During the First World War, the palace passed to the Kingdom of Italy. A new chapter then opens, in the name of the museum

On 24th May 1915, Italy entered the First World War, siding alongside England and France against Germany and Austria. Although several hundred kilometres away from the front, in its own fashion, Palazzo Venezia also became a place of contention. Until then, the Empire had maintained two distinct embassies in Rome. The one in Palazzo Chigi, previously rented by the self-same princes, was used by the Kingdom of Italy and had been closed the day after the declaration of war. The second in Palazzo Venezia housed the embassy to the Holy See and, precisely as such, continued to remain in operation for another eighteen months.

Entry portal of Palazzo Venezia on Via del Plebescito with the first steps of the stairway by the architect of the Austrian Embassy, Camillo Pistrucci, in 1911

In August 1916, with mounting frustration for the outcome of the conflict and anger at the Austrian bombing of the Serenissima, the Italian government decided to requisition the building from the enemy. The handover took place on 1st November of the same year. It was a mere bureaucratic act: at 14.00 pm sharp, as agreed, the Minister of Finance Filippo Meda, accompanied by a notary and two officials, knocked on the door of the building, to collect "the keys without opposition".

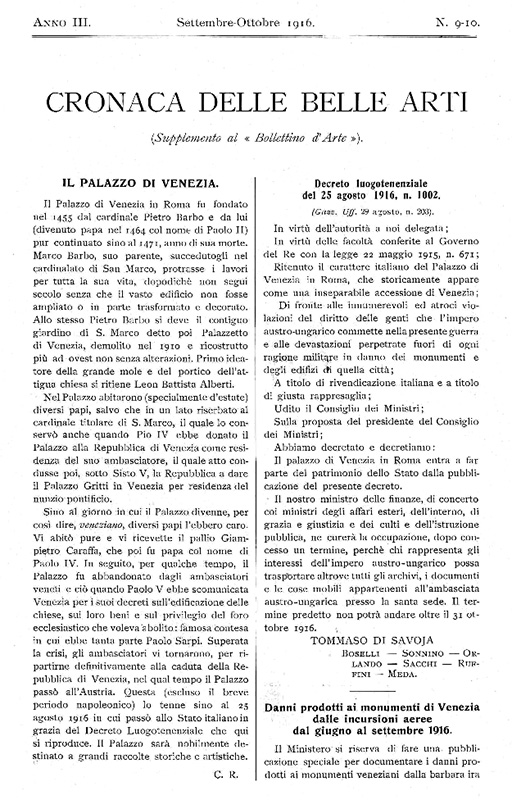

Lieutenant's Decree, n. 1002 of 25 August 1916 (Offical Gazzette n. 203 of 29 August), with which Palazzo Venezia in Rome became the property of the Italian State

The expropriation of Palazzo Venezia also became a diplomatic issue, not so much with the Austrian enemy, but with the Vatican, which naturally claimed the rights to this embassy. In order to soften the tone of the controversy, as early as 15th October, that is even before the handover, the Italian government published a decree that designated the building as a museum.

Letterhead of the National Museum of Palazzo Venezia, from a woodcut designed by Duilio Cambellotti in 1920 (circa)

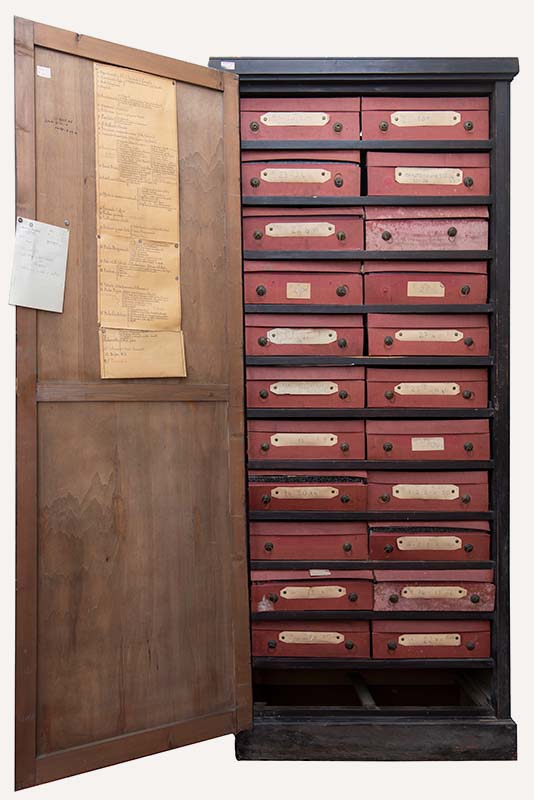

Palazzo Venezia. Manual of Existing Fabrics in the Warehouse of the Administration, in the collection of the Archive of the Museum of Palazzo Venezia

The official name, Museum of the Palazzo di Venezia, is due to art historian Corrado Ricci (1858-1934), at the time head of the Antiquities and Fine Arts General Directorate. Ricci had great confidence in the future of the new institute: "What must triumph for us - he wrote to the Minister of Education Francesco Ruffini - is the name of Palazzo Venezia and the public will need to say, “Let's go to the Palazzo di Venezia” just as it says 'Let's go to the Louvre...'".

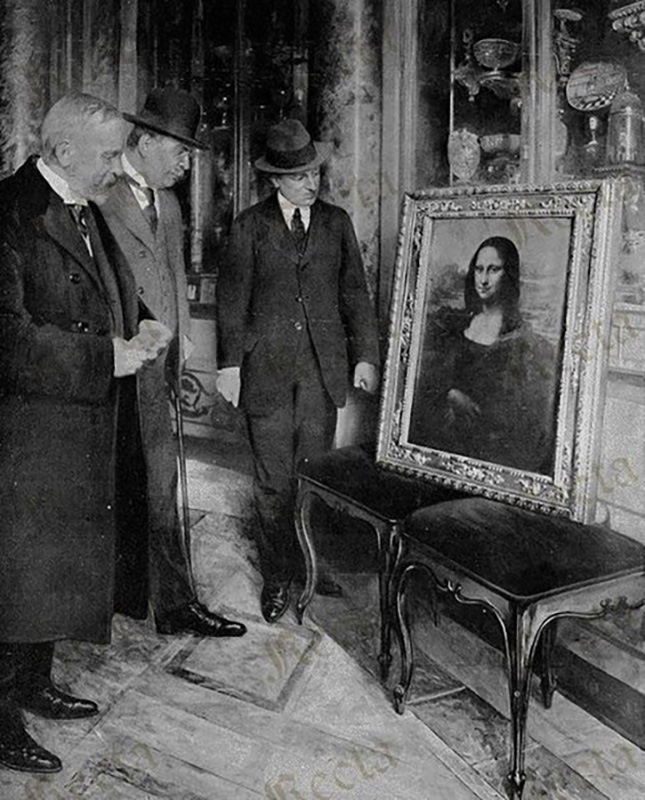

Corrado Ricci (centre) with painter and restorer Luigi Canevaghi (left) and art historian Giovanni Poggi (right), admiring the Mona Lisa at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, 1903

Housed in Palazzo Venezia, unanimously considered one of the clearest and most majestic expressions of the Italian Renaissance, the museum was born with great expectations. In line with its container, the idea arose of making it the Museum of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The position of first director fell to art historian Federico Hermanin (1868-1953), as superintendent of the Galleries and Museums of Lazio and the Abruzzi.

Federico Hermanin in his studio in Palazzo Venezia, circa 1920

Already the following year, 1917, Hermanin, assisted by Corrado Ricci, was able to develop an exhibition project, according to which the museum should take on the features of a noble residence of the sixteenth century.

Armoire containing the Hermanin Archive, now part of the collection of the Archive of the Museum of Palazzo Venezia

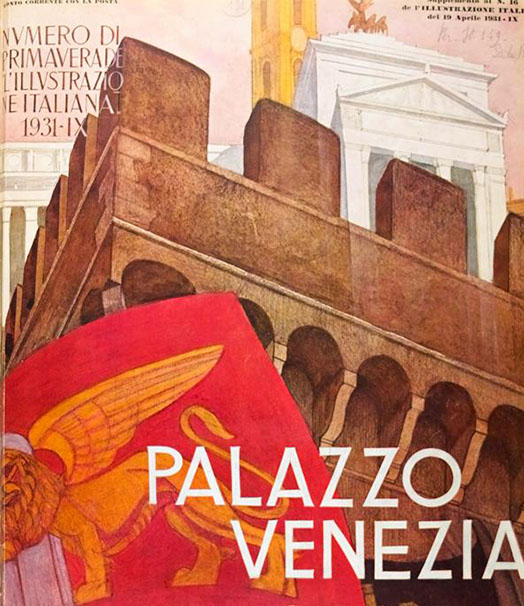

Palazzo Venezia, edited by Federico Hermanin, in the illustration by Vittorio Grassi from L'Illustrazione Italiana, supplement to n. 16, 19 April 1931

At that stage, the conditions of the building appeared to be critical. Over the centuries, several rooms had undergone profound tampering, which had compromised their original structures and spatiality. Just think that the Sala del Mappamondo and the Sala Regia, in addition to having been fragmented into various rooms, were simply devoid of ceilings and floors. Hermanin did a remarkable job. After demolishing the partitions, the director conducted the first research on the ancient walls: fragments of frescoes from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries emerged, which he attributed respectively to Mantegna and Bramante.

Sala del Mappamondo (Hall of Maps) prior to restoration, detail of a wall with fragments of a 15th-century fresco, in a watercolour by Ada Levi from 1919

Sala del Mappamondo prior to restoration, detail of a wall with fragments of 15th-century and neoclassical frescos, in a watercolour by Ada Levi from 1919

Sala del Mappamondo (Hall of Maps) with the recreation of the original wall decoration featuring the crest of Innocent VIII in a watercolour by Ada Levi from 1917-1920

Sala del Mappamondo (Hall of Maps) with the restoration of the original decoration on one wall, in a watercolour by Alfredo Energici and Enrico Ruffini from 1917-1920

At the same time, works were selected from the deposits and exhibition rooms of the other Capitoline museums, to be sent to Palazzo Venezia. As well as towards Castel Sant'Angelo, Hermanin turned his gaze towards the National Gallery of Ancient Art, at the time located in Palazzo Corsini: his attention fell on the pieces coming from the Monte di Pietà and on those left by Henrietta Hertz (1846-1913) at her death in 1913.

Portrait of Henrietta Hertz

Head of Nike, also called the Hertz Head, in the collection of the Museum of Palazzo Venezia

Lute Player, Andrea Solario, oil on canvas, originally part of the donation made by Hertz and kept at the Museum of Palazzo Venezia, today it is part of the collection of the National Gallery of Ancient Art at Palazzo Barberini

The museum project therefore took shape, albeit amid growing difficulties. The main one is to be found in the setbacks suffered by the Italian army in the summer-autumn of 1917. In the weeks following the defeat of Caporetto, which took place on 24th October, the building took on the role of an emergency shelter for works of art arriving from the cities that were most vulnerable to the Austrian troops, starting with Venice. Hence the temporary presence in the palace of masterpieces transferred in haste from the Serenissima, such as the bronze quadriga of San Marco and the equestrian Monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni by Verrocchio, documented by period photographs.

The horses of the Quadriga of Saint Mark’s Basilica (Venice) arriving at Palazzo Venezia in Rome during WWI

The horses of the San Marco Quadriga in the large courtyard of Palazzo Venezia in Rome during WWI

The equestrian monument of Bartolomeo Colleoni by Andrea Verrocchio in Palazzo Venezia in Rome during WWI

The situation took a decisive turn in the autumn of 1918 with the triumph of Vittorio Veneto and the subsequent surrender of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In this new and different dimension, Palazzo Venezia, taken away from Vienna, became one of the symbols of the victorious tricolour. The museum inside travelled on the wings of this patriotic enthusiasm. In 1919, director Federico Hermanin offered a preview, setting up a selection of the works which had converged into the collections in some rooms of the Cybo Apartment. The goal was to persuade citizens that "the glorious Palace is intended to house a museum of painting, sculpture and minor arts".

Federico Hermanin's 1919 decoration of the first room of the Barbo Apartments

In June 1921, the support of Benedetto Croce (1866-1952), then Minister of Education, allowed opening the first rooms of the museum, located inside the Barbo Apartment. However, that set-up was short-lived. After just one year, Hermanin was forced to vacate the Barbo rooms to make way for the exhibition of the works that Austria had had to return to Italy. The exhibition, marked by the tones of an increasingly accentuated nationalism, opened its doors in December 1922: with an installation designed by Armando Brasini (1879-1965), one of the enthusiastic spectators was Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), who a few weeks earlier, had taken over the reins of the government.

View of the Sala delle Battaglie (Hall of Battles), previously the Sala del Concistoro (Hall of the Council) in 1922-1923 with the exhibition of the historical-artistic items that returned to Italy from Austria after WWI

The Sala delle Battaglie (Hall of Battles), previously the Sala del Concistoro (Hall of the Council) as decorated by painter Giovanni Costantini according to a design by architect Armando Brasini in 1928-1930