for the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II created by Giuseppe Sacconi in preparation for King Umberto I's visit to the work yard in June 1890

The architect first of all envisaged massive substructures to keep the building standing: this would create large interior spaces ideal for housing museums: of the Crowns on the ground floor, of the Risorgimento and of the Shrine of the Flags. He also enlarged the monumental portico from 90 to 114 metres. This type of modifications had a considerable impact on the costs of the structure, which rose from the 9 million lire expected to 26.5.

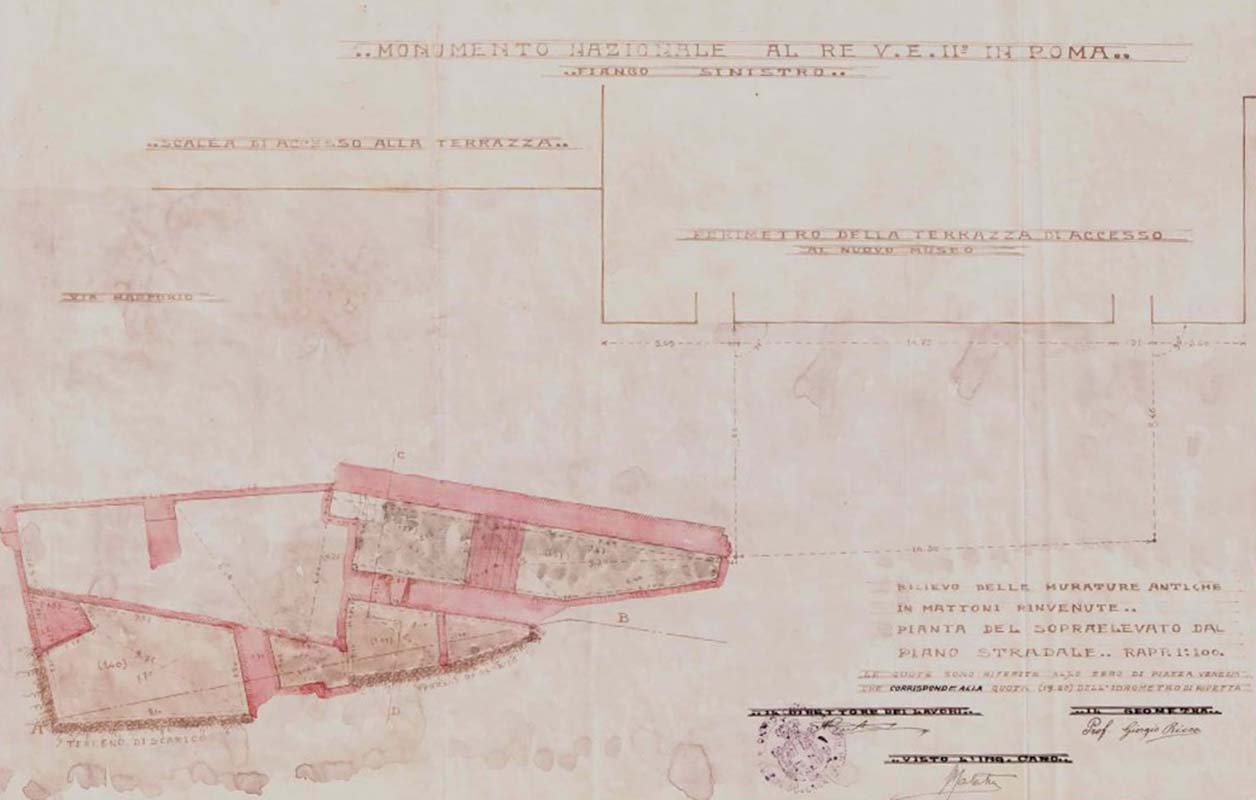

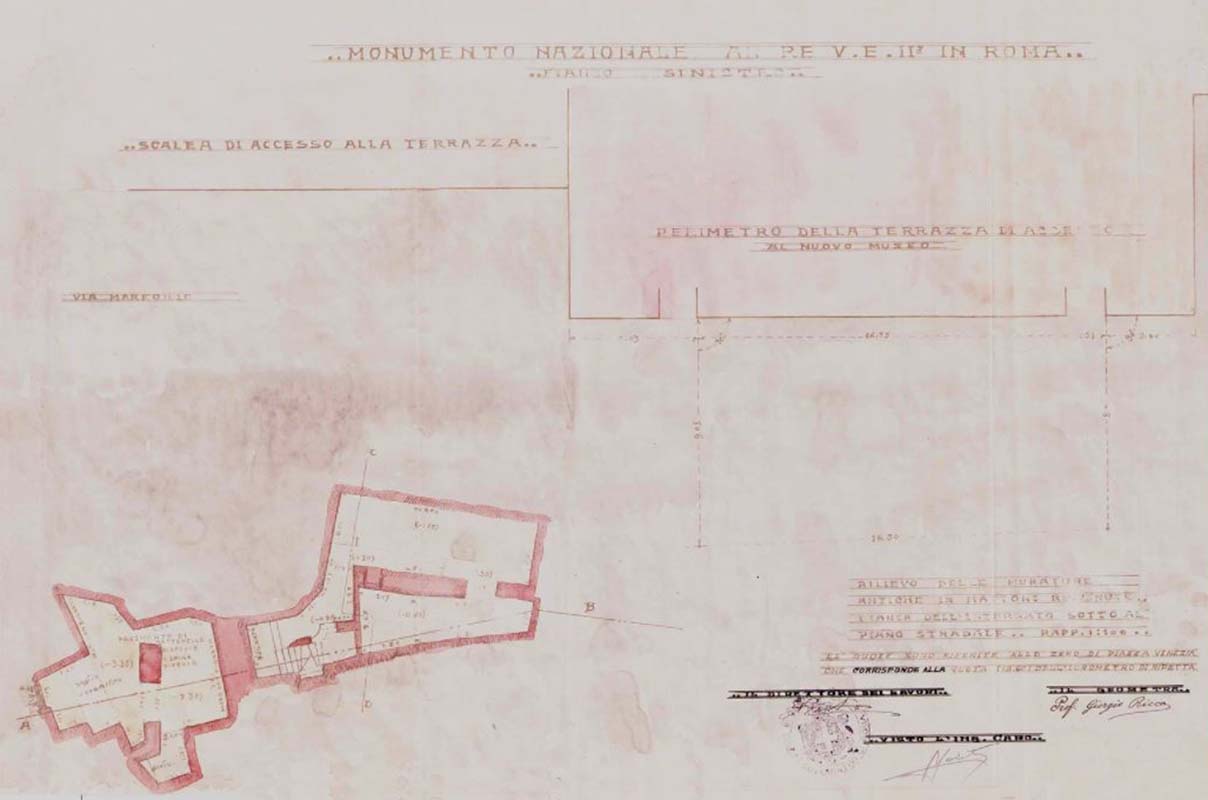

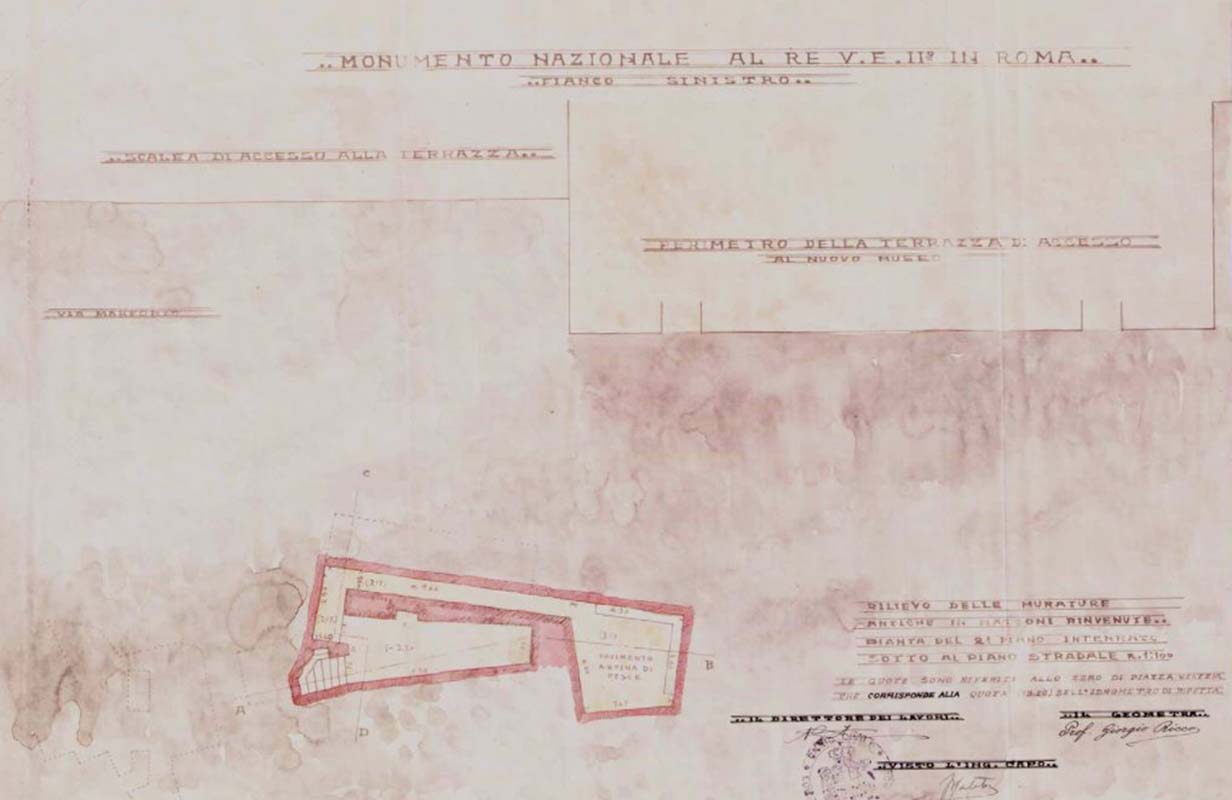

Album with watercolour-painted maps and elevations, containing the outlines of ruins on the Capitoline Hill and its surroundings discovered during the excavations for the construction of the new Museum of the Risorgimento, Works Engineering Office, also known as the Civil Engineering Dept.

At the same time, Sacconi moved towards a new iconography of the decorative apparatus. He abandoned the historical subjects which he had envisaged in the first project and turned more and more decisively towards allegories.

Giuseppe Sacconi e l'Opera sua Massima, by Primo Acciaresi, pub. 1911

In this context, Giuseppe Sacconi inserted an Altar of the Fatherland in the Vittoriano. The architect destined the central area of the Monument on the first terrace, below the statue of Victor Emanuel II on horseback, to a large votive altar dedicated to the Italian nation.

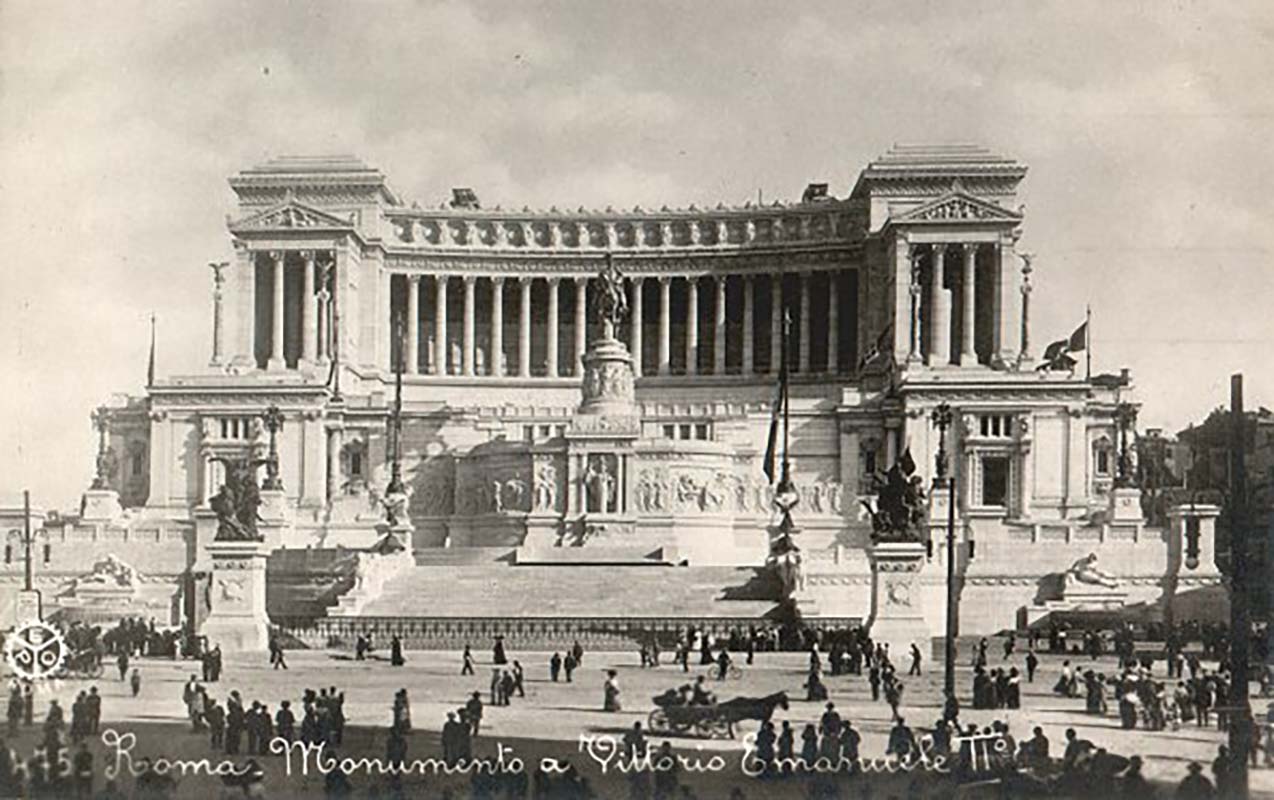

View of the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II (the Vittoriano) in the early 1920s

The central part of the Vittoriano: the Altar of the Fatherland with the lateral friezes and, at the centre, the goddess Rome, modelled after a sculpture by Angelo Zanelli, and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

The enlargement of the portico had led to an enlargement of the overall dimensions of the Vittoriano. In this new layout, the Monument was no longer fully visible to those arriving from Via del Corso. Sacconi therefore urgently felt the need to completely rethink the relationship with the area in front of it.

Construction of the Vittoriano under way with the expansion of the portico

View of the Vittoriano during its construction from the present-day Via del Corso: at right is the Palazzetto Venezia being demolished

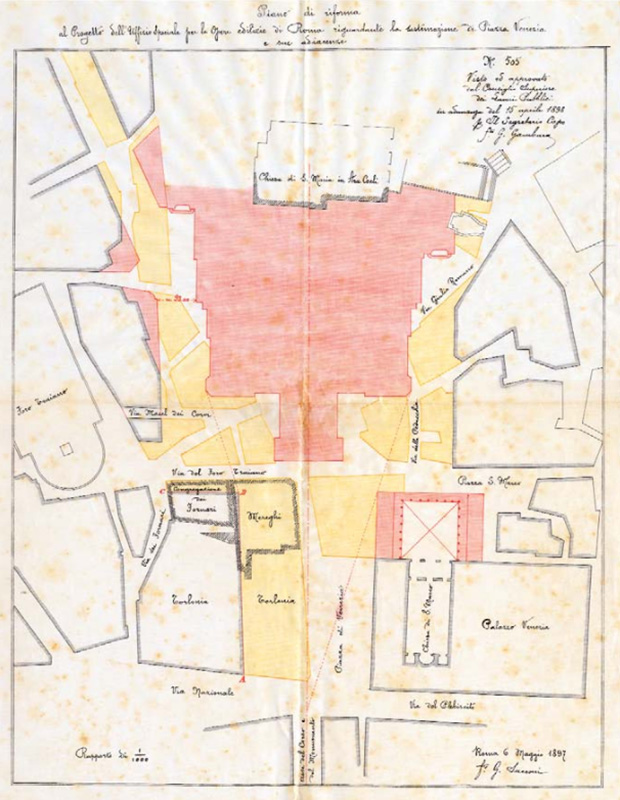

In 1897, Sacconi presented a complete project for Piazza Venezia, based on a rigidly symmetrical criterion: it involved moving the so-called Palazzetto di Piazza Venezia, the destruction of Palazzo Torlonia and the construction of a new building similar to Palazzo Venezia in a set back position.

Renovation Plan for Piazza Venezia and its surroundings, signed by Giuseppe Sacconi on 6 May 1897

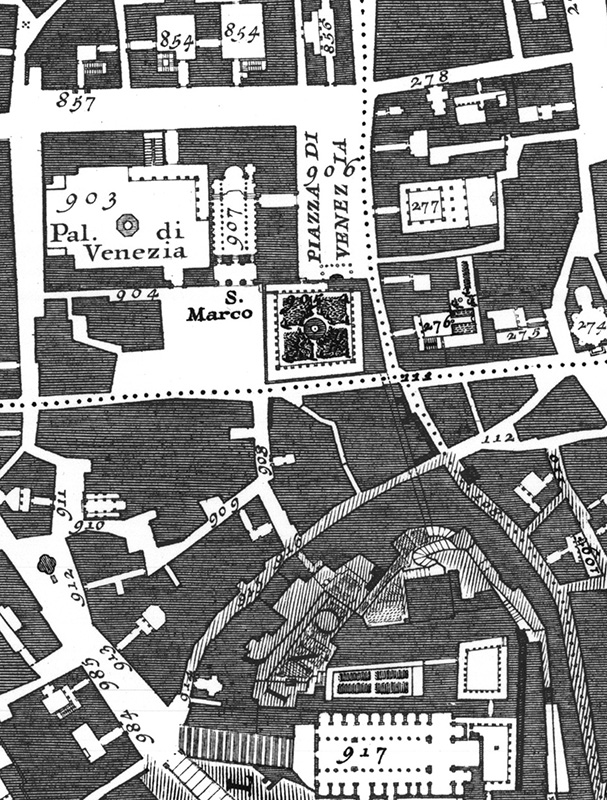

Piazza Venezia and its surroundings in Giovanni Battista Nolli's famed 1748 Map of Rome

Aerial view of Piazza Venezia and its surroundings with the Palazzetto Venezia at the bottom left and, in front, the demolished Palazzo Bolognetti-Torlonia, circa 1860

The Capitoline Hill seen from Piazza Venezia with the Palazzetto and, at right, the now-demolished Palazzo Bolognetti-Torlonia, circa 1860

View of Piazza Venezia, Hendrik Frans Van Lint, oil on canvas, 18th century, in the collection of the Museum of Palazzo Venezia. Shown from what is now Via del Corso, the Capitoline Hill is in the background and Palazzo Venezia can be seen on the lower right.

The Palazzetto as it was being moved

Piazza Venezia from the Vittoriano in the 1950s: construction in the area with Palazzo Venezia at left and the Assicurazioni Generali Building at right, which replaced the now-demolished Palazzo Bolognetti-Torlonia