In the aftermath of the conflict, Palazzo Venezia once again plunges into art: a series of exhibitions, the museum and the resettlement of the heritage protection offices mark a new path, which definitively distances it from active diplomacy and politics

One of the themes that marked the last phases of the Second World War consisted in saving the main Italian works of art from German raids. Aldo De Rinaldis (1882-1949) and even more so Emilio Lavagnino (1898-1963), are among those art historians who made every effort in this direction, sometimes risking their lives. Both one and the other pivoted on Palazzo Venezia. Among other things, Superintendent De Rinaldis organised the exhibition Masterpieces of European painting: open from 28 August 1944 to 18 February 1945 in the Barbo Apartment and commissioned by the allied military government, the exhibition featured precisely the works that had been stored in Rome and the Vatican during the preceding months.

Portrait of Aldo De Rinaldis painted by Lucia Tarditi, now at the Borghese Gallery in Rome

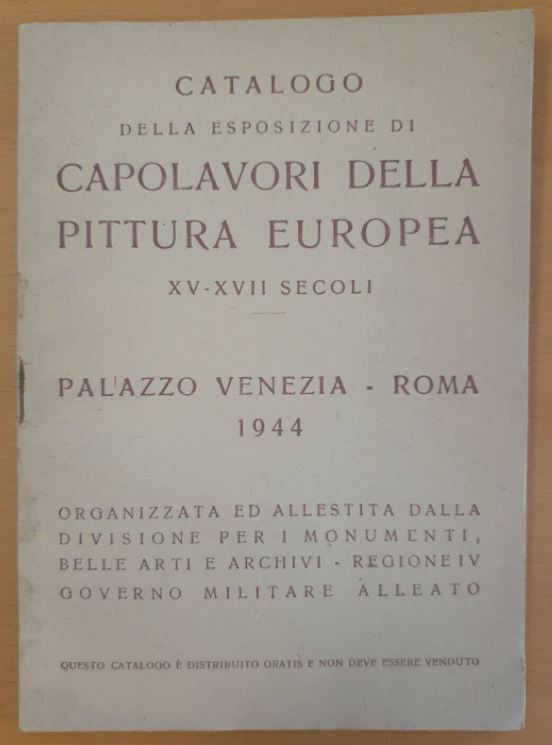

Catalogue for the exhibition titled Masterpieces of European Painting. 15th-17th Centuries, held in 1944-1945 and organised by the Monuments, Fine Art and Archives Office - Region IV of the Allied Military Government

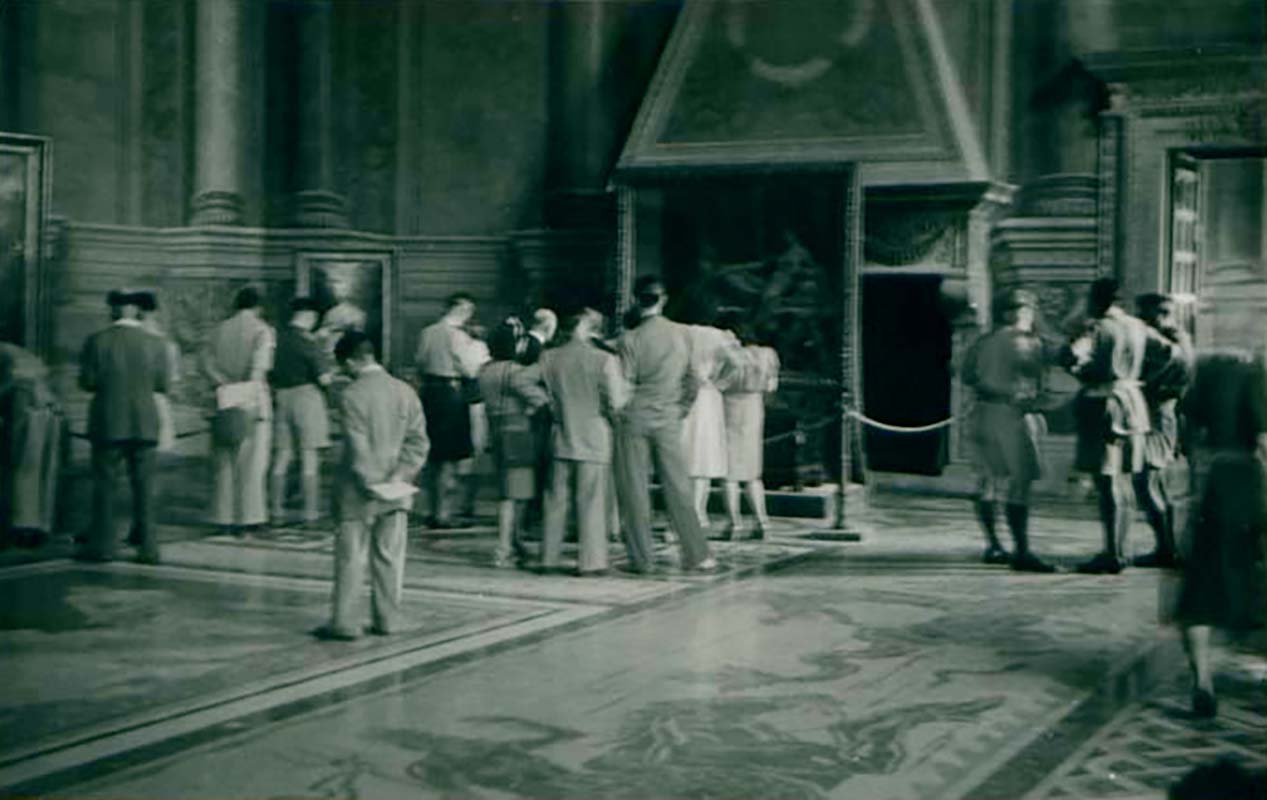

The Sala del Mappamondo (Hall of Maps) during the Masterpieces of European Painting exhibition, 1944-1945

As for Lavagnino, superintendent inspector and then director of the National Gallery of Ancient Art, he had taken on the responsibility of transferring hundreds of masterpieces from all over Italy to the Vatican, many of which had in fact passed through the halls of Palazzo Venezia. That’s not all. The founder with another staunch anti-fascist, Umberto Zanotti Bianco, of the National Association for the Restoration of War-Damaged Italian Monuments already in 1944, in 1945 Lavagnino also organised the Italian Art Exhibition at Palazzo Venezia: the initiative, the first of its kind to be conceived and set up by Italians, helped to recognise the artistic heritage as one of the main tools for rebuilding a new and democratic relationship between the culture and society of the Country, disrupted by the fascist regime and the war.

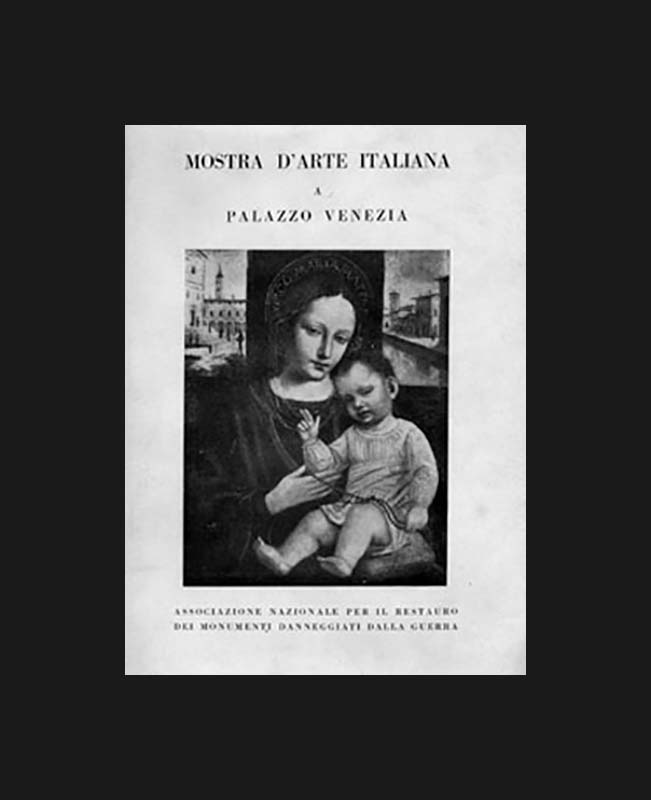

Catalogue from the Italian Art exhibition of 1945, organised by the National Association for the Restoration of Monuments Damaged in the War

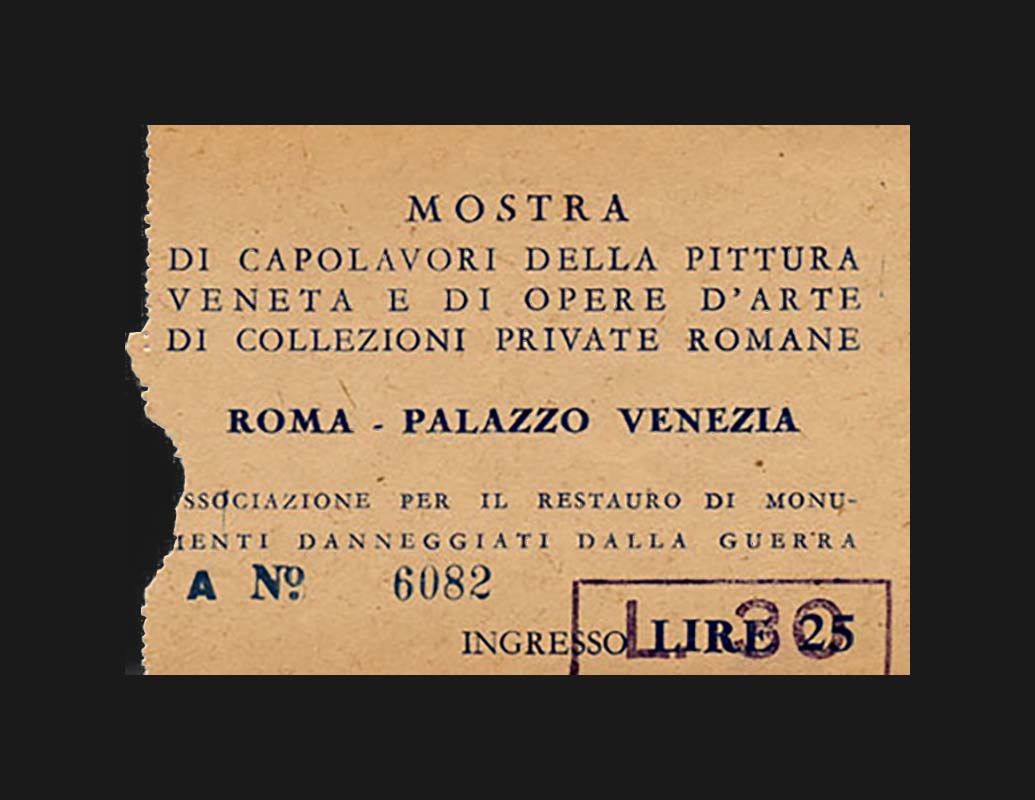

Admission ticket to the Italian Art exhibition of 1945, which included numerous Venetian Renaissance masterpieces and, in the second section, privately-owned pieces from every era and geographical region, on loan from some of Rome’s most important collections

But why Palazzo Venezia? Both De Rinaldis and Lavagnino intentionally established a bridge with the now historic exhibition of art objects returned from Austria-Hungary in the post-war period, to give back to the community a heritage of art, history and culture that had been removed by a double tyrannical power, the fascist regime and the German army, for too long. Certainly not by chance, the exhibitions were held in the Barbo Apartment, the place that Benito Mussolini had taken possession of at the time.

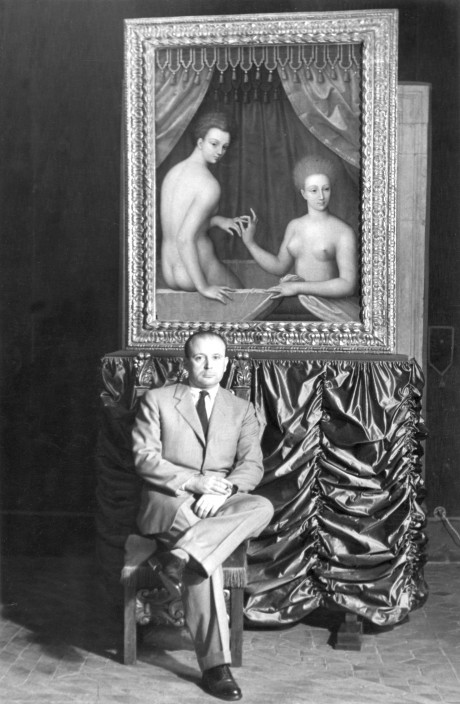

Rodolfo Siviero, art historian and secret agent, posing in front of a restored late-16th-century School of Fontainebleau painting in a room in Palazzo Venezia during the Second National Exhibition of Artwork Returned from Germany, 1951

The 1944 and 1945 exhibitions paved the way for reopening the Palazzo Venezia Museum to the public, an act which took place in the same 1945 on the main floor. The responsibility fell to the new director, Antonino Santangelo (1904-1965). During the years that followed, Santangelo worked hard to expand the collections, among other things by taking possession of the collection of Gennaro Evangelista Gorga, known as Evan (1865-1957).

The collection of terracotta pottery once owned by Evan Gorga in his apartment in Via Cola di Rienzo, Rome

Gorga, an internationally renowned tenor, was also known as a voracious collector of art and even more so of musical instruments. He had offered a taste of it in 1911, when, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the unification of Italy, over a thousand pieces were temporarily exhibited in Castel Sant’Angelo, capturing the attention and greed of the banker John Pierpont Morgan. The ministerial convention for keeping the Gorga works in Italy is dated 27th November 1949. The following year, 1950, a substantial part was transferred to Palazzo Venezia.

Achilles Dragging the Body of Hector, a terracotta sculpture by Bartolomeo Pinelli (1833) from the Gorga collection, now kept in the storerooms of the Museum of Rome - Palazzo Braschi

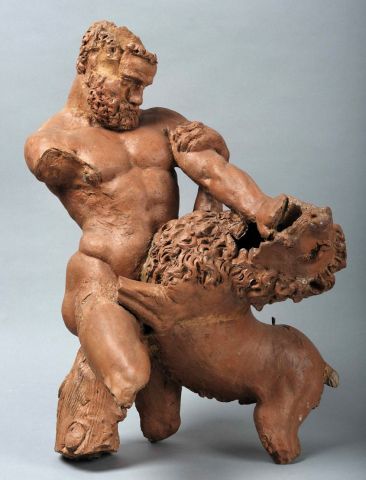

Hercules and the Nemean Lion, terracotta, Bartolomeo Bandinelli (Baccio Bandinelli), circa 1530-1540, from the Gorga collection, now part of the collection of the Museum of Palazzo Venezia

In the early fifties, the collections housed inside Palazzo Venezia took on a decisive slant towards applied arts, or decorative arts. The decision was certainly affected by the purchase of Palazzo Barberini in 1949 and by the decision to make it the second seat of the National Gallery of Ancient Art. By 1953, many paintings already in Palazzo Venezia were moved to Palazzo Barberini, including several from the Henrietta Hertz collection.

Plaque from the Industrial Arts Museum (MAI - Museo Artistico Industriale)

Room V of the Industrial Arts Museum (MAI - Museo Artistico Industriale) in the Via Conte Verde location, as decorated by Luigi Serra in 1934

Within this framework, Palazzo Venezia was assigned pieces that had once belonged to the Industrial Art Museum, or MAI. The MAI, linked to the initiative of Prince Baldassarre Odescalchi (1844-1909), was born in 1874, with the aim of following in the footsteps of the South Kensington Museum in London, today's Victoria & Albert Museum, but in the end, it never really took off. Among the many MAI objects that can still be appreciated today in Palazzo Venezia, it is worth noting at least the four reliefs with the Stories of St. Jerome by Mino da Fiesole.

Four bas reliefs depicting the Stories of St. Jerome by Mino da Fiesole

The particular direction assumed by the museum continued in 1959, with the purchase of the collection of Prince Ladislao Odescalchi (1846-1923). Like his brother Baldassarre, Ladislao had been one of the protagonists of artistic fin de siècle Rome, distinguishing himself for his interests in art and even more so in the weapons of all times and all countries. To put together his collection, he turned to antique dealers and collectors from all over Europe.

Display in the Odescalchi armoury as curated by Nolfo di Carpegna, in the Sala del Concistoro (Hall of the Council), Palazzo Venezia

The so-called Odescalchi Armoury, which at the death of Ladislao was transferred to his nephew Innocenzo and reorganised in the ancestral palace of the Santi Apostoli, in 1953 numbered two thousand among firearms and blades, both offensive and defensive. About eight hundred were transferred to the Castle of Bracciano, where they are still housed today; as for the remaining twelve hundred, they were acquired by the Italian State, destined for Palazzo Venezia. In 1969, at the time of the directorship of Maria Vittoria Brugnoli (1915-2013), the weapons found temporary accommodation in the monumental rooms, through an installation whose scientific aspect was curated by Nolfo di Carpegna (1913-1996).

Infantry commander's armour by Michael Witz the Younger, 1550-1560, Museum of Palazzo Venezia

On June 23, 1982, the Garibaldi exhibition was inaugurated. Art and History: the exhibition was organised in two sections, one on history at the Central Museum of the Risorgimento, the other, on art, in the monumental rooms of Palazzo Venezia. Over the years the palace had continued to host temporary exhibitions, often adapting to the direction towards applied arts taken on in the meantime by its museum. These included French tapestries from the Middle Ages to today in 1953, the National historical exhibition of miniatures in 1959, curated respectively by Georges Fontaine and Giovanni Muzzioli, or, again, the Exhibition of Drawings from the English Royal Collections at Windsor in 1961.

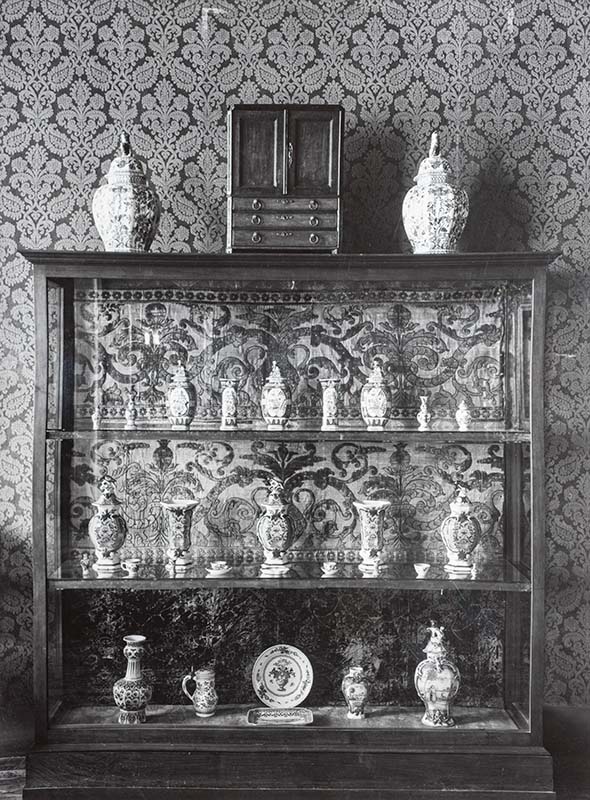

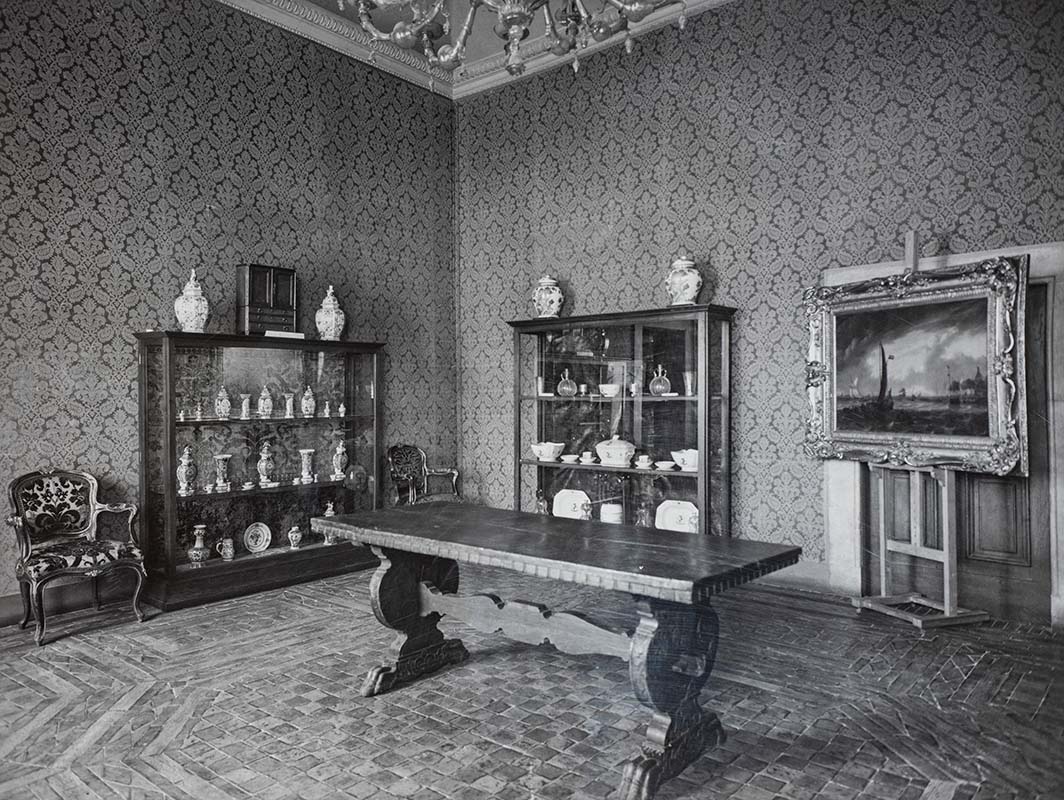

Display of the Antique Dutch Pottery exhibition, 1949

Display of the Medieval Yugoslavian Frescoes exhibition in the Sala del Mappamondo (Hall of Maps), Palazzo Venezia, 1950s

Exhibition of sculpture from the American Academy in Rome, British School at Rome and Swiss Institute in Rome at Palazzo Venezia, 1950

Cover of the catalogue of the National Exhibition of Miniatures, 1959

However, presented itself in a different way, effectively opening a new era. In a climate of growing interest towards cultural heritage, the commissioner of the exhibition, the art historian Sandra Pinto (1939-2020), interpreted the building as a suitable venue for events of national and international resonance, capable of keeping together scientific quality and high dissemination. The path trodden by the Roman art historian was followed by Gianfranco Spagnesi with The colour of the city in 1988, Dante Bernini with Caravaggio: new reflections in 1989, which were followed by monographic events dedicated, among others, to Pietro da Cortona, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Caravaggio and Sebastiano del Piombo, the first curated by Anna Lo Bianco, the remaining three by Claudio Strinati.

Cover from the catalogue of the show titled Garibaldi. Arte e Storia (Garibaldi: Art and History), 1982

Cover of the Caravaggio: New Reflections exhibition, 1989

Cover of the Pietro da Cortona 1597-1669 exhibition in 1997

To make room for Garibaldi, Art and history the organisers dismantled a substantial part of the museum's permanent exhibition, including the Odescalchi Armoury. The operation, which at the beginning was to be temporary, also because of the success of that exhibition, would characterise the future structure of both the Barbo Apartment and of the monumental rooms, still without furnishings. De facto, the path of setting up large exhibitions, whose occasional visitors made this worthwhile, involved confining the Palazzo Venezia museum between the Cybo Apartment and the second floor of the Palazzetto.

Museum display curated by Paola Della Pergola, formerly the Director of the Borghese Gallery, Rome, in 1979-1980

The museum of Palazzo Venezia therefore appeared marked in the following period by a series of specific interventions, united by the desire to enhance the individual collections. In 1983 it was decided to divide the objects into categories: hence, one after the other, we have paintings, majolica, bronzes, terracotta and so on, lined up. This course, which took up once again the direction on applied arts taken on during the fifties, was reflected in the exhibition set up by Franco Minissi (1919-1996) in the late eighties.

Museum display of the Medieval art section curated by architect Eugenia Cuore, 1985

Museum display curated by architect Franco Minissi, 1988

In July 2006, Maria Giulia Barberini inaugurated the Lapidarium of the Museum. Over time, several hundred works in marble or other stones had converged to Palazzo Venezia, ranging from the classical age to the seventeenth century. Some had come to light in the early twentieth century, during the excavations for the foundations of the new Palazzetto, others came from the Industrial Art Museum or from the Palazzo Mattei collection. The Lapidarium was set up outside the second floor of the Palazzetto, overlooking the enchanting orange courtyard.